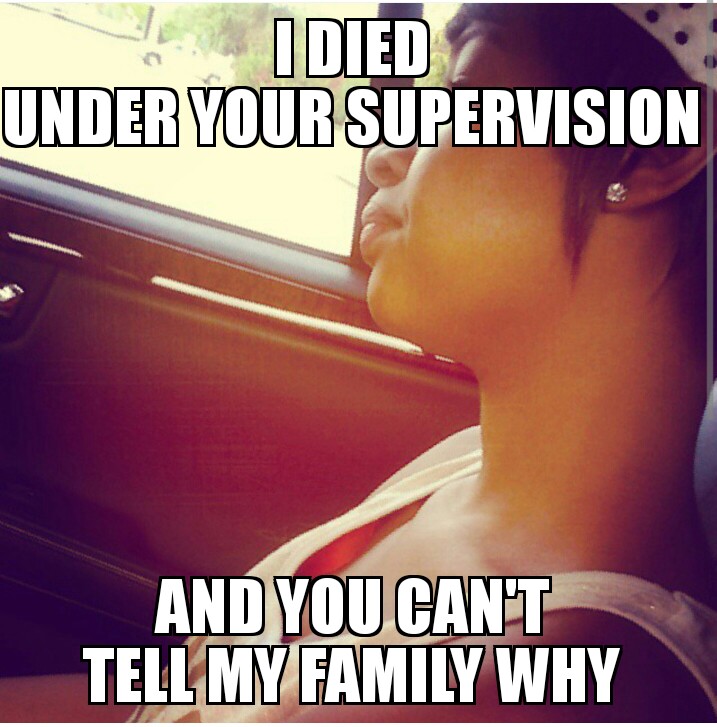

Over the past few months, jails in Kentucky have been making headlines. Earlier in the year, the headlines were about how “a pattern of employee misconduct” in one juvenile jail killed a teenage girl named Gynnya McMillen.

The new headlines, though, are about the jails in Louisville, KY, the largest city in the State. You see, Louisville’s jails are overcrowded. How overcrowded are they? To quote former inmate Jennifer Kennedy, “It was terrible…I slept on the floor, on a mat. I had to borrow a cover from someone who had one in there.”

But wait, there’s more. Louisville’s jails are so overcrowded that the State has deemed it a crisis. The director of Louisville Metro Corrections even ordered the re-opening of an old, now illegal jail. This supposedly temporary jail is illegal because the building is not up to fire evacuation standards. One judge remarked that “If they have a fire there, people are going to die.”

Even when faced with the prospect of a holocaust of prisoners, the State continued putting people in jail, and so the old, illegal jail also filled up. Now prisoners are forced to sleep in gymnasiums and use portable bathroom facilities. With every new “temporary” solution, prisoners get moved around—and moving prisoners is a violent, destabilizing process.

It’s easy to think that this overcrowding crisis is sudden and surprising, but it’s neither. The State of Kentucky created this crisis. Faced with a surplus of revenue and falling wages throughout the commonwealth, state and local governments looked to prisons and jails in which to invest excess capital. More prisons and jails mean more prisoners, an induced demand that does not depend on crime rate. This resulted in the Kentucky having the fourteenth highest overall incarceration rate in the world and the third highest women’s incarceration rate in the world.

First, the State of Kentucky knowingly hyper-incarcerates people, especially women, who worldwide are the fastest-growing prison population. The State keeps demanding more, its thirst for caged bodies never satiated, and puts these prisoners in cramped, fire-prone conditions. State officials throw up their arms, wondering how anyone could have predicted this.

How will Louisville and the State of Kentucky “solve” the crisis? The State government offered to take 200 inmates into its custody from local jails, but the state jails are just as overcrowded; state facilities were already leasing out prisoners to local jails to begin with. Instead, the State is looking to reopen two private prisons run by the CCA as another “temporary” solution. Never mind that the Kentucky CCA facilities were major harbors of sexual abuse against women prisoners.

As Louisville and Kentucky scramble for solutions, two things are clear:

- Women prisoners, and all prisoners, matter. As the State creates and covers up its own crises, women prisoners become targets of violence to solve said crises. The pain their bodies and minds must endure directly correlates to the amount of money the State invests in prison infrastructure. Women prisoners’ space and time are inversely related to these investments. The conditions that women prisoners endure—such as the risk of being burned to death in overcrowded facilities—are also the conditions on which entire modern cities, like Louisville, are currently being developed.

- The solution for prison overcrowding is not to build more prisons or to find more “temporary” solutions. The existence of prisons at all, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore reminds us, is a crisis in itself, a major contradiction in a supposedly “free” society that allows “un-freedom” to exist. The only real, lasting solution is to abolish prisons and create alternative forms of justice that do not inflict more violence on other human beings.

(Photo Credit: WDRB)