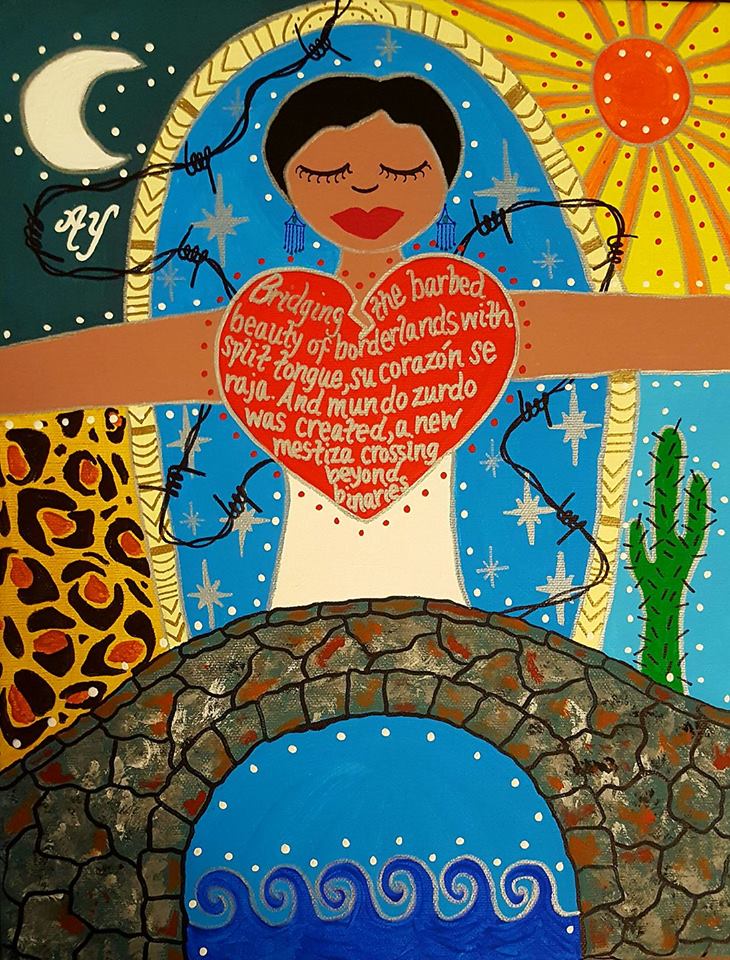

“The act of ‘falling in love’ can serve as a ‘conduit’ or impetus for the action necessary to challenge oppression.”

-Chela Sandoval, paraphrasd by Maythee Rojas

As borders are not separated from all of us who construct them, the cracks in the borders do not merely take off a weight so that we can breathe more easily. When we see each other in new ways, we, too, shift: our convictions are tested, our lived experiences are re-interpreted, and we are confronted by the fear and promise of transformation.

To talk about the borders is to talk about fear. To talk about responsibility or liberation or love is to talk about fear. Even in the supremely brave act of love, we fear that every word can be misinterpreted, every action misguided, every relationship threatened by the realities of our bordered lives.

Thus, we must respond to this fear in “the language of lovers [,which] can puncture through the everyday narratives that tie us to social time and space.” We can write the borders in the language of our own stories. We can challenge the borders out of responsibility to and love for one another. And we, ourselves, can shift.

The language of love represents a radical change from the language of the everyday, for it challenges the comfort of our abstract principles, the familiarity of our homes, and the constancy of our very selves. It throws us into relationships that force us to confront our privilege and our prejudice, our fears and our doubts. It calls us to “de- and re-center,” to be transformed by one another, to find a home amid all manner of shifts.

To create a home in our bordered world is to live each day with the inescapable realities of separation and oppression and to be called every day to common struggle. Our feminist struggle is not common in the sense that the oppression we face or the liberation we envision is the same. It is common through our dedication, first and foremost, to one other.

After a night at Occupy Wall Street, Manissa McCleave Maharawal “biked home over the Brooklyn Bridge and I somehow felt like the world was, just maybe, at least in that moment, mine, as well as everyone dear to me and everyone who needed and wanted more from the world. I somehow felt like maybe the world could be all of ours.”

Love imagines that possibility; that the world does not belong to an intangible universal but is home to all of us, sharing our stories, challenging our borders, and bravely committed to the responsibility and the joy of loving one another.

(Photo Credit: Racialicious)