Over two years ago, we wrote about `seclusion rooms’. These are solitary confinement spaces in schools across the United States. More often than not, they’re closets or utility rooms, anything small and tight with a lock on the outside. That is not seclusion. That is torture.

And of course, `of course’, the subjects of this practice are overwhelmingly children living with disabilities. Children like Jonathan King, who, at 13, hanged himself in a Georgia seclusion room. Or the 12-year-old girl living with autism, or the seven-year-old girl living with autism and bipolar disorder.

Or, as described in yesterday’s New York Times, Rose, who, in kindergarten, was locked into seclusion rooms for hours … at five years of age. Her `problem’? Rose had `speech and language delays’. For which she was thrown into a closed, dark space for an hour or so at a time.

Rose’s father reports she was deeply traumatized. The school system, in Lexington, Massachusetts, has agreed, or been forced by a lawsuit settlement, to pay for Rose’s treatment.

Seclusion rooms, screaming rooms, school based solitary confinement can be found in Connecticut, Kentucky, New York, Florida, Ohio. Georgia banned seclusion rooms … `thanks’ to Jonathan King. How many children? How many children must suffer? How many children must then be given `the gift’ of post-traumatic treatment? For how long?

While this issue addresses all children, and all people, it strikes at the heart of citizenship for those living with disabilities. Billions of dollars of profit are generated every year from the care provided for those living with disabilities. Those who care for those living with disabilities are overworked, underpaid, and always under-esteemed. Billions are stolen from their labor and lives.

At the same time that billions of dollars of profit are generated, there isn’t enough money to provide decent, humane treatment? No. This is the production of vulnerability writ large on small bodies. In the United Kingdom, Ellen Clifford, of Disabled People Against the Cuts, DPAC, knows this lesson all too well. In Nigeria, Patience Ogolo, of Advocacy for Women with Disabilities Initiative, AWWDI, does as well. So does Marsha M. Linehan, a psychologist at the University of Washington who, as an adolescent, suffered and barely survived seclusion rooms. Only now, many decades later, can she finally share the stories of her life in the cells.

These women know that the State that treats any group as disposable is worse than a failed or a rogue state. It’s criminal.

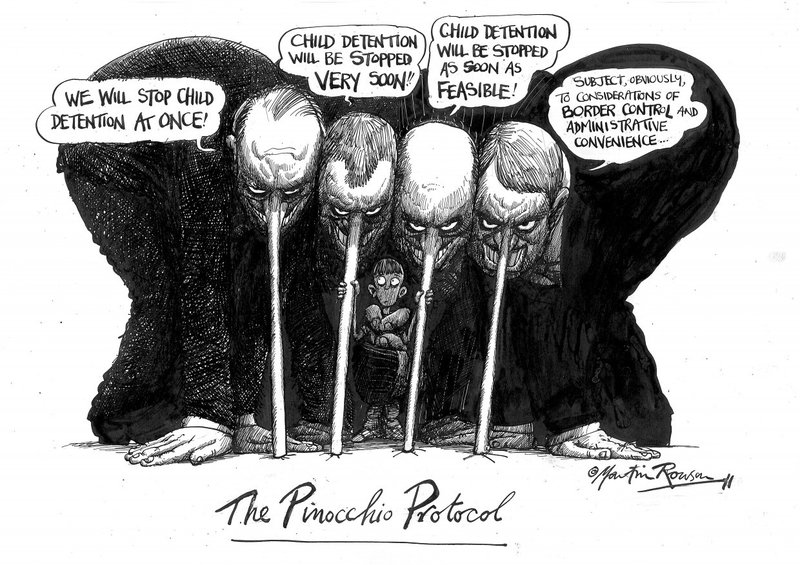

The claim of State poverty as an alibi for physical, emotional and psychological harm against people living with disabilities is a crime. The suggestion that there isn’t enough money or resources is a lie and a crime. And the lie and the crime are framed within a political economy of vulnerability, in which it is presumed that the vulnerable cannot speak or act for themselves.

They can, and they do. And they know that the question of who lives and who dies has been taken over by the question of who lives well and who lives in hell, under constant attack.

End the war on children living with disabilities. End it now.

(Image Credit: Ward Zwart / New York Times)