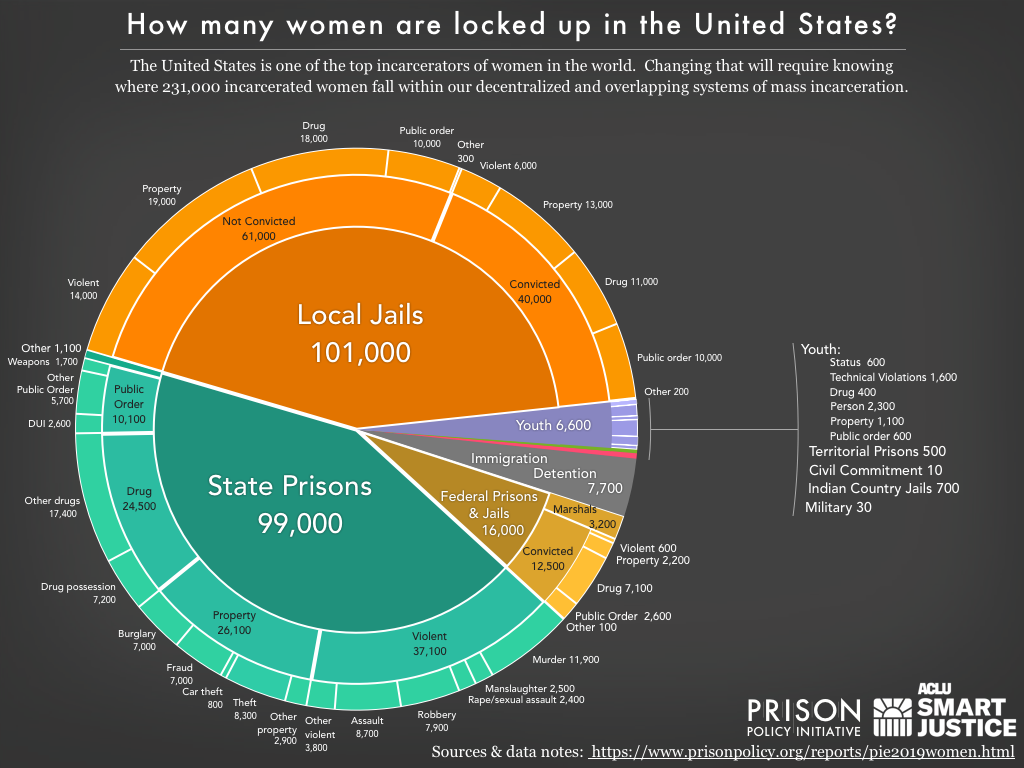

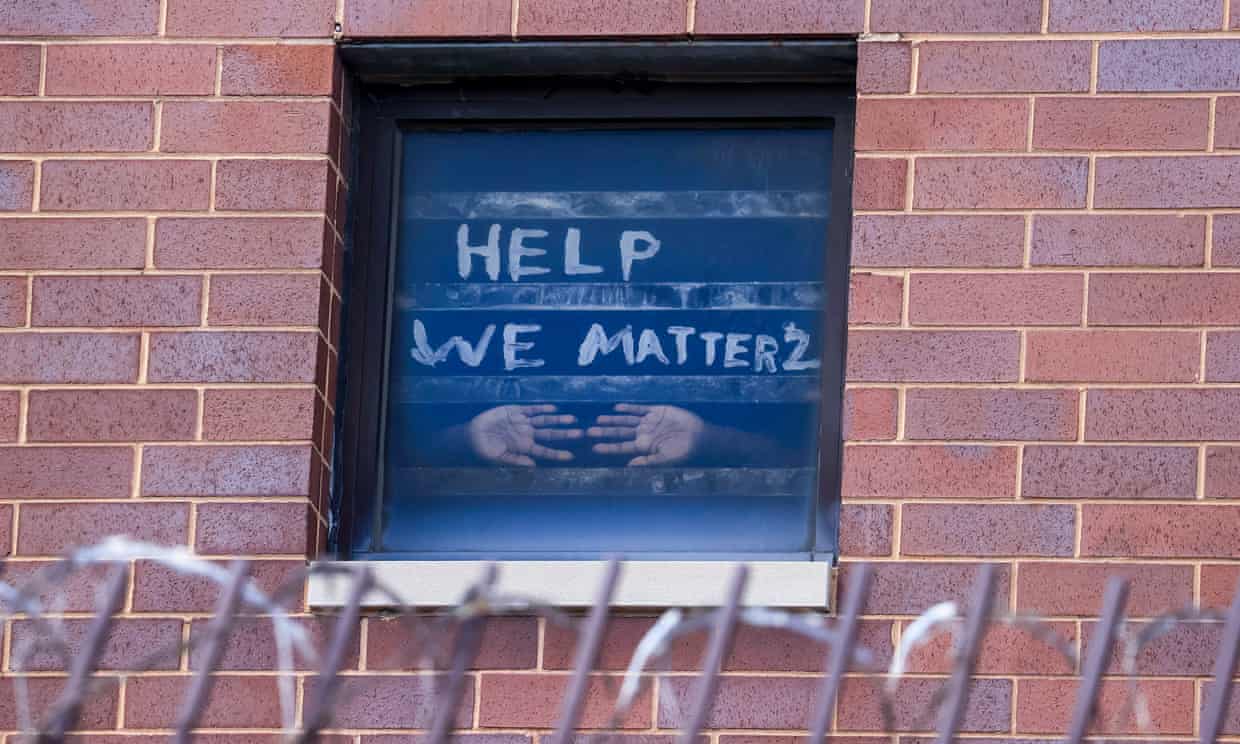

On April 28, Andrea Circle Bear died in federal custody, becoming the first woman to die of Covid-19 while in federal custody. Andrea Circle Bear was convicted of a minor offense and should never have been in prison in the first place. When Andrea Circle Bear was sentenced, she was five months pregnant; she should never have been in prison. You know what killed Andrea Circle Bear? Prison. On Saturday, August 15, Wendy Campbell died, of Covid-19, in federal custody. You know what really killed Wendy Campbell? Prison. Both Andrea Circle Bear and Wendy Campbell died in FMC Carswell, in Fort Worth. Wendy Campbell is the fifth woman to die at FMC Carswell. You know what killed all five women? Prison. FMC Carswell is a Petri dish of inhumane conditions. So is Coyote Ridge Corrections Center, in eastern Washington state, according to a nurse who works there. From sea to shining sea and beyond, you know what’s killing inmates? It’s not Covid. It’s prison. And thus far we have done absolutely nothing to change that situation. Instead, we blame “the pandemic” for the constructed environments we have built.

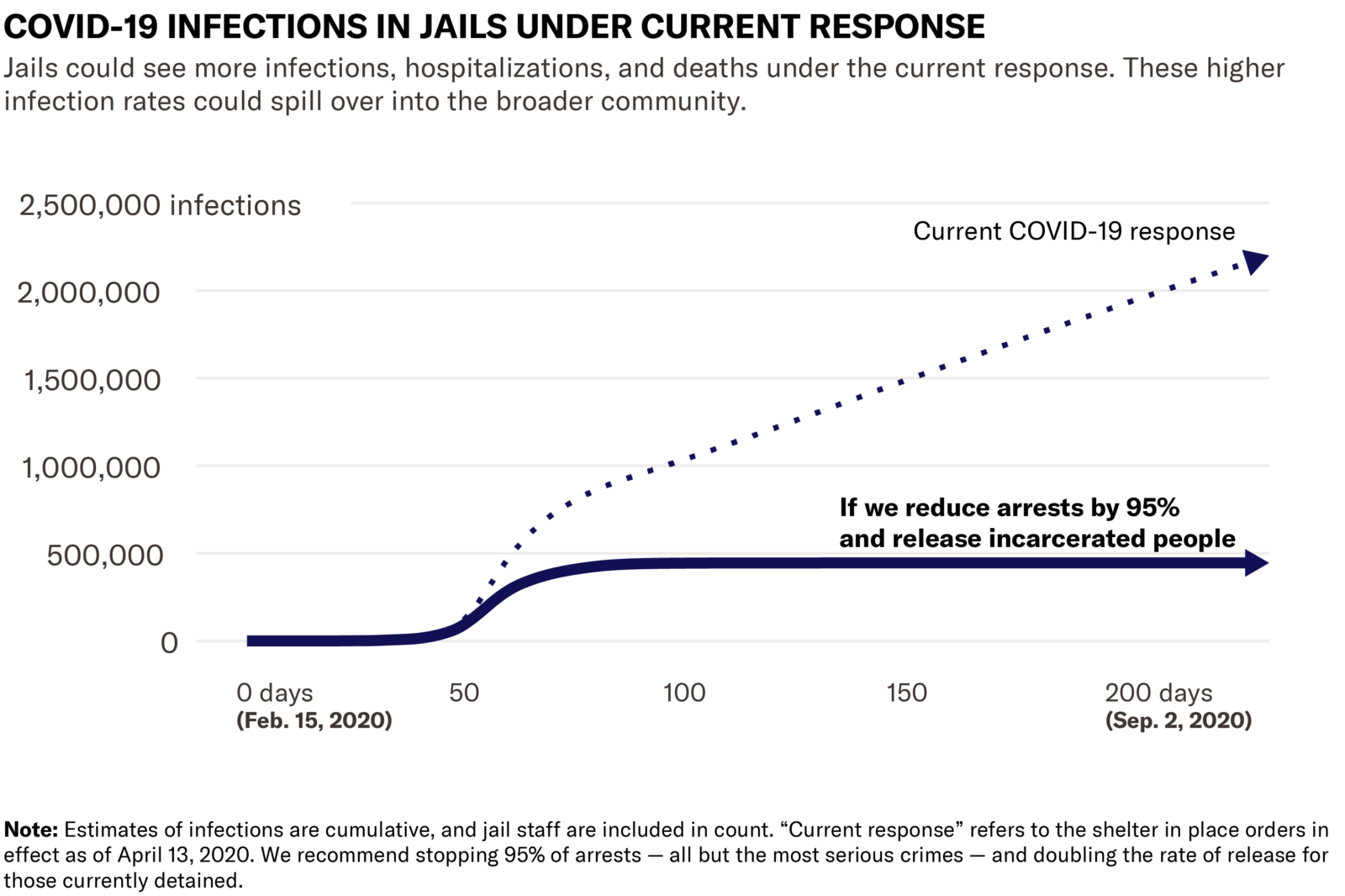

Day after day, we `discover’ that clusters have formed in prisons, jails, immigration detention centers. We claim to express shock that overcrowded toxic spaces are overcrowded and toxic. In India, we `discover’ that overcrowded toxic prisons and jails are overcrowded and toxic. In Malawi, we `discover’ that overcrowded, toxic, far from home jails are overcrowded and toxic. In Mexico, we `discover’ that overcrowded, toxic, famously lethal prisons are overcrowded, toxic, and deadly. In Namibia, we `discover’ that overcrowded, toxic prisons and jails are overcrowded and toxic. We also `discover’ that inmates know the situation and are terrified.

In North Carolina, we `discover’ that a pregnant woman, in this instance eight-month-pregnant Brittany Cowick, has to organize, got to Federal court and more in order to be released to house arrest from a local jail that has reported high rates of Covid-19 infection.

These `discoveries’ all occurred within the last 48 hours. They will recur in the next 48 hours. After a half century of mass incarceration, the time for discovery is over. How often must we `discover’ that the largest prison clusters are in jails and prison? Where is the outrage at this repeated farce of innocent discovery? Six months into the pandemic, why must pregnant women and their allies struggle so hard to be released from deathtrap jails, prison, detention centers of all sorts? What is the point of a word like “vulnerable” or a phrase like “compassionate release” in this landscape? You know what killed Wendy Campbell? Prison. And you know who put her there? You did, I did, we all did. Stop discovering, release them now. How many deaths does it take?

(Photo Credit: The Guardian/Tannen Maury/EPA)