There is a cause that mirrors the cause of political feminism because it confronts the same principle of disqualification. In Italy, the cause of welcoming with dignity and respect “migrants/refugees” is being vilified by the new extreme right Minister of the Interior Matteo Salvini who has engaged in a war against the most vulnerable women, men, and children who are looking for safety.

The humanist initiative that has taken place in Riace, a small village of Calabria, under the leadership of its mayor Domenico Lucano, in his third term, has been recognized as a model of integration. For this, Lucano became the perfect target for Matteo Salvini, who first had him arrested and placed under house arrest and then deported him away from his villageusing false pretenses of misusing funds and supporting a “business” of immigration.

When Domenico Lucano became mayor in 2004, Riace was on the decline. He had a vision, he imagined an alliance between the local people and the people in need of a place to live. He had plenty of ideas to initiate a different kind of socio-economy that involved community building beyond the usual norms and appearances. His policies revitalized the villagewith the development of a small craft industry with artisanal shops as well as an efficient co-operative waste sorting unit that has been run with migrants for the past 7 years. That was unbearable for the anti-migrant Italian Minister of the Interior. Domenico Lucano proved that a global villagewas possible. His arrest and deportation are part of the global destruction of a sound system of social politics of integration. The goal is to curtail any sort of solidarity, despite that working in cooperation is always more efficient for a more sustainable society.

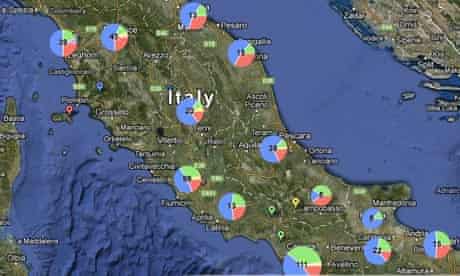

Italy has a new policy: close all human size structures and build huge centers in which to park the refugees/migrants. The Italian government wants to reduce the number of refugees admitted under a humanitarian program which reduced the number of refugees by 60 %. Once again, some people coming from the South are not qualified to be alive, and women are the first ones to be isolated and disqualified.

Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean Sea, the Aquarius, the rescue boat from SOS Mediterranéeis now permanently harbored, missing a flag to navigate. Médecins Sans Frontières announced that it stopped its operation with SOS Mediterranée. The Italian government declared a war against the most vulnerable women men children, the refugees trying to escape the hell of Libya, and further ensured that no country would provide them with the all-important flag. Despite petitions and demonstrations, France, Spain and others did not come to the rescue of the rescue ship.

The resultant reality is death in Mediterranean for people who need the most support for having escaped extreme climate conditions, violence, rape, and for having endured slavery-like situations. Not long ago, the infamous international community was shaken by the image of the slave trade in Libya on CNN. Congratulations went to the work of the journalists who uncovered it, expression of moral outrage burst out in all circles. Where did that outrage go? Where is the outcry as Matteo Salvini degrades our fellow human beings using the rhetoric of migration crisis to lie about the reality of the situation. Matteo Salvini knows no limits. Cruelty is now his official policy.

Last week, the NGO Mission Lifeline accusedFrontexand Eunavforof crimes against humanity and called for the International Criminal Court to investigate the case of 25 migrants drifting without water and food on a dinghy for 11 days, 70 km west of Tripoli, Libya. Nobody moved to rescue them, and the Aquarius was no longer available. In this time of climate urgency, crossing borders is becoming an impossible task for the people the most affected by the policies and actions of rich countries. The dehumanizing populist extreme rights developing in our world institutionalize the criminalization of migrants. Migration is presented as a source of crisis, even though only 3% of human beingson earth migrate. Who needs migration crisis? The mayor of Riace and many others have demonstrated that there is another way. Why are their initiatives being hampered?

(Photo Credit: Twitter / SOS Méditerranée France)