January 14 will mark the ninth month since more than 300 schoolgirls were abducted from Chibok. At that time, women organized #BringBackOurGirls to break the national and global silence that covered the atrocity. Those women are still organizing, still mobilizing, still demanding action and accountability. Meanwhile, from the national as well as the global community, the silence has intensified. The Chibok women of #BringBackOurGirls warned, from the outset, that failing to act meant the violence, terror and horror would escalate and expand. This week, their prophecies came to horrible fruition.

Over the past week, Boko Haram is reported to have attacked and razed 16 villages. Baga has been emptied. Many were killed. Others fled to Chad. Many of those who fled drowned in their attempts to cross Lake Chad. Amnesty reports this as “Boko Haram’s deadliest act” thus far. According to survivors, women, children, elders and the disabled were the principal targets. They were hunted as they fled. Now, the landscape is littered with their dead bodies, burnt homes and abandoned villages. The bodies pile up, too many to bury.

Over the weekend, in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state, a girl, some say she was ten years old, walked into a busy market. A bomb, strapped to her waist, exploded, killing many, wounding many more. The girl was torn into two halves.

Some say using a child so young is a new phase. It’s not. The schoolgirls of Chibok are the girl-child of Maiduguri. The line is direct. The women of #BringBackOurGirls said so, nine months ago, and no one listened. Will anyone listen now?

Bring back the hundreds; bring back the thousands; bring back the one. #BringBack #BringBackOurGirls #BringBackChibok #BringBackBaga #BringBackMaduguri #BringBackOurGirls #BringBackOurGirls #BringBack

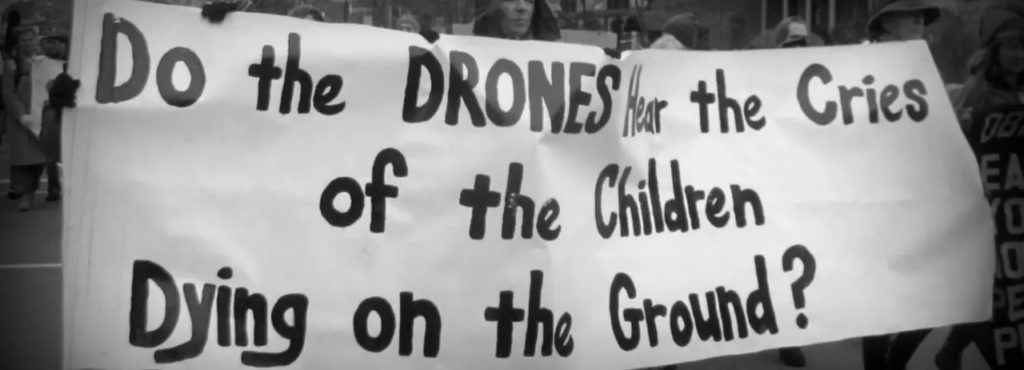

(Photo Credit: Premium Times)