Domestic labor, which includes everything from caring for the elderly to doing laundry, is a profession that exists globally. From South Africa to China to England, domestic labor exists in hundreds of thousands of households. A great deal can be learned from researching the pivotal group of domestic laborers across cultures. Domestic labor is important.

Something is important when it has great value or significance. In the case of domestic work, it means that it is worth it to take the time and energy to examine and understand the purpose, consequences, and meaning of domestic care and labor. Domestic work is important because it changes society. Domestic labor or care is an integral and important element of global society. Examining the importance of this labor form allows for a greater understanding of that global society. Through a closer examination of domestic labor, or by considering it to be significant, more can be learned about class, race, gender, cross-cultural interactions, and global exchange.

In the United States, a “care crisis” is currently plaguing families as the ageing baby boomer population heads into retirement. The crisis consists of more elderly persons needing some type of care and fewer able to provide it. Because of improvement in health care that extend a person’s lifespan, the demand for these works is likely to increase and become a serious problem. The “care crisis” cannot be managed by dealing with the number of individuals that require care. Instead, we must consider the workforce and look at how appropriate care workers can be introduced into the workforce. Caring Across Generations attempts to address this issue by finding solutions to the care crisis through training programs, policy solutions, and enhancing the relationships between care workers and those they care for. This “care crisis” is an important issue in American society today. By understanding and studying the field of care work, we can better understand and find ways to fix, manage and survive the crisis.

Part of the problem is the value of work: “It is easy to appreciate why work is held in such high esteem, but considerably less obvious why it seems to be valued more than other pastimes and practices”. Work is acknowledged as something important, and choosing to not work results in condemnation. But only specific types of work hold value. For example, there is a great difference between the work of a neurosurgeon and a janitor. It is said the former required years of education, training, and work to be able to attain his or her position. The janitor required less training and preparation to be perform her or his labor correctly. So, the janitor is paid much less than the doctor. But is the janitor’s work less valuable?

According to US standards, yes, it is. The work performed by the janitor is considered commonplace, and she or he is considered replaceable. The wages for housework is a perfect large-scale example. Housewives asking for compensation for work they were expected to perform with smiles on their faces seemed farfetched and unreasonable. Despite its budgetary difficulties, the plan had the potential to place the issue of housework on the national front burner.

The amount of work contributed through caring for children, the elderly, and maintaining a household should not be overlooked. It is a time consuming endeavor and an extremely important one. In this context, importance is so great that were the work to cease, society would collapse.

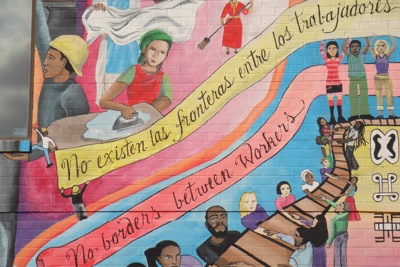

From the need for domestic workers to what the position itself can explain about social structures, domestic labor needs to be studied and understood. It is important. It deserves to be examined, researched, argued, debated, and challenged. A system of gender biases, abuse, and blatantly inhumane treatment persists in domestic labor employment. This is intolerable. Unless the field is examined, how can these systemic abuses be successfully eliminated and the contradictions of importance and value resolved?

Organizations such as the ILO are attempting to remedy the very real issues in this particular labor market, but it is a difficult road. The ills that exist within domestic labor are so ingrained that it seems nearly impossible to eradicate them completely. This, however, should not diminish the importance of domestic work. Just as poorly treated worker should not accept abuse because of fear, others should not accept silence merely because the task of change seems insurmountable. Change is slow and difficult, but it is necessary. And above all it is important.

(Image Credit: International Labour Organization)