How many women in how many jails, in this country in this century, are delivering their children, completely alone, and not only without but deprived of the supervision of medical staff? Too many, and too many go uncounted, unreported. As we noted two years ago, when discussing the stories of Diana Sanchez, Tianna Laboy, Kenzi Dunn, all forced to give birth alone in their respective jail cells, “These are only the names we know. There is no national data base concerning prison or jail births … because, really, who cares?” Add Kelsey Love to the list of women who have been forced to undergo these `archaic’ conditions, this torture.

Kelsey Love is now 32 years old. On May 14, 2017, on Mother’s Day, Kelsey Love was eight months pregnant. She was driving her grandmother’s car when she was stopped by police officers in Frankfort, Kentucky. Initially, she was stopped because police thought she was driving erratically. Her grandmother had reported the car stolen. Love told police officers that, not too long before her being stopped, she had used methamphetamine and opioids. She also informed the officers she was eight months pregnant. Then she was booked into the Franklin County Regional Jail, where she was supposed to be monitored every ten minutes. That did not happen.

According to Kelsey Love’s report, on May 16, Kelsey Love began feeling intense pain. She screamed for help. Staff thought she was detoxing, and so left her alone, screaming, in pain. Finally, a female staff member came in. By that time, Love was on the floor, crying, and screaming for help. She asked to see a doctor. She said something was wrong, that the baby was coming out. The staff member asked if she was having contractions, and Kelsey Love said she was. The staff member called the jail call nurse, who said she would check in later and the staff should keep close watch. That did not happen.

Three hours later, the nurse arrived. When she and a staff member walked into the cell, the floor was covered in blood. Kelsey Love had given birth to a baby boy, chewed off the umbilical cord, ripped the mattress and crawled into the bed with her newborn child. That is what happened.

Kelsey Love sued the jail and some members of the staff. This week, she was awarded $200,000 in an out of court settlement. Kelsey Love has successfully completed drug rehabilitation treatment, has been clean and sober for two years, and is now working to regain custody of her children. The boy born on the floor of that jail cell will turn four in three months.

According to Kelsey Love’s attorney, “She’s doing great.” According to the same attorney, she “still has night terrors as a result of her ordeal.” What happened to Kelsey Love? She was abandoned, as so many women have been, left to give birth alone on the concrete floor of a jail cell in Kentucky, just like Tianna Laboy in Connecticut, Kenzi Dunn and before her Tamm Jackson in Florida, Diana Sanchez in Colorado, Jessica Preston in Michigan. Nicole Guerrero and Autumn Miller in Texas. These are only the names we know. There is no national data base concerning prison or jail births … because, really, who cares? It’s not archaic. It’s torture, cruel and unfortunately altogether usual punishment.

by Dan Moshenberg

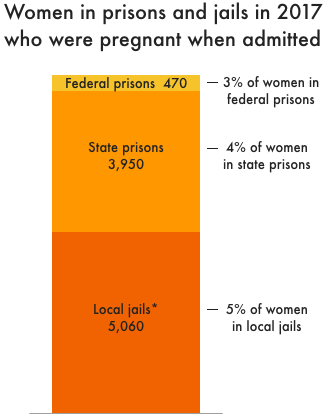

(Infographic: Prison Policy Initiative)