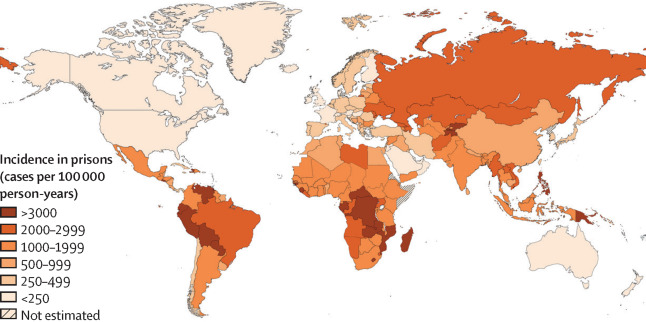

Estimated tuberculosis incidence in prisons (cases per 100 000 person-years) by country in 2019

We’ve passed the hottest day in recorded history. How’s it going, otherwise? Let’s consider the world of prisons, jails, and other forms of locking people up and away. Here’s how we’ve been, at least how we’ve been recorded over the last couple days. Yesterday, the European Court of Human Rights condemned France for its cruel and usually overcrowded and otherwise degrading prisons. Also this week, France’s Inspector General of Places of Deprivation of Liberty condemned the prison in Perpignan for “undignified conditions”. Ireland has the highest number of prisoners and the greatest levels of overcrowding in its history. Women in the Western New Mexico Correctional Facility are suffering state torture and dying at alarming rates. A teenage Aboriginal girl held in Kurlana Tapa Youth Justice Center tried to kill herself. Authorities refused to notify anyone. Why would they? It’s just another Aboriginal prison statistic. And finally, globally, nearly half of all TB cases in prisons and jails go undetected. Incarcerated people are dying. This is a skim of the past four days.

In 2020, 32 incarcerated people from six prisons sued France for inhumane conditions, especially for intense overcrowding. At the center of this was the Fresnes Prison, the second largest prison in France and one of three prisons `serving’ the Paris region. At the time, France’s prisons were at around 116% capacity. Fresnes Prison was at close to 200% capacity. The European Court of Human Rights convicted and fined France for violating inmates’ rights, specifically “the prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment and … the right to an effective remedy”. Fresnes Prison had already been convicted for similar offenses two years earlier. Yesterday, the same European Court of Human Rights again convicted and fined France, again for violation of rights in Fresnes Prison. This time, along with the general conditions, especially the overcrowding, the plaintiffs also protested full body searches. Today, France’s prisons are at 120% capacity. Given the mass arrests of those protesting police violence, that situation is expected to worsen. Meanwhile, the Inspector General of Places of Deprivation of Liberty published her findings concerning the conditions at the Perpignan Prison, in Pyrénées-Orientales Department in southern France. The report begins by noting that a place designed for no more than 132 persons currently houses 315, or 239% capacity. From there the report went downhill: “endemic overcrowding, toxic material accommodation conditions, unsanitary conditions, proliferation of pests, systematic searches, disproportionate use of force and means of restraint”. This is not the first time that the prison in Perpignan has been cited. Plus ça change …

Speaking of the eternal return of the same, the Irish prisons are overcrowded at a historic level. The most overcrowded is the Dóchas Centre, which is at almost 120% of capacity. The Irish government is reported to be “scrambling” now in response, despite this being a longstanding issue. Rather than build more mental health facilities and more support services, the response has been to build more prisons.

Yesterday, a one-on-one companion observer for incarcerated women at the Western New Mexico Correctional Facility (WNMCF) published her observations of the lethal conditions in the institution, where last three years three of her patients died of suicide and many others attempted suicide: “not only did the prison staff fail to save these women’s lives, but the abuse, neglect, disregard, and maliciousness of prison staff pushed them to the point of desperation that made them feel death was the only option.” They didn’t fail, they refused. In 2022, New Mexico paid over $860,000 to settle allegations of rape and sexual abuse at its women’s prisons. Again, staff “failed” to respond to appropriately, “looking the other way”. They didn’t fail; they refused. There’s a humanitarian crisis at Western New Mexico Correctional Facility … and beyond.

There’s a humanitarian crisis at the Kurlana Tapa Youth Justice Centre as well. The Kurlana Tapa Youth Justice Centre is the only juvenile detention center in South Australia. This week, it was reported that an Aboriginal teenage girl tried to commit suicide in early 2023, and the detention center didn’t inform anyone for months. Actually, they never did actually report the incident. They didn’t see the need. The girl, a sexual abuse survivor, was arrested on some minor offences. Bail was recommended, but because of mental health issues, she was remanded for assessment. When she tried to commit suicide, the staff intervened and took her to the hospital. Then, they reported that they took her to the hospital as a precaution. It was only two months later, when her attorney read court-ordered hospital psychiatric reports, only then did she find out that her client had tried to kill herself. The prison staff never informed her of that. They didn’t fail, they refused. Lately, children at Kurlana Tapa have been locked in their cells 23 hours a day, and incidents of self-harm have skyrocketed. Australia finds this “shocking”.

Finally, a study came out, reported on this week, that studied the global situation of tuberculosis in prisons and jails in 2019, that is prior to Covid. The study found the following: “The high incidence rate globally and across regions, low case-detection rates, and consistency over time indicate that this population represents an important, underprioritised group for tuberculosis control. Continued failure to detect, treat, and prevent tuberculosis in prisons will result in unnecessary disease and deaths of many incarcerated individuals.” Nearly half of TB cases among incarcerated people go undetected. Again, not failure, refusal.

From France to Ireland to the United States to Australia to entire world, prisons and jails are dangerous and often lethal. If we know, as we now do, that prisons and jails, especially but not only overcrowded institutions, breed tuberculosis which goes `undetected’ if we know, as we now do, that sending people to those places results in `unnecessary disease and deaths’, and we won’t discuss the concept of necessity here, how can we continue to send people, women, children, anyone, to those places? Just another day or two in the life (and death) of an incarcerating world.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Infographic Credit: The Lancet Public Health)