It only really hit me after coming to the United States to study. It had always been there at the back of my mind, dispersed as unconnected memories of conversations with friends. But now those memories have cohered to form a narrative. The catalyzing event that facilitated this fusion was, and continues to be, my experience of segregation in Washington DC. This is the narrative of segregated reading practices across axes of race and gender. White readers self-segregate in ways that reflect and reinforce physical boundaries that account for persisting racialized gender tensions and inequalities across the country. Segregated reading practices involve avoiding literature by other races and genders, particularly those who have been historically subjected to discrimination. It is a form of literary solipsism where the self, and close approximations to it, is the only candidate worthy of attention in a book of fiction. This literary self-segregation engenders a narrow reading of the world that does little to dismantle prejudicial attitudes and unconscious biases held by those in power.

More often than not the Black people I see within and around my university’s campus are often working in positions of servitude. On seeing this, I wondered whether this accounts for the few times that white students or professionals in the area engage with Black people on a daily basis. Can you imagine that almost every time you see a Black person – especially if you are white – it is to be served by them? And then, when speaking to people about their favorite novels you realize that they rarely ever mention reading books about women and men of color? Can you imagine living in a country where everyone who is not white is flattened and exists outside the range of a white person’s engagement with fully realized human beings, both in the realms of the physical and fictional?

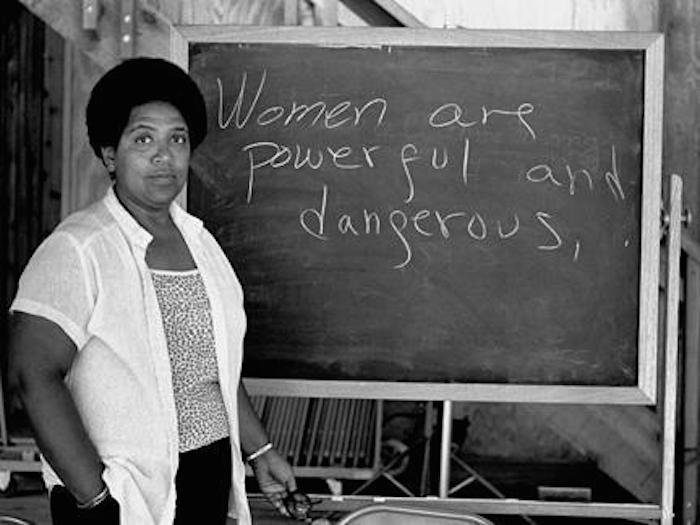

Men do not read enough novels by and about women. This is a simple truism that can be expanded through a race and gender disaggregation. White men do not read enough novels about white women or people of color, white women do not read enough novels about people of color, men of color do not read enough novels about women of color. Women of color, especially Black women, and especially Black women who are queer, occupy the bottom of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s metaphorical basement and have had to read up the ladder of human experience with little reciprocity. This isn’t to say that fiction is a panacea for society’s ills or that it can or should function as a replacement for engaging with actual people. There is certainly a performative aspect to some people’s reading practices, as though reading about Black women, and acquiring the language to speak about them and their experiences, are enough. It isn’t.

However, there is something to be said about the way that people’s lives are separated in the physical realm, and how that gets translated to their reading of the world. There have been too many conversations with men, both white and Black, who would rattle off their favorite books of fiction by other white and Black men while failing to mention a single novel by a white or Black woman. I’ve also often read several online pieces, such as The New York Times’ By the Book, where public figures proudly list the books that impacted them most in life. The majority, if not all, of those books center a white male imprint on human experience.

Another note on segregation. Trains in DC, at least the ones I take, perform a sort of magic. When I get onto the train in central DC there are crowds of white people who are tired after a long day of work, eager to get home, like me, to relax. As the train travels further away from central DC, this crowd slowly disperses until all the Black people – previously hidden among a sea of white – are revealed. Except, this isn’t a magic trick. I almost always know when the last white person in the train car will get up to leave before it ventures into more “dangerous” locales. This is the work of systemic racism that bleeds into how neighborhoods are organized. It bleeds into who we associate with, live next to, empathize with, humanize, and spend time with in books. I knew about segregation and gentrification prior to moving to the U.S. Knowing that didn’t diminish the culture shock.

I’m somewhat pleased to note that efforts are now being made to include more women of color – within and beyond the global – into the fold of lionized literary wunderkinds. Recall former President Barack Obama’s summer reading lists, this year’s Booker Prizes long and short lists, this year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction, and the ever-increasing number of “woke” Bookstagrammers sharing their favorite books by women of color and discussing intersectionality. That most of these Bookstagrammers are women is not surprising, but it is my hope that, with time, the effort to read more books by Black and Brown women will occur in tandem with increased efforts to desegregate neighborhoods and dismantle systemic racism. Whether it’s Cereus Blooms at Night by Shani Mootoo, Beloved or The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, Krik? Krak! by Edwidge Danticat, Lucy by Jamaica Kincaid, An American Marriage by Tayari Jones, Pachinko by Min Jin Lee, Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri, or Americanah by Chimamanda Adichie, it’s time to destabilize privileged locations of storytelling by reading about the constellations of women’s experiences; of women who continue to exist in the margins in the mind of country plagued by a white pathology.

(Photo Credit 1: The Guardian) (Photo Credit 2: ThoughtCo / Robert Alexander / Getty)