“If we are serious about housing affordability for wage earners, we must understand that the market alone will not deliver it.” Patrick Condon

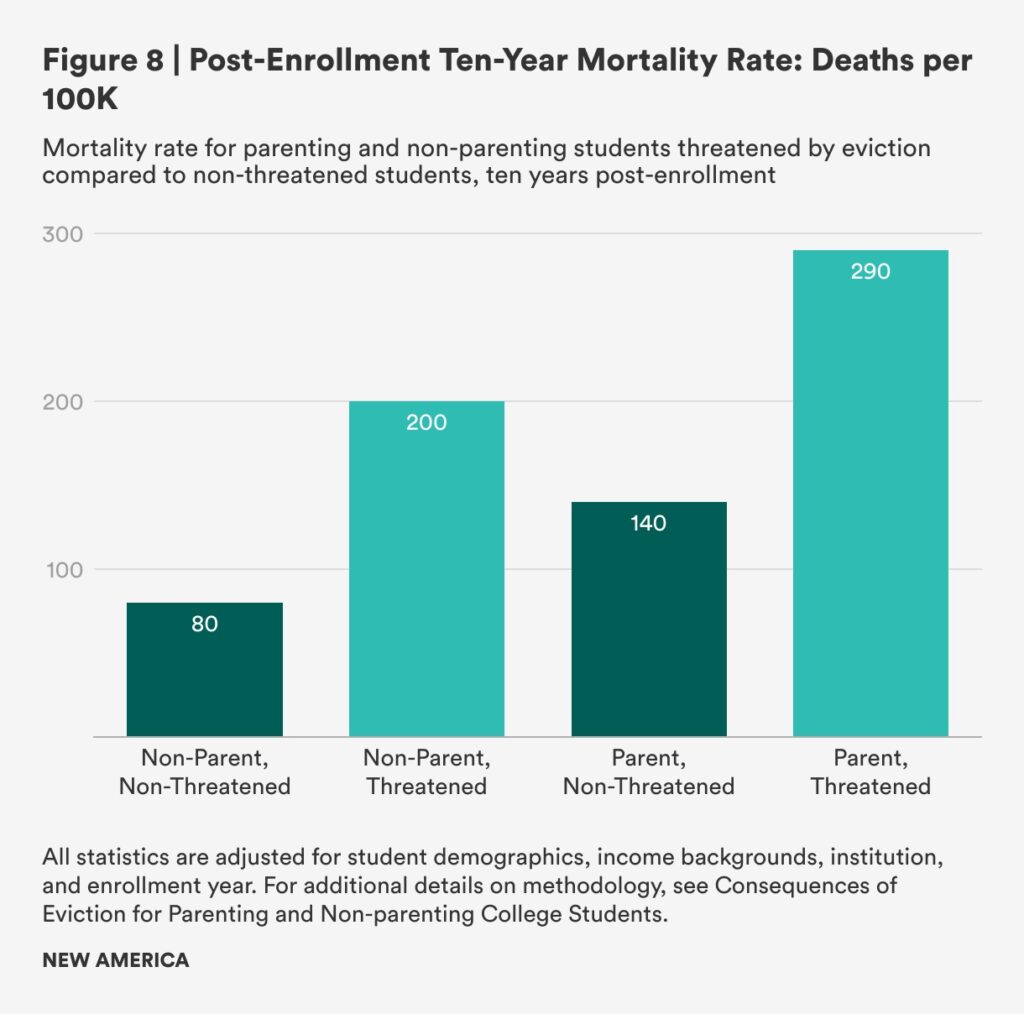

On October 27, England (but not Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) officially enacted the long-awaited Renters’ Rights Act: “Central to the Act is its provision to abolish Section 21 ‘no fault’ evictions, under which private landlords have been able to remove tenants even if they have done nothing wrong.” Between July 2024 and June 2025, 11,400 households suffered Section 21 no fault evictions. There is no count of how many people found themselves homeless as a result. As happens so often, the term “households” conceals as much as it reveals, but suffice it so say, tens of thousands of people were given two months to find a place, people who had done nothing wrong and now faced homelessness. Again, “homelessness” covers as much as it conceals. Numbers exist for those in shelters or seeking assistance. No one knows how many moved in with family or friends … “temporarily”.

While the Renters’ Rights Act is a welcome change, and not only because of the abolition of Section 21, some must wonder why it took so much to eliminate no-fault eviction, and why it takes so much to do so in other countries, such as the United States? No fault eviction was always wrong, always a violation of people’s human dignity and human and civil rights, but in a climate in which living on the streets has itself become criminalized, it’s even worse.

The Renters’ Rights Act does more than abolish Section 21. It also bans landlords from refusing tenants that receive benefits or that have children and establishes a new Private Rented Sector Landlord Ombudsman, where renters will be able to register complaints about landlords. Furthermore, landlords will not be able to raise the rent above the “market rate”. Landlords will not be allowed to allegedly respond to “bidding wars” by demanding a rent greater than the advertised one. Finally, landlords will be prohibited from asking for more than one month’s rent upfront from tenants.

This welcome news should have happened long ago. The housing crisis didn’t happen overnight. Renters, housing advocates, homeless service providers and others have long campaigned for these measures and more. Building more, rezoning, controlling landlord behavior, raising wages for low-income workers, regulating the market, controlling land prices and values have to happen together. This has been public knowledge for decades.

Vienna has been investing in and supporting social, aka public, housing for decades, and it’s paid off. While the city’s not paradise, it’s a practical response to unaffordable housing. Or take Melbourne. Until 2021, Melbourne was the second most expensive city in Australia. That’s when the city decided that that was an unacceptable situation. Melbourne built more, and it controlled real estate investing, by taxing real estate investors, taxing platforms like Airbnb, taxing vacant properties and land. Will Melbourne’s success continue? Who knows, the point is that the city recognized the patterns.

At midnight tonight, Vancouver will close public comment on the Vancouver Official Development Plan, a plan described as ambitious, thoughtful and well-crafted in vision and intent, on one hand, and faltering in diagnosis and prescription. In the next week or so, voters in the Netherlands and New York City will make their decisions largely based on candidates’ and parties’ promises, proposal, and plans for affordable housing. Let’s make sure the focus is on the residents, the people, living the crisis, rather than the buildings.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: Blandford Fletcher, “Evicted” (1887) / Queensland National Art Gallery)