As one who was an activist and a radical pre-occupy (as I have been during- and will be post-), I had mixed feelings upon occupy’s initial momentum. It is nice to be surprised once in a while. A friend put it best—“if someone had told you five years ago that Adbusters would be responsible for the next US protest movement, and that Crimethinc would be providing useful, levelheaded discourse on it, would you have believed them?” Not a chance. So when it kicked off, I was extremely skeptical. I had long ago dismissed anything resembling a mass mobilization as being unable to enact real change in the USA. Instead, I cast my lot (as did many of my friends and colleagues) with what we call somewhat euphemistically “long term movement building”: direct services, raising funds and resources for said direct services, and small-scale community building. But I was also excited that the national conversation was approaching a critique of capitalism, excited for there to be a left movement in the USA again, and intrigued by the possibilities of the encampment tactic. Occupy’s connection to the “Arab Spring” in the national imagination gave it a particularly tantalizing flavor of possibility.

On paper, occupy is inherently aligned with feminist critiques of power. The heart of occupy is an objection to unearned power—the same objection at the heart of work seeking to dismantle patriarchy, white supremacy, homophobia, ableism, and the myriad interlocking oppressions that both sustain the ruling order (or in the parlance of occupy, the 1%) and keep the 99% divided and conquered.

But at large and locally, the internal and external dynamics of the movement have not always reflected that ideological alignment which seems at once so obvious and so necessary. Instead, the physical spaces of occupy have often replicated oppressive social relationships, when they should have been sanctuaries for those who need it the most—people experiencing homelessness, people of color, queer and trans* people, women in need of shelter and childcare, and survivors of violence, to name a few. Also, the conversation with occupy seems to have shifted to mainstream liberal concerns such as Citizens United and away from poverty and structural violence.

Occupy’s shift to liberal values, if not tactics, did not come as a total surprise. Radicals have long known to be wary of our liberal and moderate compatriots. They can sometimes be our worst enemy or biggest obstacle, as The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. so eloquently expressed in “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”:

…the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom…lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

This is why a feminist critique is essential to occupy. We have got to keep an eye on the people who claim to be speaking for us or on our behalf, but are not. It is not a lack of demands or incoherence of message that weakens the occupy movement, but the lack of a radical analysis, and the unwillingness of privileged people within the movement to step back and let the movement be directed by the needs of its most marginalized participants.

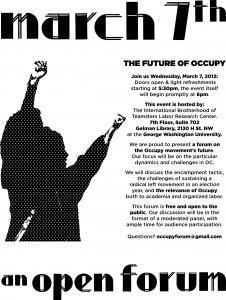

For a moderated panel discussion of this and more—where is occupy going in relation to labor? To academia?—please attend a Panel Discussion on the Future of Occupy, GWU Gelman Library, Wed March 7

(Photo Credit: Rabble)