Being a woman today is marked by violence.

On New Year’s Eve in Cologne, on a square between the cathedral and the train station, about 200 women were sexually assaulted and robbed after about thousand men circled them to isolate them from the rest of the crowd. This type of assault has been reported else where in Europe: Helsinki, Zurich, and others. It has also occurred in Cairo and Tunis.

On Tahrir Square in Egypt, in 2013, during demonstrations against the government, women who were present wielding their right to be in public spaces would be circled by hundreds of men and then undressed and raped. These attacks were constant. Women and men organized and formed groups wearing fluorescent yellow jackets and helmets, to liberate the women under attack. They knew that they could not rely on the authorities or the police. The military government also used violence against women.

The same occurred in Tunisia when women took to the streets of Tunis in support of a positive transformation of the society. Since then, they have been organizing and fighting to defend their rights to public spaces.

This violence belongs to a trend that has been ignored for too long. In Cologne, the police did not intervene right away despite the system of video surveillance that is part of the globalized economies with their security market. The assaults were publicly reported only five or six days after the fact.

The fact that in Cologne most of the aggressors were North Africans and/or asylum seekers blurred the big picture and fueled resentment against immigrants and refugees, thereby encouraging racist violence. German feminists have responded: no excuse for sexual predators or for racists. Other European feminists have simplistically associated this event with the rise of fundamentalist Islam.

That presentation is limited and ignores the globalized neoliberal economy’s reliance on various strains of neo-conservatism and religious fundamentalism including Islamic fundamentalism to increase its hold on society.

One could remember, how in 1936, the phalanges, Franco supporters, whose slogan was “viva la muerte” dispersed their cruelty against women and men. They violently commanded women to stay away from public spaces, to reproduce and take care of the household. All of that was supported and encouraged by capitalists.

Clearly, women’s emancipation is one of the biggest stakes of an oppressive society.

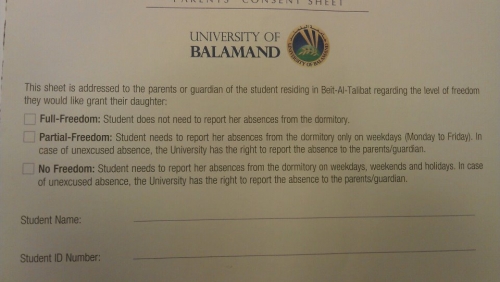

Today, the European militarization of its borders along with austerity measures within the context of fear of “terrorism” opens the temptation of a constant state of emergency. The ordeal of women in migration facing infinite sexual violence and death during their journey is rendered invisible. What is left is the growing rhetoric for more policing and more appearance-based prejudices, which allow security markets to develop. The current paradoxical protective and aggressive discourse of the authorities puts some women under surveillance, hidden behind security forces and at the same time normalizes the position of other women as victims of sexual violence, according to race and geographical locations and conflicts.

Similarly women’s reproductive bodies, again racially defined, are under surveillance in the United States, with the incarceration of women for miscarrying or having an abortion where it is more and more difficult to get one. These signs of patriarchal essence that justifies violence against women correlate with the expansion of the neoliberal economic order that disadvantages women and minorities and throws them into precarious situations, again rendered largely invisible.

The code of silence that covers the attacks against women in Europe is troubling. In France, a recent study on sexual harassment in public transportation revealed that 100% of the women’s answers indicated various levels of harassment. Generally in Europe sexual assaults have been reported around football games, and other public events. In Cologne few days ago, a journalist of the Belgian RTBF was reporting on the beginning of Carnival and the security measures to protect women participants, when a group of white men sexually assaulted her, all this in front of the cameras.

Without a broader transnational understanding of the causes for the regression of women’s social and political right to be in public spaces, the prospect for better women’s social and political equality with men are slim.

A large transnational solidarity movement, beyond judgment, must be the force against the current trend of violence against women, the basis of all violence that is fueled by the devastating unfettered market forces that consume bodies.

(Image Credit 1: Osez le féminisme 69) (Image Credit 2: Osez le féminisme)