Organizing one-on-one works, but what is one-on-one organizing? In fact, what is a one-on-one? A one-on-one is a conversation that one person schedules with one other person in an organizing context. 30 minutes to an hour, in the other person’s home, a coffee shop, etc. The Midwest Academy defines six parts of a one-on-one:

- Be Prepared: Think about what you know about the person, run through the next five steps. Take some notes. Call/text to confirm–getting stood up sucks.

- Legitimize Yourself: A one-on-one flips the script. After some casual conversation, set the tone that this isn’t just two people hanging out.

If you don’t know them: “Thank you so much for taking time today. As I said on the phone, I’m Anne and I’ve lived in Louisville since 2013 working with faith congregations. Recently, I’ve been meeting with folks to talk about our personal experiences with healthcare, especially with all the changes coming. I had a great talk with [mutual friend] Donna last week, and she suggested I talk to you because you’ve been a nurse. I’d love to hear about how you decided to become a nurse!”

If you know them: “I know this is different from our usual thing, but I was really shaken up by the election, especially with my health and the healthcare changes coming. So I’m talking to friends like you who are affected, too, about what’s going on and what we’re doing next. So, how are you holding up?”

- Listen: “Draw people out, identify their self-interest, clarify their concerns, establish rapport. If you are whizzing along telling your story, you won’t be able to do any of this.” –Midwest Academy.

Ask why questions, ask for stories, share of yourself (⅓ sharing, ⅔ listening). Pay attention to what motivates them: their “self-interest.” Here are four categories of self-interest:

“I want,” what they want/don’t want for a good quality of life: “I have 60K in student loans.” “My mom has Alzheimer’s and it’s been hard.” “I don’t feel safe when I walk home at night.”

“I believe,” a value that drives them: “Everyone deserves a second chance.” “God calls me to love my neighbor.” (Ask: Where does that belief come from?)

“I am/want to be,” an identity: “I’m a leader,” “I’m someone people can count on” (You may infer this. If they told 8 stories about their kids, is being a parent is an important identity? Yep!)

“I love/respect,” a key relationship: family, a group, a role model

- Agitate: Many people won’t describe their feelings about a sick parent as anger. But should they feel angry if their parent lives in a nursing home with crappy facilities because the good facilities cost too much? Yes! Here’s your job:

- Connect those self-interests, the way they want the world to be: (I want to be debt-free, I want everyone to have a second-chance, I want to be independent, I want my kids to be okay)

- …with all the things in the world that purposely make that hard: (student loan companies, the prison system, not getting paid enough, unsafe schools, etc.)

- Get a Commitment: So, here’s what we’ve learned:

- We want things.

- Systems are set up to make getting those things hard, and we’re angry about that.

- What now? Let’s go home feeling fatalistic! Nope.

This is the moment of hope! “This problem is real. It hurts both of us. So we’re going to solve it. Here’s the first step: are you in?” Join a committee, come to an action, get together Saturday to plan next steps. (Have an ask in mind ahead of time!)

- Follow-Up: Call them, remind them about the next thing, check in on how they’re doing. Encouraging people to share their pain, connecting it to a giant system of exploitation, promising them that you’ll fight together to end it, and never calling back is a shitty thing to do.

That’s the outline. Getting good means practicing. I have a great job that makes me do 10 a week and I still have surface-level one-on-ones. I still chicken out on asks. But I’m way better than I used to be. So here’s my advice: pick 5 interesting people and do a one-on-one with them, and go from there.

There is nothing in the one-on-one outline about privilege. White people, men, cis people, etc. have privilege. But organizing around privilege is lower-hanging fruit organizing. If we help a white person recognize the extent of their privilege, they will feel guilt that may push them out the door to a protest, or to their checkbook, to the verses in Scripture about feeding the hungry. All of these actions are good.

Real higher-hanging fruit organizing pushes people who already see themselves as privileged to see themselves as harmed. This works whether they articulate privilege by saying “I benefit from the harmful forces of white supremacy,” “I’m #blessed,” “I pulled myself up by my bootstraps,” or “I am white and proud.”

It starts with agitation! What do you want your life to look like; what systems are stopping you right now? A bad healthcare system? A culture that teaches you to be afraid of people of color all the time? The privilege conversation doesn’t allow room to say what you want. Only when you do that do you recognize how comparatively little you give up when you check your privilege and enter into movement work.

To have good relationships with Black leaders here in Louisville, I have to give up some privileges that I really like, like dominating meetings and bossing people around. But that’s peanuts compared to what I gain: relationships that reflect my values and who I want to be–a friend and support, not a white lady on the bus clutching her purse.

If acknowledging privilege pushes us to read the world differently, good agitation pushes us to imagine the world anew: to envision what we, individually and collectively, want our lives to look like. It doesn’t encourage guilt. It doesn’t encourage racism and scapegoating. It encourages anger: anger at systems, not people of color.

Guilt fades, anger doesn’t. Here’s how to get to anger: admit that you want your life to be different. Admit that you want your mother not to have Alzheimer’s. Admit that you want to feel more when you walk into church on Sunday. Admit that you want respect. Look hard at what system stands in your way. Start there.

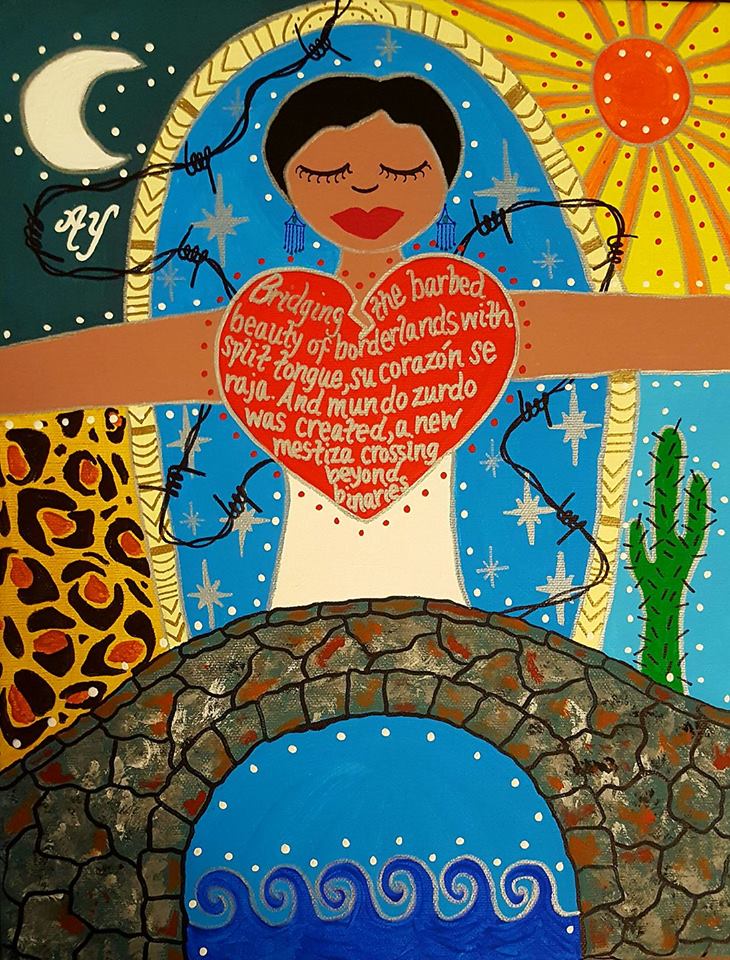

(Photo Credit: Resilience Circles)