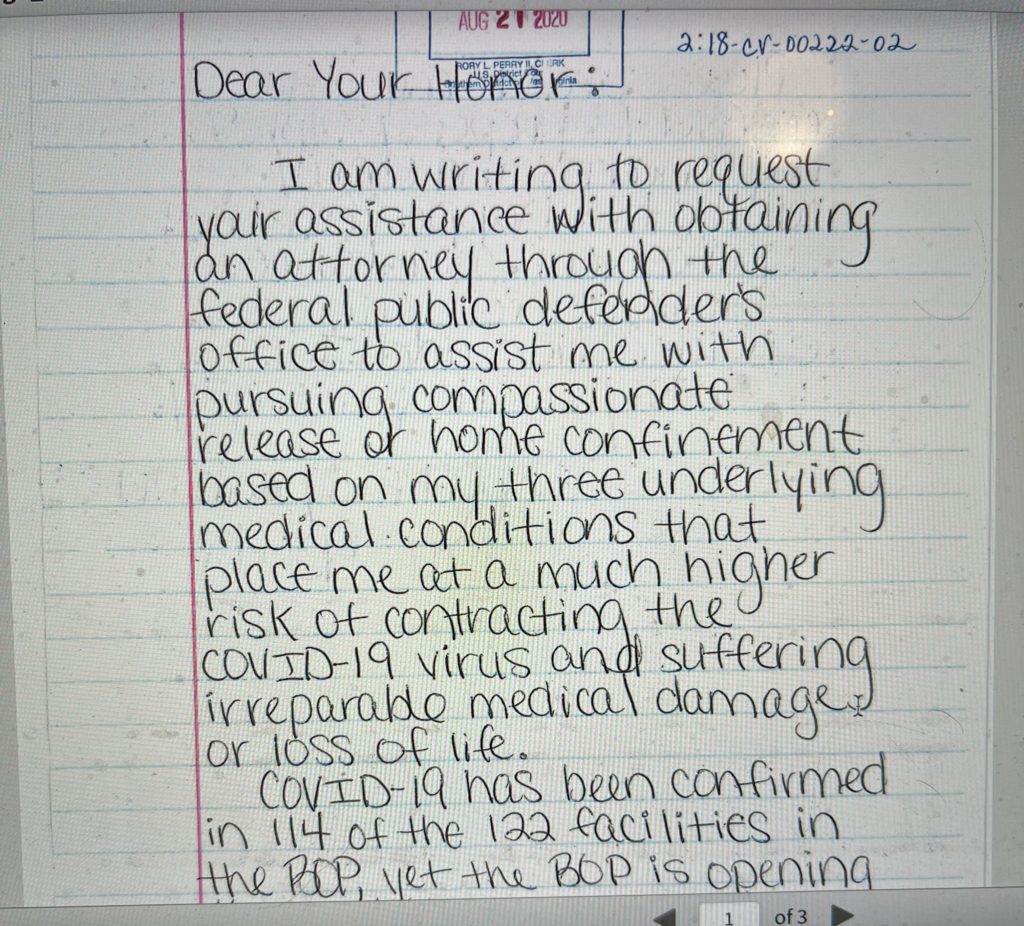

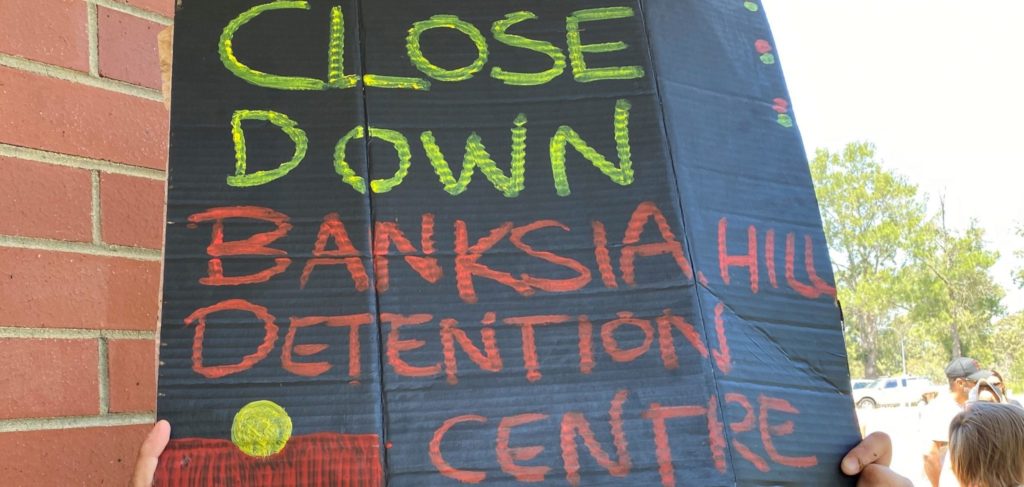

Today’s headlines read: “The juvenile prison where child was ‘treated like an animal’ gets funding boost”; “Banksia Hill juvenile detention centre gets $25 million to address ‘dehumanising’ conditions, cut incarceration rates”. Banksia Hill Detention Center is in Western Australia. It’s the only juvenile detention center in Australia that houses both males and females. The situation is so bad that, in January, Perth Children’s Court president Hylton Quail sentenced a 17-year-old child to Hakea Prison, an adult prison, rather than send to Banksia Hill. Hakea Prison is where 22-year-old Noongar man Ricky Lee Cound was kept in solitary and denied clearly needed medical care. On Friday, March 25, Ricky Lee Cound died. After weeks of self-harm and institutional refusal, Ricky Lee Cound died in a place that is preferable to Banksia Hill Detention Center, and today, Banksia Hill Detention Center received $25 million to improve its conditions. Don’t improve it. Shut it down.

In February, the same Judge Quail was presented with the case of a 15-year-old child. The boy had been held in Banksia Hill for 98 days. For 79 of the 98 days, the boy was held in what the judge called a “fishbowl” cell, where he had no privacy whatsoever. The judge described the exercise yard as a “10 x 20 metre cage”. For 33 of the 79 days, the boy wasn’t allowed outside the cell at all. The judge rightly called this “solitary confinement”. The boy received no education while in custody. The boy threatened self-harm and attacked staff. In fact, he was standing before the judge because he had attacked staff and damaged state property. Judge Quail responded to the situation, “When you treat a damaged child like an animal, they will behave like an animal. When you want to make a monster, this is how you do it.”

Today, Banksia Hill Detention Center received $25 million to address these conditions. Don’t address, don’t improve. Shut it down and build real alternatives.

The problems at Banksia Hill Detention Center go way back, continue to the present, and are hard baked into its design and purpose. According to the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services’ 2020 Inspection of Banksia Hill Detention Center, “Aboriginal young people continue to be overrepresented at Banksia Hill, making up 74 percent of the population.” Even by Australian standards, where Indigenous young people typically make up 49% of those “under youth justice supervision”, 74% is high … and catastrophic.

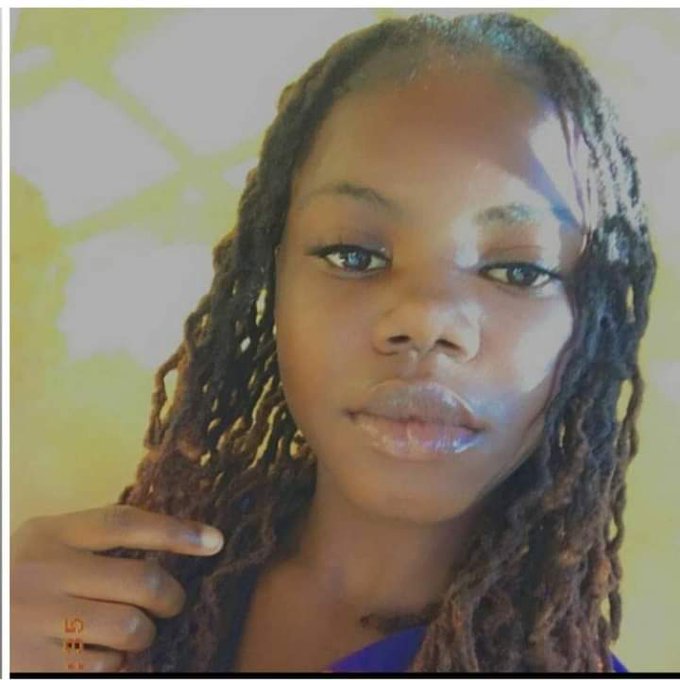

And for girls, it’s especially bad. 80% of the girls are Aboriginal, a mix of sentenced and remand. While services for the girls had improved since the last inspection, the report notes that the improvement came from individual staff members, and not from any strategic or management plan. That means when the staff moves on, and they do move quite a bit, there’s no guarantee the improved services will remain. Further, a number of staff make it known, to the girls, that they don’t want to work in the female section. While girls form a minority of Banksia Hill residents, their numbers have been increasing, during a period where the general population has been decreasing. From 2017 to 2020, the numbers of girls generally doubled. Likewise, where they were 6% of the Banksia Hill population in 2017, by 2020, they comprised 13%. And yet, with all that increase, everything involving girls at Banksia Hill Detention Center was ad hoc.

Banksia Hill Detention Center has been open since 1997. It has gone through repeated cycles of “major redevelopment”, to no avail. That’s because the improvements, despite individual staff members’ best intentions or lack thereof of, were never meant to improve the lives of Aboriginal children. Don’t `improve’ the institution, yet again, with a fat purse. The children housed in Banksia Hill Detention have problems, but they themselves are not the problem. Shut it down. Build real justice by investing in real care.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: National Indigenous Times)