“Starving / Help Now / Millions Are Starving in Bible Lands! …”

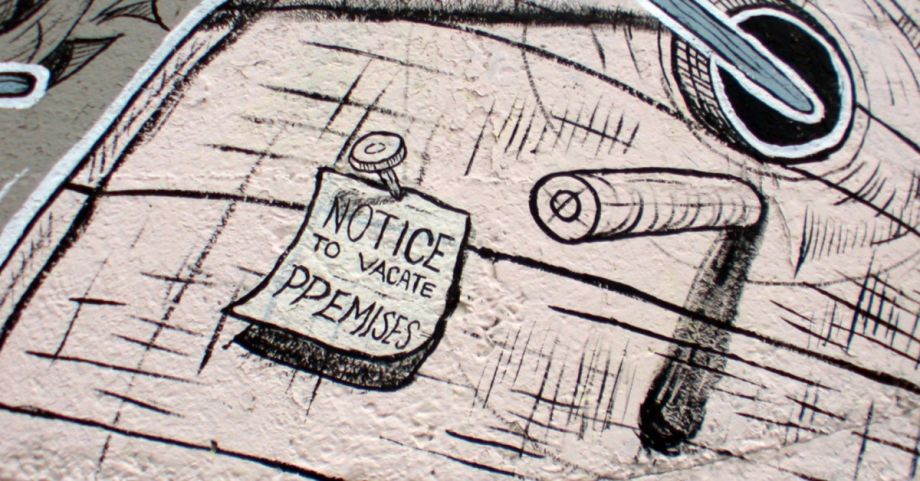

Today’s headline reads: “Anger Over Starvation in Gaza Leaves Israel Increasingly Isolated”. There’s, finally, been much, or some, discussion among “the powers that be” of Israel’s politics of starvation in Gaza. There’s some anger, some dismay, not enough but some. There’s some disgust, some revulsion, not enough but some. As so often, much of this timidity and “modesty” results in an articulation that is actually a blurring of meaning. Starvation is not hunger. Hunger is ”the uneasy or painful sensation caused by want of food; craving appetite. Also: the exhausted condition caused by want of food.” Hunger is bad, destructive, and a politics and public policy based on hunger is evil. But hunger is not starvation. Starvation, and these definitions all come from the Oxford English Dictionary, or better to starve, means “To die, or cause to die”. When starve is a transitive verb, it means “to cause to die”, that is, to kill, to murder, by refusing access to food. That’s what’s going on in Gaza. Nothing else. Starvation.

Does it matter that children are being starved? Yes. Yes, it does. Does it matter that adults are being starved, adults of all genders? Yes. Yes, it does. Is the world acting as if these deaths and this mass murder actually matters? No. Palestinians are not starving to death. They are being starved. That is a death sentence, for the individuals, families, communities, people and nation. What would you call such a public policy?

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image Credit: American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief Artist(s), 1914 – 1918 / Smithsonian Museum)