“Austerity is a profoundly feminist issue.”

Sarah Marie Hall

The headline reads, “‘Trapped:’ Lack of affordable housing for domestic violence survivors”. The story takes place in Nashville, but really it could be almost anywhere in the world. A woman leaves her abusive partner, secures a Section 8 housing voucher, finds a place to live. Then, apparently without warning, she’s given an eviction notice. She’s given ten days to vacate the apartment. With a hot real estate market and landlords loathe to accept housing voucher recipients, she returned to her abusive partner’s residence: “”I feel defeated, I feel hopeless, I feel trapped, I feel like I don’t have a way out … It just kind of sucks the life out of you; it makes you want to give up after you have tried so hard.” It just kind of sucks the life out of you.

Here’s how the story keeps being told: Rents are skyrocketing, eviction filings are rising rapidly, domestic violence survivors are caught in a double, or multiple, bind. It’s a shame, but, you know, market forces are market forces. That story provides an alibi for all predators, in private practice, in this case real estate, as well as at the state level. This is a tale of a public policy of abandonment through austerity. Austerity always targets women. It just kind of sucks the life out of you. Austerity is a policy of laissez faire femicide.

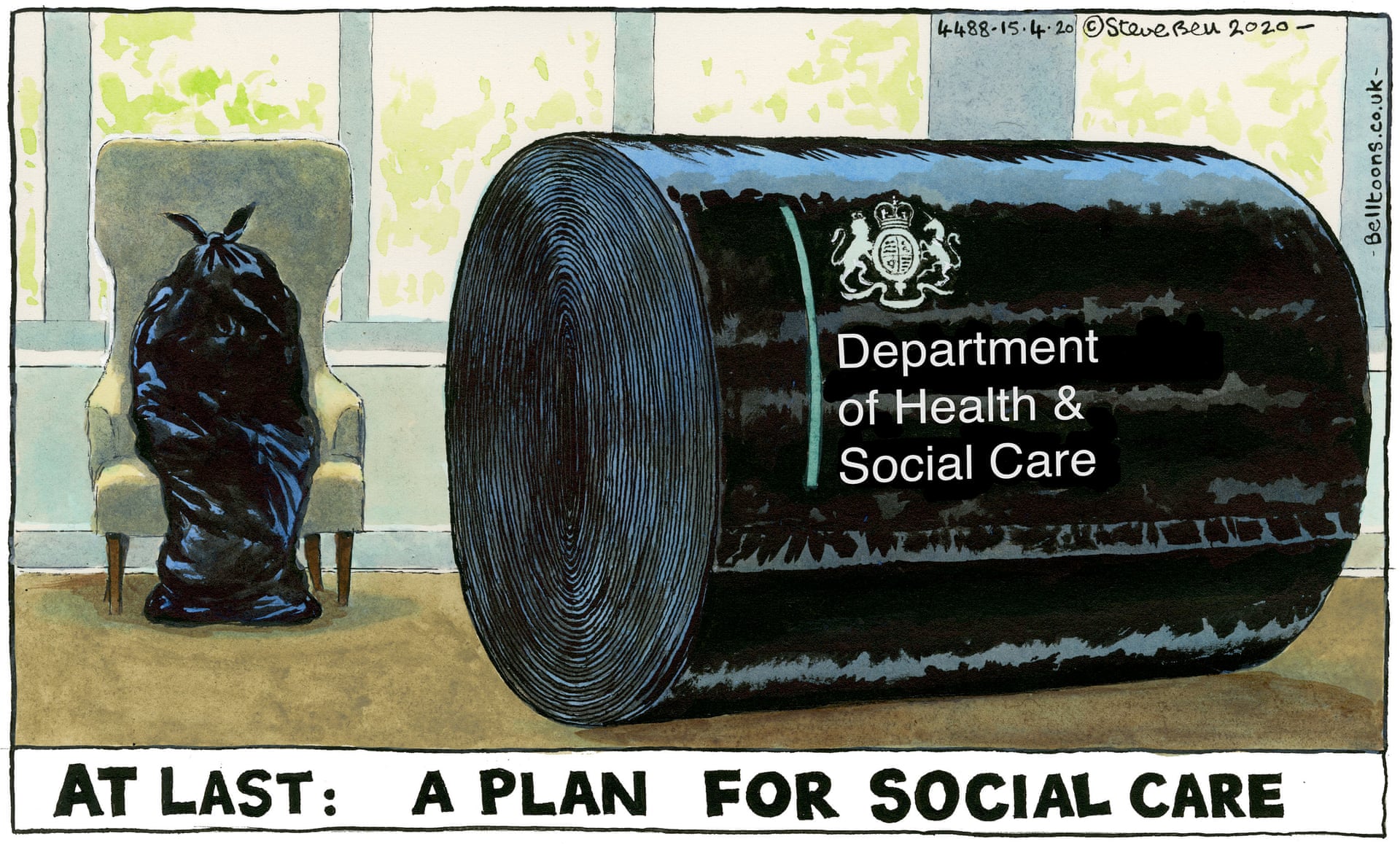

Last year, two reports documented that England’s four year experiment with austerity, 2010 to 2014, resulted in an additional 57,550 deaths. Life expectancy among low-income women, especially women of color, had actually declined. More recent studies show that inequality and poverty in England have had catastrophic effect: “Life expectancy for women in the poorest parts of England is less than the overall life expectancy for women in every OECD country in the world besides Mexico.” Women have been hardest hit by rising poverty, growing inequality, increasing labor market segmentation, all fueled and intensified by austerity. It just kind of sucks the life out of you.

In Brazil, “the burden of retrenchment in social spending in Brazil has been overwhelmingly borne by women”: cuts in social reproduction, such as day-care center; in policies to combat gender-based violence and guarantee economic autonomy; in areas where women represent the bulk of the workforce, such as health and education. Cuts in cash transfer programs, in programs designed to support single-parent families, and programs designed to combat and prevent domestic violence all have targeted and devastated women. It was bad before the pandemic; the last three years have been worse. From Nashville to Rio, the line is direct.

In the Netherlands, from 2011 on, the State cut more than 55 billion euros from its social services budget as it increased taxes in ways which hit the poorest the hardest, especially women of color. The Dutch government claimed it was replacing the welfare state with a “participation society”, in which “everyone who is able, is asked to take responsibility for their own life and environment”. That didn’t work economically for Reagan or Thatcher or Clinton, but it did work politically, stigmatizing anyone and every community needing any sort of assistance. At the epicenter of the assault, women of color.

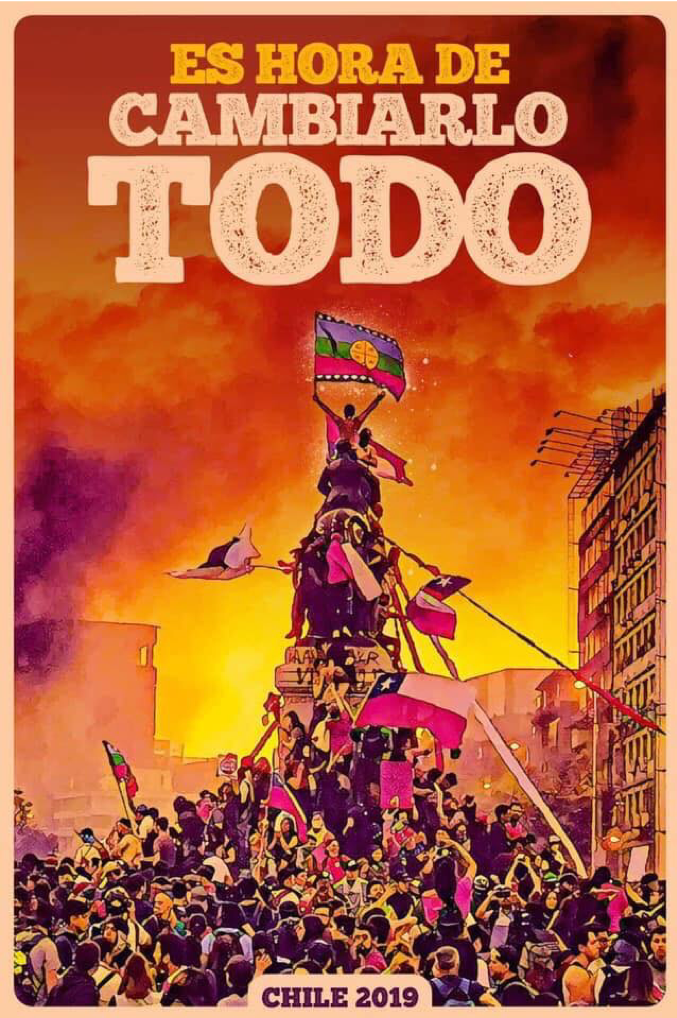

If you are having a sense of déjà vu all over again, that’s because we have been here before, and then again and again and again. So, let’s agree that it’s time, way past time, to stop using the market-forces alibi to justify failed policies that result in the death, slow or fast, of women, and especially of women of color and low-income women. Austerity aims to just kind of suck the life out of you. As such, austerity is a policy of laissez-faire femicide. Really, another, better world is possible.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo credit: Pluto Press)