A teach-in about the War on Workers took place recently in Washington, DC.

“The war”’ was described and analyzed by four panelists and a moderator. The moderator was male. Three of the panelists were males. The one woman came from the National Education Association. The panel discussed at some length the state of union activities in the U.S. given the struggles in Wisconsin and other areas of the country. Then the panel took questions.

I asked about gender politics, about the relation between the attacks on the funding of women’s resources, such as reproductive health, the general attack on collective bargaining rights from the State, and what labor unions were doing about it. When Scott Walker and friends decided to eliminate collective bargaining rights from Wisconsin’s public sector workers, they only did it to female-dominated fields like teachers and nurses, but not to male-dominated ones like police and firefighters.

The panel did not answer my question. But all four men did look to their right at the woman at the end of the table. One of them then said, in a loud voice, “Ladies first!”

The response from the NEA representative was that women’s rights were something that unions had fought for as part of the broader labor movement, and that these attacks from the right were typical reactionary nonsense. There was no discussion on what labor unions were doing to address this intersection between gender and the labor movement.

Needless to say, this response did not satisfy me. But then I realized—the panel had relayed the philosophy that haunts women in the workforce, from the local to the global, from unions to the State: Ladies first!

Politicians can’t use the necessary vocabulary when discussing reproductive health, but a congressman can viciously tell lies about Planned Parenthood and alter records to get away with it. The House of Representatives tried with all of its might to redefine the definition of rape to include a stipulation of whether the act is “forcible” or not, all for the sake of denying women access to safe abortions. In the words of Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz, the proposed bill was “a violent act against women.” Meanwhile, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia claimed that the Constitution does not grant the same protections to women or the LGBTQ community as it does to other groups.

What is the logic behind who should be eliminated from the State’s dialogue, whether it’s in debate or in established law? Ladies first!

New Jersey Governor Chris Christie is the poster-child for attacking teachers’ unions, whether he is stumping or berating individual teachers. The rhetoric involves insults and putting dissenters “in their place,” as well as comments that sexualize State actions against teachers’ unions. In the same period, Christie told the press to “take the bat out” against a female state senator, prompting two other women politicians from New Jersey to criticize his comments as advocating violence against women. Earlier in the same year, Christie vetoed a bill that would have provided funding for women’s health and family planning through an expansion of Medicaid programs because of New Jersey’s budget crisis. Christie has blamed this budget crisis on teachers’ unions as a scapegoat to pass austerity measures, even though his administration “forgot” to apply for federal educational funding.

In Wisconsin, Scott Walker’s administration’s attempt to take away collective bargaining rights from public-sector workers has targeted women workers. Other austerity measures being debated cut funding from women’s reproductive health services. All of this austerity against women is in the service of a budget crisis that isn’t even real.

When the austerity State decides to cut funding for social services and get rid of basic workplace rights, which population does it look to? Ladies first!

After the panel was over, the one woman panelist came up to me and said that although many high-ranking officials of the NEA are women, she and others in the organization never thought of the attacks on collective bargaining as a “women’s issue.” Often women’s rights in reproductive health and in the workplace are painted as two separate issues, but they are not.

The panel’s response reproduced the same narrative. And this narrative of women as secondary to the “movement” as a whole, brings up a final question:

When a progressive movement needs to react to the State’s austerity measures, what representation is conveniently forgotten in the overall narrative?

“Ladies first!”

It’s time to move beyond the chivalrous, neoliberal logics of “Ladies first!” and talk about, teach, and organize for all workers’ power and rights, equally and at the same time.

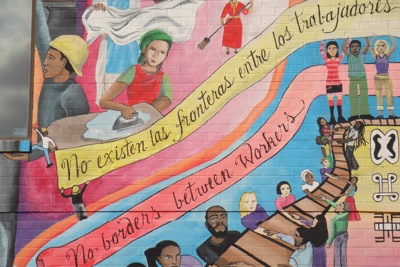

(Photo Credit: Workers World)