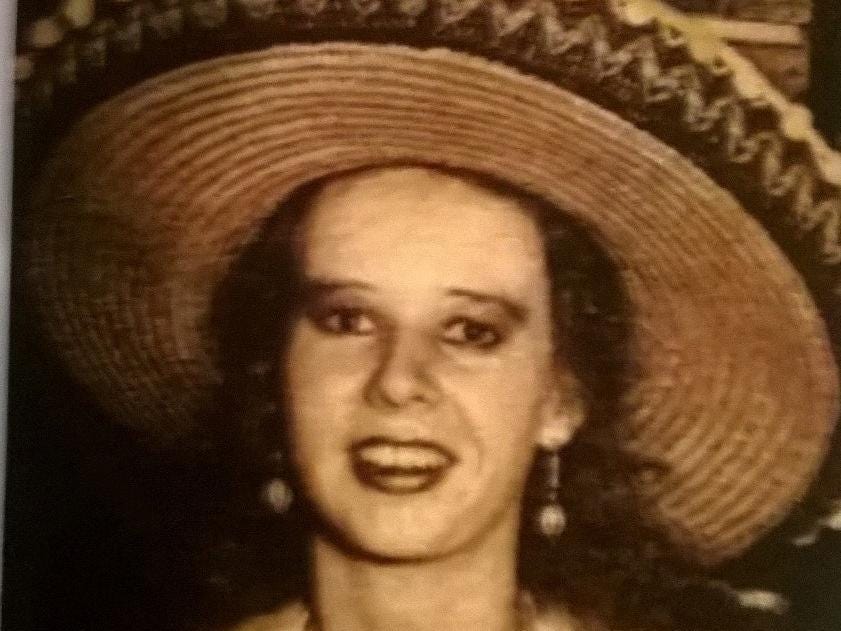

Caroline Ann Hunt

On September 29, 2015, Caroline Ann Hunt, 53 years old, a mother, was found dead in her cell at HMP Foston Hall, Derbyshire. Caroline Ann Hunt was found hanging in her cell. In 2015, four women killed themselves at Foston Hall. In 2015, seven women killed themselves in prisons in England and Wales. In 2016, two women killed themselves in Foston Hall. For the last few years, more and more women prisoners have killed themselves, or better, have been placed in situations where suicide seems like the only available option. Last year, 12 women prisoners are reported to have committed suicide. Does anyone care? Yes. Family, friends, supporters care. Does the State care? Absolutely not. If it did, Caroline Ann Hunt would be alive and even thriving today.

Caroline Ann Hunt had never been arrested. In prison, Caroline Ann Hunt repeatedly talked of suicide, and tried to suffocate herself the night before her death. Fellow prisoners reported their concern. The staff largely ignored both the concerns and protocol, placed her in a single cell, and pretended to monitor her. An inquest that ended this week notes, with great concern, the staff failings. Others note the State failings. Of course, the government says it will do something, but it won’t.

Caroline Ann Hunt’s daughter said, “On 29th September 2015 my mother, Caroline Hunt, passed away aged 53. She was found hanging by a bedsheet in a cell in HMP Foston Hall. Since then my life has been a whirlwind of difficult decisions and emotions. I have learned some very sad truths about life inside prison, and just how difficult prison is for the most vulnerable people in society.

“My mother was a very kind person, who cared deeply for her friends and family members. I believe she was sadly blighted with various mental health issues throughout her lifetime, which led directly to the circumstances surrounding her committing an offence, the first she ever committed. In prison, she felt hopeless and frightened about her future.

“Tragically for my mother, there were many missed opportunities to protect her from the obvious risk she posed to herself, including concerns raised by other prisoners about her risk to herself, and to provide the support she clearly needed. Had the opportunities been taken my mother would probably be here with us all today.

“My mother was the fourth person to die while in custody in HMP Foston Hall in 2015. I hoped that her death would be the last, and no other family would have to go through what I have. I was very saddened to hear that in 2016 a further two women took their lives there: six women in two years who ended their lives. These deaths leave families with endless pain and countless what ifs.”

How many deaths will it take till we know that too many people have died? The State does not care if the tower of cadavers is ten or ten thousand, and, if history is any guide, Caroline Ann Hunt’s story, life and death will soon be forgotten by most of us. This is who we are. We are the citizens and builders of the State of Abandonment. This is how we will be remembered. We all abandoned Caroline Ann Hunt, and we continue to do so, day in and day.

(Photo Credit: Independent / Inquest)