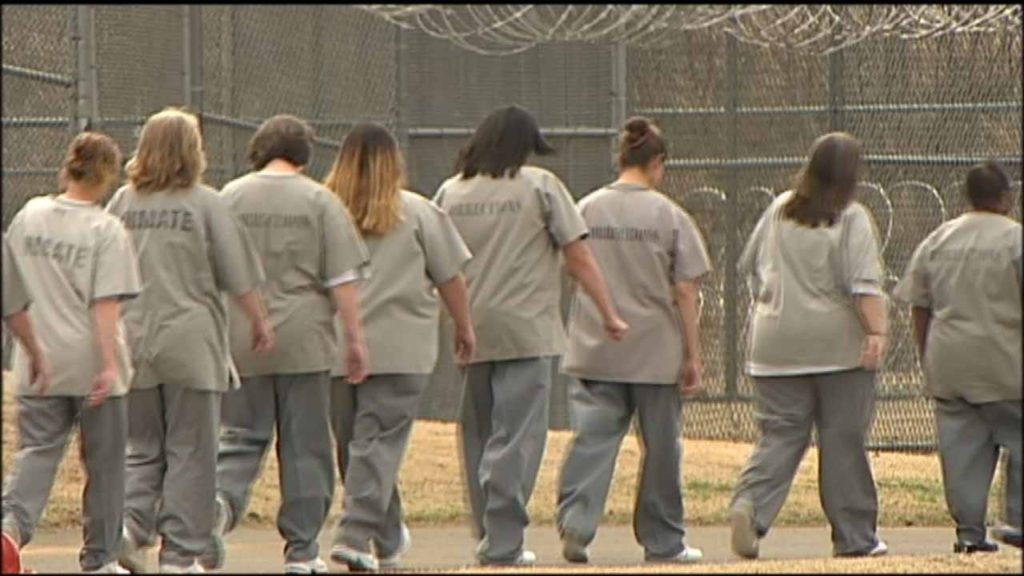

Since 1991 Oklahoma has consistently had the highest female incarceration rate in the United States. For 25 years, Oklahoma has consistently led the nation in its race to the bottom and beneath. This year is no different. According to Oklahoma Watch, “Despite years of concern over Oklahoma’s high rate of female incarceration, the number of women sent to prison jumped again in the latest fiscal year. In fiscal 2016, which ended June 30, the number of women sent to Oklahoma prisons rose by 9.5 percent, from 1,593 to 1,744, data from the Oklahoma Department of Corrections shows.” There is one somewhat bright spot: “Tulsa County … sent 24 percent fewer women … The drop over the past two years there was 49 percent for women … Tulsa County inmate advocates and criminal justice officials attribute the decline to a widely coordinated effort to provide diversion and treatment programs.” Last year, Oklahoma County sent 33 percent more women to prison than the year before. All the other counties combined sent 10 percent more women to prison. At the end of August, Oklahoma prisons were at 107 percent capacity. Except for Tulsa County, none of this is new.

Year in, year out, the same over all report emerges from Oklahoma, and the only exceptions, such as they are, have been an intensification of atrocity and torture. In Oklahoma, most women sent to prison are mothers. For years, Oklahoma has studied the impact of so many mothers being imprisoned, especially on their children, and for years Oklahoma has done nothing … or worse. For years, Oklahoma has known that the majority of women prisoners are [a] dealing with drug and alcohol addiction and [b] are in for drug related offenses, usually minor ones at that, and for years, Oklahoma has increased the punishment for those offenses. For years, Oklahoma has known that, in any given year, it has the highest rate of sexual abuse and rape in women’s prisons, and done nothing. Much of that abuse comes from guards. For years, Oklahoma has known that its prisons put women in debt bondage to prison banks, and Oklahoma looked the other way. For years, Oklahoma has known that an extraordinarily high proportion of women prisoners are living with mental illnesses, and that much of that derives from traumatic experiences. Again, Oklahoma did nothing … or worse.

As Susan Sharp showed, in Mean Lives, Mean Laws: Oklahoma’s Women Prisoners, Oklahoma did more, and less, than nothing. Oklahoma chose its path. It chose to lead the nation in the incarceration of women, and it chose turn women’s well being into trash: “Oklahoma ranks 48 in the United States in the number of women with health insurance and first in poor mental health among women.” Oklahoma is not only mean to women. It’s the meanest. That’s why the news from Tulsa County is so important. How has Tulsa County begun to reduce the rates of women’s incarceration? Nothing spectacular, but rather common sense and evidence-based programs: treatment, education, counseling, “specialty courts”, diversion and a commitment to caring about the well-being of women. More importantly, why did Tulsa County embark on a new path? There was no great political pressure, either in the county or the State, to do so. Instead, people decided that sending women to prison for next to nothing and then keeping them in the system for life was destructive: to the women, their children, their communities, and everyone.

Tulsa County is showing that in Oklahoma, the worst of the worst, it’s possible to change the present, to not condemn anyone to recall a future already condemned. Another Oklahoma is possible, and it begins with valuing the well-being of women.

(Photo Credit: Newson6)