Amanda Burrows

Who sets housing policy where you live? Renters? Homeowners? Or both? Does anyone in charge of housing policy in your area really know anything about the experience of facing eviction or, more drastically, of being evicted? Recently, Amanda Burrows announced her candidacy for the mayoral nomination of Vancouver. Burrows is “a prominent social justice advocate in Vancouver” as well as Executive Director of FIRST UNITED, a faith-based community services provider. Vancouver is Canada’s least affordable city. Burrows knows that. As she explained in a recent interview, “I have been evicted before, which is so many people’s stories in this city: being severed from the community and not finding a place to live because there’s barely any vacancy and it’s so expensive. I couldn’t even find a place if I wanted to.”

Burrows explicitly raises the question of renter representation in her campaign. In a world in which global, national and local economies have equated “wealth” and “development” with greater and growing inequality, increasing numbers of people are facing the varied and yet not so varied landscapes of “affordable housing crisis”. Part of that means more and more folks are renting. For example, according to a recent report, in the United States “the share of first-time home buyers dropped to a record low of 21%, while the typical age of first-time buyers climbed to an all-time high of 40 years”. That means many are putting off buying a home, and leaving the rental markets, for over a decade.

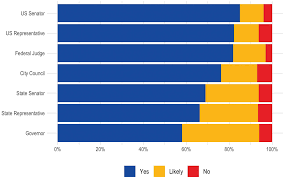

In 2022, researchers from Boston University and the University of Georgia published a report, “Who Represents the Renters?” The researchers pored over the data concerning 10,000 local, state and federal officials. Guess what they concluded? “We find that renters are starkly underrepresented by a margin of over 30 percentage points—a gap that persists across a variety of institutional and demographic contexts. Public officials are substantially more likely to own single-family homes that are more valuable than other homes in their neighborhoods. Collectively, these findings suggest deep representation inequalities that disadvantage renters at all levels of government.” 89% of city councilors were homeowners in sample cities where homeownership hovered around 51%. 83% of mayors and 76% of city councilors were homeowners. Finally, the average homeowning officeholder’s property was worth 50% more than the median value in their ZIP code.

The report concludes, “The underrepresentation of renters among elected officials is troubling and affects the kinds of policies discussed on the local and national stages.” Troubling, indeed. The troubling is not about this councilmember or that mayor, but about the composition of the body that decides, and in many instances creates, housing policy, and therefore housing itself. You may or may not live in Canada or the United States, but wherever you live, the question of renters and homeowners pertains. Amanda Burrows may or may not be elected, although I for one wish her well. The question here is the question asked by researchers a few years ago, as by researchers in mid-nineteenth century England: Who sets housing policy where you live? Renters? Homeowners? Or both? Does anyone in charge of housing policy in your area really know anything about the experience of facing eviction or, more drastically, of being evicted? Who speaks, whose voices and experiences are excluded?

Homeownership rates by office category

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: Kate Hyslop / The Tyee) (Infographic: Katherine Levine Einstein, Joseph T. Ornstein & Maxwell Palmer, Who Represents the Renters)