In the past day or so, the news has suffered a crescendo of iterations of brutality: police brutality; the brutality of racist, White supremacist violence; and the brutality of designating certain populations as disposable, not important to consider when `opening up’ states, cities, countries. This is a snapshot of today’s three faces of brutality: Collins Khosa; Ahmaud Arbery; and the Arlandria/Chirilagua neighborhood of Alexandria, Virginia.

Collins Khosa, 40 years old, lived in the Alexandra township, in Johannesburg, South Africa. April 10 was the fifteenth day of the national lockdown, a lockdown enforced by both local police forces and the South African National Defence Force, SANDF. On April 10, members of SANDF saw Collins Khosa and a friend in his yard. The SANDF members saw a cup half full of liquid, which they assumed was alcohol. They asked Collins Khosa whether that was the case, and Collins Khosa correctly answered that drinking alcohol on one’s own premises was not a violation of the lockdown rules. The SANDF members then demanded that Collins Khosa step into the street, so that he might be taught a lesson. Then the SANDF members taught. They beat Collins Khosa to death. Now the Khosa family is in court, demanding an investigation. As they explain, their “case is not about the justification for the lockdown or its extent. It is about combating lockdown brutality”. Lockdown brutality. Leading South African constitutional lawyer Pierre De Vos asks, “Why has there been less public outrage (and less debate) about Khosa’s death and about other lockdown brutality by law enforcement officials, than there has been about the ban on the sale of cigarettes, on the one hand, and about those complaining about the ban, on the other? Is it because soldiers largely patrol working class and poor areas and not the leafy suburbs where most white people live? Is it because victims of brutality have been predominantly black? Or is it because the perpetrators of the abuse have been largely black?”

The past two days have seen numerous reports of lockdown brutality across South Africa, and South Africa is not alone. For example, it was reported yesterday that in Brooklyn, in New York City, of the 40 people arrested for violation of social distancing, 35 are Black, 4 are Latinx, 1 is White: “The arrests of black and Hispanic residents, several of them filmed and posted online, occurred on the same balmy days that other photographs circulated showing police officers handing out masks to mostly white visitors at parks in Lower Manhattan, Williamsburg and Long Island City. Video captured crowds of sunbathers, many without masks, sitting close together at a park on a Manhattan pier, uninterrupted by the police.” Why has there been less public outrage and less debate?

At the same time, videos circulated showing the cold-blooded murder of Ahmaud Arbery. Ahmaud Arbery was a 25-year-old Black man, a former high school football player, an active athlete, an all-around good guy. Ahmaud Arbery went jogging through a neighborhood in Brunswick, Glynn County, Georgia. Two White men decided that Ahmaud Arbery was dangerous `resembled’ someone suspected of burglary. There were no burglaries, there was no suspect, there was no reason, other than that of Being Black. Being Black was evidence enough of criminality. The two men followed, hunted, Ahmaud Arbery and shot him, killing him. The two men were not charged with any offense. That all happened February 23, in the early afternoon. Only this week a video emerged showing what actually happened. Only this week were the two White men finally taken into custody. Had it not been for the video, they would be free as any other White man with a gun in the United States. Needless to say but it must be said, Ahmaud Arbery was unarmed. The line from police brutality to `citizen brutality’ in the prosecution of some imaginary crime is a short, direct line.

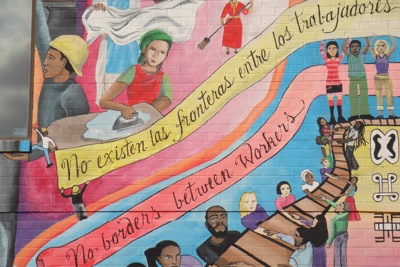

The Commonwealth of Virginia released Coronavirus data this week, the same week that the Governor, a medical doctor, announced that it was time to start `re-opening the state. The data was broken down by postal zip codes. In the small northern Virginia city of Alexandria, itself hotspot, one zip code stood out, 22305, the largely working-class, Latinx immigrant and first-generation neighborhood of Arlandria/Chirilagua. In Arlandria, a community of around 16,000 residents, 608 residents were tested, and 330 tested positive for Covid-19. That’s an extraordinary 55% of the test population testing positive. Why have so few been tested? Because so many are deemed `ineligible’ because of status or income. That leads to a situation in which people only get tested if they can pass various stringent hurdles. In a press conference today, the Tenants and Workers United, a chapter of New Virginia Majority, demanded “expanded access to testing, ensuring tests and treatment are free, and providing housing so that residents can safely isolate.” Repeatedly, they invited Governor Ralph Northam to leave the Governor’s Mansion and come to Alexandria to see what’s actually happening. Earlier in the week, the Legal Aid Justice Center responded to Northam’s plan to `re-open’ Virginia by labelling the proposal “reckless and cruel”. As Legal Aid Justice noted, “Due to systemic racial inequities, infection and death rates are highest in Black and brown communities. In our state capital of Richmond, 15 of the 16 deaths from COVID-19 were Black residents. In Fairfax County, while only 17% of the population is Hispanic, 56% of all confirmed cases are Hispanic.”

It’s all cruelty actually, rather than brutality. Brutality suggests that those committing the acts of violence are somehow “brutes” or “animals”. Cruelty, on the other hand, suggests that those committing the violence range between indifferent to the pain of others to actually taking pleasure in inflicting pain on others. As with the Khosa family pursuit, this concerns more than this particular police officer or that particular White racist, although they must be addressed. It addresses the whole system of disposable populations, a Black man sitting in his front yard, a Black man jogging down the street, an entire Brown neighborhood, all of them trying to make it through another day. Why has there been less public outrage and less debate? We must address the cruelty that structures our lives.

(Photo Credit 1: Daily Maverick) (Photo Credit 2: New York Times) (Photo Credit 3: Tenants and Workers United / Facebook)

At the beginning of the 20th century, the slum dwellers of Glasgow, Scotland, were faced with predatory landlords, rising rents and a government that was hand-in-glove with the slum owners, the `urban developers’ of the day. Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, the working poor of Alexandria, Virginia, face predatory landlords and, again, a local government that is hand-in-glove with the latter-day developers. In both instances, the weapon du jour is mass eviction. From Glasgow to Alexandria, from then to now, women have organized to stop the evictions and to secure justice.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the slum dwellers of Glasgow, Scotland, were faced with predatory landlords, rising rents and a government that was hand-in-glove with the slum owners, the `urban developers’ of the day. Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, the working poor of Alexandria, Virginia, face predatory landlords and, again, a local government that is hand-in-glove with the latter-day developers. In both instances, the weapon du jour is mass eviction. From Glasgow to Alexandria, from then to now, women have organized to stop the evictions and to secure justice.