In 2018, at the Splendour in the Grass music festival in Byron Bay, New South Wales, Australia, Raya Meredith was strip-searched. Not that it matters, but nothing illegal was found. In 2022, then-27-year-old Raya Meredith filed a class action suit against the police of New South Wales, arguing that the strip-searches conducted at music festivals from 2016 to 2022 were unlawful and constituted assault, battery, and false imprisonment. Her landmark suit now represents 3,000 people who were strip-searched. That case is currently being heard in court. Today, Raya Meredith’s attorneys explained that the New South Wales police admitted the strip-search was unlawful but “objectively reasonably necessary.” What?

Kylie Nomchong, Raya Meredith’s attorney, responded to that claim, ““We get to the quite outrageous submissions … where the defendant is asking your honour to infer that it was objectively necessary to search the plaintiff’s breasts and genital area,” Nomchong told the court. It is unbelievably offensive to assert, without any evidence whatsoever, that there was some objectively reasonable basis on the part of the searching officer to inspect the plaintiff’s vagina, to ask her to pull out her tampon, to ask her to bare her buttocks and anal area and to bend over and drop her breasts. It’s just offensive.”

Justice Dina Yehia, the presiding judge in the case, agreed with Nomcholeng, “I’m not quite sure I understand those submissions, given the way this matter has proceeded.”

What else is there to say? For the police, the violation of a woman’s body and person was, and continues to be, “objectively reasonably necessary.” The objective and reasonable necessity of the strip-searches is so self-evident that just days before the hearing began, the police withdrew 22 witnesses, mostly police … because it was objectively reasonably necessary for them not to speak under oath.

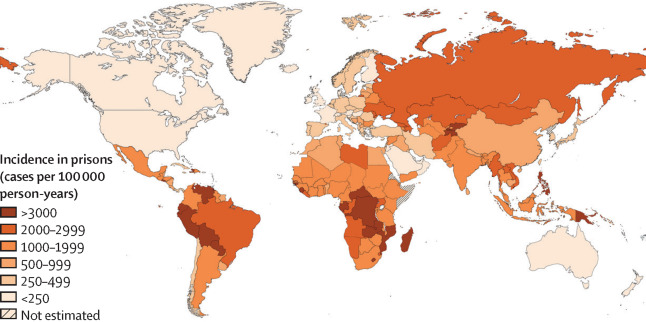

Raya Meredith’s attorneys note that strip-searches seldom “work”, as in produce any evidence of illegal activity. But police engage in them anyway. So, what’s the point and purpose of strip-search? A study published in 2021, the year before Raya Meredith’s encounter with the police, considered the scale and scope of strip-searches conducted by New South Wales police from 2014 to 2018, As Raya Meredith’s attorneys suggest, most of those searches produced nothing, other than trauma and pain. Nevertheless, the use of strip-searches “at music festivals, at train stations, in police vehicles and at other locations” increased. What did the few strip searches that did produce any evidence of illegal activity show? 96% involved drugs, either possession or distribution: “It can be inferred from these data that the strip search regime is primarily being used for the enforcement of the summary offence of drug possession, rather than the serious indictable offences for which the power to strip search was envisaged.” A War on Drugs was declared, and strip-searches were normalized, naturalized, deemed “objectively reasonably necessary”.

When the State declares War on its population, as in a War on Drugs or a War on Crime, it declares a state of exception. That is, it declares a crisis so grave, so threatening to the State that the elimination, ostensibly temporary, of constitutional rights and protections is reasonably objectively necessary. The police in New South Wales were just following orders.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: Roberto Matta, “Nuremberg Judgment” / MoMA)