Around the world, women are taking to the streets in great numbers, to protest, to take charge, to transform. In the past couple weeks, women have led and populated mass protests and marches in Malawi, Uganda, Lebanon, Argentina, Romania, Chile, Haiti. Women have occupied Wall Street, Nigeria, and beyond.

Women have been the bearers, in every sense, of Spring … in Syria, Tunisia, Yemen, Bahrain. Today, January 25, women are returning to Tahrir Square … and to every square in Egypt. This is nothing new for northern Africa. Women, such as Aminatou Haidar, have born `spring’ in Western Sahara now for decades.

For women, the street does not end at the sidewalk. It runs, often directly, into the State offices.

Women are everywhere on the move, changing the face and form of State.

In Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner returned to her office today, after a 21-day health related absence, to resume her activities as President. On Thursday, January 5, Portia Simpson Miller was inaugurated, for the second time, as Prime Minister of Jamaica. On Monday, January 16, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was inaugurated to her second term, of six years, as President of Liberia.

These are precisely not historic stories or events, and that’s the point. Women in positions of State power are women in positions of State power. Not novelties nor exotic nor, most importantly, exceptions. That is the hope.

But for now, that struggle continues.

In Colombia, women, such as Esmeralda Arboleda, helped organize the Union of Colombian Women, fought for women’s rights and power, and was the first woman elected as a Senator to the national Congress. That was July, 1958. Fifty or so years later, in January 2012, women in Chile launched “Mas mujeres al poder”, “More women in power”. In tactics, strategies and cultural actions, Mas mujeres al poder builds on the work of student activists in the streets. Women are saying enough, women are saying the time is now, and women are pushing their way through the electoral process, with or without the political parties, into the provincial and national legislatures.

Meanwhile, in Bolivia, Gabriela Montaño was named President of the Senate and Rebeca Delgado was named President of the House of Representatives. Women are everywhere … and on the move.

On Tuesday, January 10, voters in Minnesota, in the United States, elected Susan Allen to the state legislature. Allen is the first American Indian woman to serve in that body. She is a single mother, and she is lesbian. Many firsts accrue to her election.

Across Europe, Black women are struggling and entering into legislative bodies with greater and greater success: Manuela Ramin-Osmundsen, originally from Martinique, in Norway; Nyamko Sabuni, originally from the DRC, in Sweden; Mercedes Lourdes Frias, originally from the Dominican Republic, in Italy. The struggle continues … into the national and regional legislatures, into the political structures, into the cultures of power as well as recognition.

Across the African continent, women are on the move. In Kenya, women, such as Charity Ngilu, are set to make their marks in the upcoming elections … and beyond. Meanwhile, South Africa’s Minister of Home Affairs Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma is running, hard, for the Chairpersonship of the African Union Commission. She would be the first woman in that post, and some say she would be the most powerful woman in Africa.

And in South Korea, four women, Park Geun-hye, Han Myeong-sook, Lee Jung-hee and Sim Sang-jung lead the three major political parties. Together, their three parties control 262 seats of the National Assembly’s 299.

This barely covers the news from the past three weeks. Everywhere, women are cracking patriarchy’s hold on and of power, in the streets, in the State legislatures, in the political structures. Today, and tomorrow, women do not haunt the State. They occupy it.

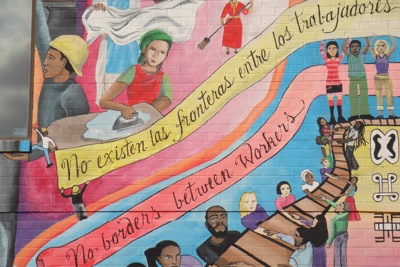

(Photo Credit: BeBlogerra)