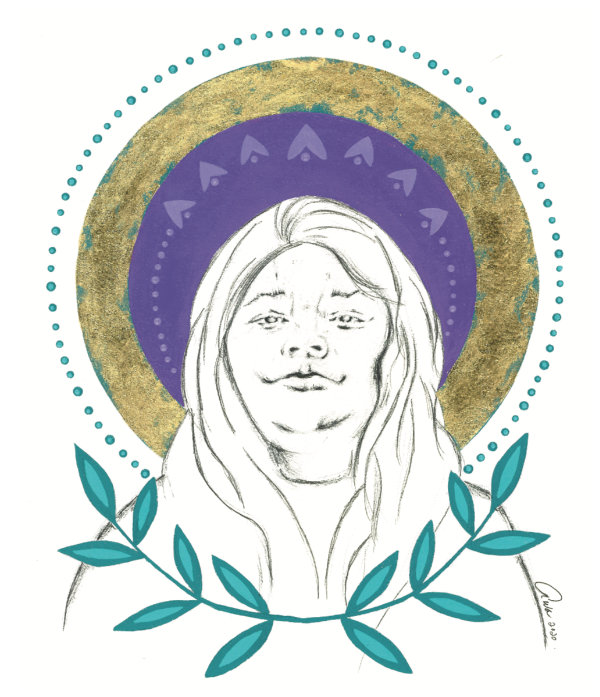

I support Joyce’s Principle

On September 28, 2020, Joyce Echaquan — mother of seven, partner to Carol Dube, member of the Atikamekw nation of Manwan, 37 years old – died … or, better, was tortured to death, while lying in a hospital bed in Joliette, in Quebec, Canada. On September 26, suffering severe stomach pains, Joyce Echaquan checked herself into a hospital. On September 28, as her pain worsened, nurses administered morphine, even though Joyce Echaquan told them she was allergic to morphine and that she had a pacemaker. As Joyce Echaquan screamed in intensifying pain, the nurses told her, “You’re as stupid as hell”; “Are you done acting stupid? Are you done?”; “You made some bad choices, my dear. What are your children going to think, seeing you like this?”; “She’s good at having sex, more than anything else”. We know this because Joyce Echaquan, in excruciating pain, dying, pulled out her phone, started filming and posting on Facebook. The video is a bit over seven minutes long. Soon after Joyce Echaquan died, or, better, succumbed to torture. There was a brief `outcry’ in Canada at the treatment Joyce Echaquan received, which was perfectly ordinary treatment for Indigenous women.

Joyce Echaquan pulled out her phone because she knew. She knew because it had happened before to her. She knew because she was an Atikamekw woman. She knew because. Period. She knew that her family would organize and protest, decrying systemic racism. She knew they would hold her in their hearts and souls. She knew as well that the government of Quebec and Canada would deplore the horrible act, would demand an investigation, and ultimately would do absolutely nothing.

There was an inquest, which found that systemic racism played a key role in Joyce Echaquan’s death. The Quebec government promised it would do something. It did. It refused to adopt “Joyce’s Principle”, policies aimed at providing fair access to health services for Indigenous people, and it stopped discussion of Joyce’s Principle at the national level. Why? Because Joyce’s Principle includes discussion of systemic racism. The Atikamekw Nation is protesting and pushing for adoption of Joyce’s Principle, as a first step.

Meanwhile, the press continues to cover Quebec’s position as “failure”: “Quebec has failed to deliver on its promise that it would enshrine in the law the principle of cultural safety for Indigenous communities.” Quebec did not fail, it refused. It said, explicitly, there is no systemic racism in its health care system, and any mention thereof will be cut off, with the same brutal and racist efficiency that was applied to Joyce Echaquan. Where there is no attempt, there is no failure. Where an action is part of ongoing public policy, there is no failure. There is refusal. Period. Calling it by another name provides the torture, and the torturers, with alibi. Joyce Echaquan deserved, and deserves, better.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image credit 1: Eruoma Awashish / Joyce’s Principle) (Image credit 2: Ernest “Aness” Dominique / canadianart)

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2020/10/01/this-treatment-is-not-unique-to-joyce-indigenous-medical-workers-say-joyce-echaquans-death-is-the-latest-tragic-symptom-of-a-longstanding-health-care-crisis/justice_for_joyce_vigil.jpg)