The Green Wave, Bogota, February 2022

Welcome to March 2022, International Women’s Month; welcome to March 8, International Women’s Day; welcome to … the Thunderdome where, amidst all the recognition and all the ceremonies honoring women’s accomplishments and very being, one government, Nigeria’s, rejects Constitutional amendments designed to begin the process of gender parity, equity, equality. Another country, South Korea, elects a new President largely because he’s not only misogynist but explicitly anti-feminist. In a third country, Guatemala, on March 8, the legislature passed a law which extended the prison term for terminating a pregnancy from three to ten years, banned the teaching of sexual diversity, and, for good measure, in the name of the “protection of life and family”, banned same-sex marriages. So, basically, we’re not in Kansas anymore. We’re in Texas. Welcome to the Thunderdome.

On Sunday, the newly elected President of South Korea reiterated his determination to eliminate the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. He argued, first, that the work of the ministry had been completed. There was complete and total gender equality in South Korea. No matter that employment numbers, prior to the pandemic and even more, paint a different picture. No matter that violence against women and non-binary people is on the rise. What really matters is that `feminists’ have gone too far, and that’s the reason the new President is shutting the machinery, such as it is, down. It’s also a reason he was elected. He campaigned explicitly as an anti-feminist, who argued that gender based quotas stand in the way of “national unity”; that feminism caused South Korea’s low birth rate; that women falsely report sexual violence, and they must be punished, severely. Exit polls suggest that men in their 20s and 30s voted overwhelmingly for the anti-feminist.

These are grim times. But they are not without hope. There is light, there is real and serious opposition in the Thunderdome.

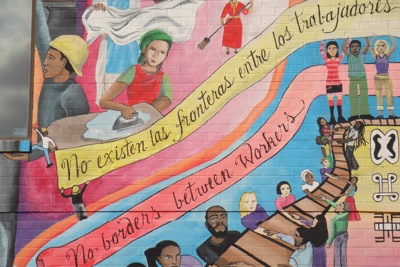

February ended with a landmark decision in Colombia decriminalizing abortion and setting the stage for the government to go further to codify and secure women’s access to reproductive health services as well as to dignity and autonomy. This victory in court was the product of numerous women’s organizations and movements doing the arduous, and joyful, work of reaching out and reaching in, of engaging with all parts of the society, with demanding while also educating while also learning. This is part of the great Green Wave that is surging across Latin America. It is also part of the electoral politics of Colombia, and so it is worth noting that in yesterday’s primary elections, leftist candidate Gustavo Petro has taken a resounding lead. The elections are in May. Further, on March 8, the Congress of Sinaloa, a state in northwest Mexico, decriminalized abortion.

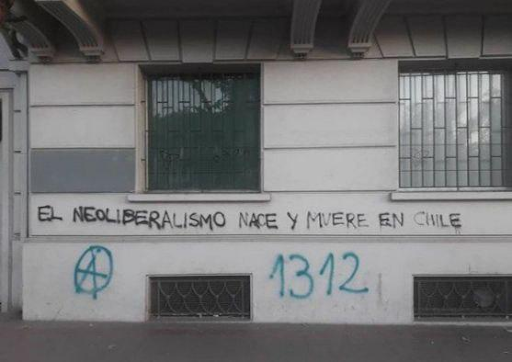

And speaking of elections, in December, Chile elected 36-year-old, leftist, pro-feminist Gabriel Boric to be President of Chile. Boric is the youngest person to ever hold that position. Perhaps more importantly, he won with the largest majority ever recorded in a Chilean election. On Friday, March 11, Gabriel Boric was sworn in. He stood with his progressive, majority-women Cabinet by his side. Bread and roses, words and deeds. Hope springs in the place that served as the proving ground for neoliberal devastation, and not only for Chile, for all of Latin America and beyond. Even now, even here, there is hope and optimism, being found, being made.

Chile

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit 1: Nathalia Angarita / New York Times) (Photo Credit 2: Carolina Pérez Dattari / Open Democracy)