I exist as a contradiction, but a contradiction that has formed a part of my understanding of self and how I interact with women within and outside the Hispanic, Latina, and Chicana communities.

I grew up hearing the term gringa. I believed I could not be one, because of the Hispanic that was ¼ of my blood and an even greater part of my personal consciousness. I believed that I had escaped that title, one that stung of ignorance and outsiderness, but I had not.

I began my work at Tenants and Workers United, also known as Inquilinos y Trabadores Unidos, two weeks ago. I came in as an unpaid student researcher, overly ready to engage easily with the women in the organization.

The dreams I had of being recognized as my mother often is, as a Hispanic woman, were dashed as my short hair, pale skin, and introduction as a university student earned me the title of gringa. I was intimidated by this title and I doubted not only my heritage, but also my ability to speak Spanish with these women. My Castellano lisp gave my Spanish away as European learned, and my insecurities silenced me.

At this point, the erasure of my heritage was almost complete. The constant work to keep my grandmother alive in me through my hispanidad felt threatened. Was it possible to be a gringa and Hispanic?

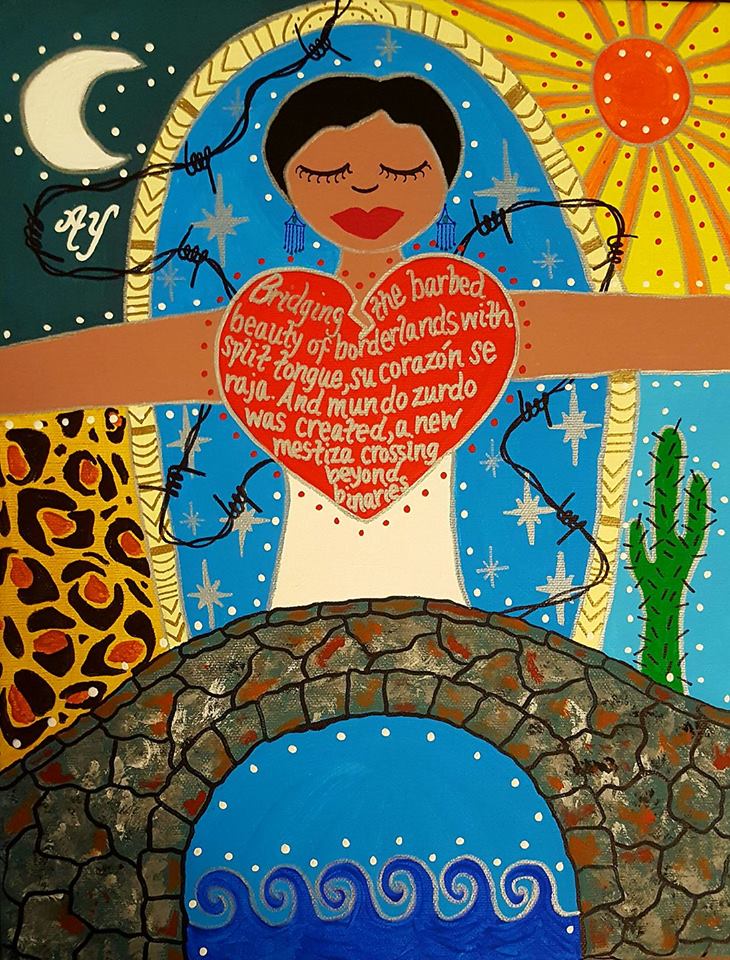

I was at a frontera spoken of by Gloria Anzaldúa. I came in as different, an outsider, but the realization that the women I work with often feel the same way in US society changed my understanding of the situation. Their language and lifestyles often push them to the fringes of US communities and limit their access to resources they need to live a positive and fulfilling life. The mix we two ‘outsiders’ create is not negative, but instead a powerful one filled with all the positive aspects for unification and change. It became less of fitting in, and instead a finding a common ground for establishing a nosotros, a we.

Who am I at this frontera? What can I/ should I bring? What can I take away? How can I help to make this fontera a place that women can inherit proudly and safely? These questions fuel the research that I am now doing at TWU. I am brining what I have access to in order to make the goals and dreams of the Women’s Group realities.

As a Hispanic gringa I bring a contradiction, a hybrid, una nueva identidad to the conversation. I have seen a different side of the conversation and bring a new view. My outsider gains power at this nueva fontera.