Danielle Hicks-Best today

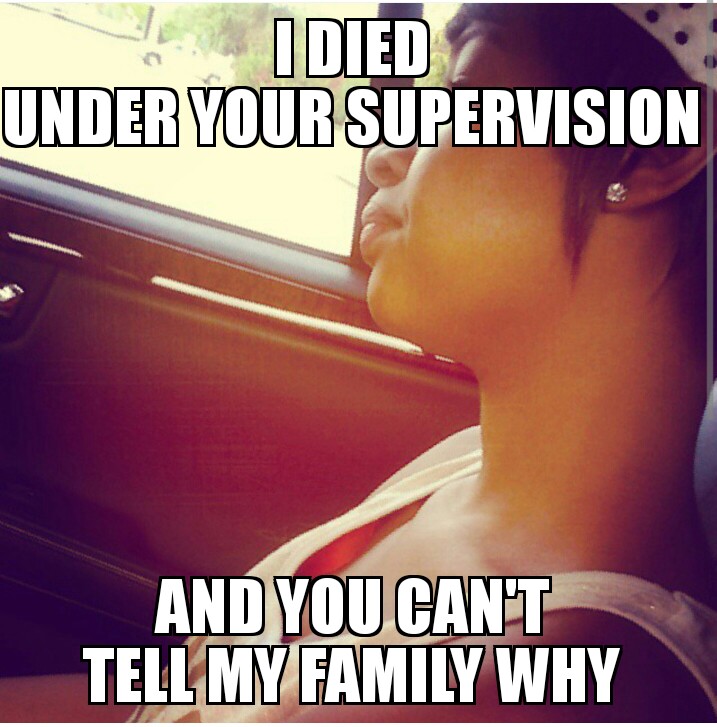

In 2008, when Danielle Hicks-Best was eleven years old, she was raped … twice. She reported the rape to the District of Columbia Police Department. As happens so often, the police did not do nothing. They arrested the eleven-year-old Black girl, Danielle, for filing a false report. There was medical evidence of sexual violence, and it didn’t matter. The police focused on the girl in front of them rather than the men who had committed the violence. The same thing had happened to Lara McLeod, in nearby Prince William County, who explained, “People say rape is serious and you should report it, but look what happened to me: I reported my rape and they told me it never happened.” Danielle Hicks-Best is even more succinct, “I’ve given up on justice. I’m at the point where I no longer hope for anything to come out of this case.”

And that’s the point. The reports suggest that the State “failed” Danielle Hicks-Best. There was no failure in Washington, DC, or in Virginia or in all the other places, around the world, where this story is continuously repeated.

The State, got exactly what it wanted, what it pushes strenuously to get: a woman living with trauma, agony and pain who has learned to silently absorb injustice directed at her as a woman. Ask Veronica Best, Danielle’s mother: “After 11, she lost the rest of her childhood.” There was no failure, because no one cared enough to begin an investigation.

The police now say the arrest and subsequent treatment of Danielle Hicks-Best was “tragic.” While searingly painful and horrible, the actual event was too common by far to qualify as tragedy. Turning rape survivors into liars is part of a program of mass criminalization and hyper-incarceration, and the younger the survivor the more brutal and intense the State violence against them. In a country where girls go to jail for status offenses and boys … will be boys and so are left free, this is no surprise. Girls and women are convicted of the crime of having survived and of having given testimony. For girls and women, speaking is crime. It’s the price of citizenship in the new democracies.

Remember that as you read or ponder the stories of Danielle Hicks-Best or of Lara McLeod. The State got what it wanted. It’s time for us to get the State we want.

(Photo Credit: Washington Post / Sarah L. Voisin)