Around April 10, 2020, it became all too clear that the UK Government had been advancing a faulty set of numbers concerning the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the population. Over the following week, it would backtrack, confess shortcomings, and curiously ‘discover’ that very old administrative and statistical procedures had not been factored into the death total numbers. The biopolitical crux of the problem was that, while deaths in hospital due to C-19 were being daily reported by the massively under-funded and austerity starved NHS, deaths out ‘in the public’ were being reported once a week and not being factored into the daily totals. Which meant that anywhere from 10-50% of C-19 deaths around the UK were not being reported or integrated into overall figures.

The revelation of this bureaucratic glitch came as a bit of a shock to most people, as the mortality numbers for the UK were already grim, and well on track to match the numbers in Italy and Spain, European countries particularly hard it by the virus. But wait! Britons are not in the EU! “We gained our Independence from Europe with blessed Brexit!” Oh, wait, that’s right, viruses give fuck all for national borders, and nationalism. Even Boris, that prevaricating, racist side-kick showman who helped to gut the NHS and slash doctor and nurse salaries (he led the cheers in Parliament on the day the Tories won that vote)–even bouncy Boris had to admit that it was the NHS that saved his life, in particular two nurses, one from Portugal and the other from New Zealand.

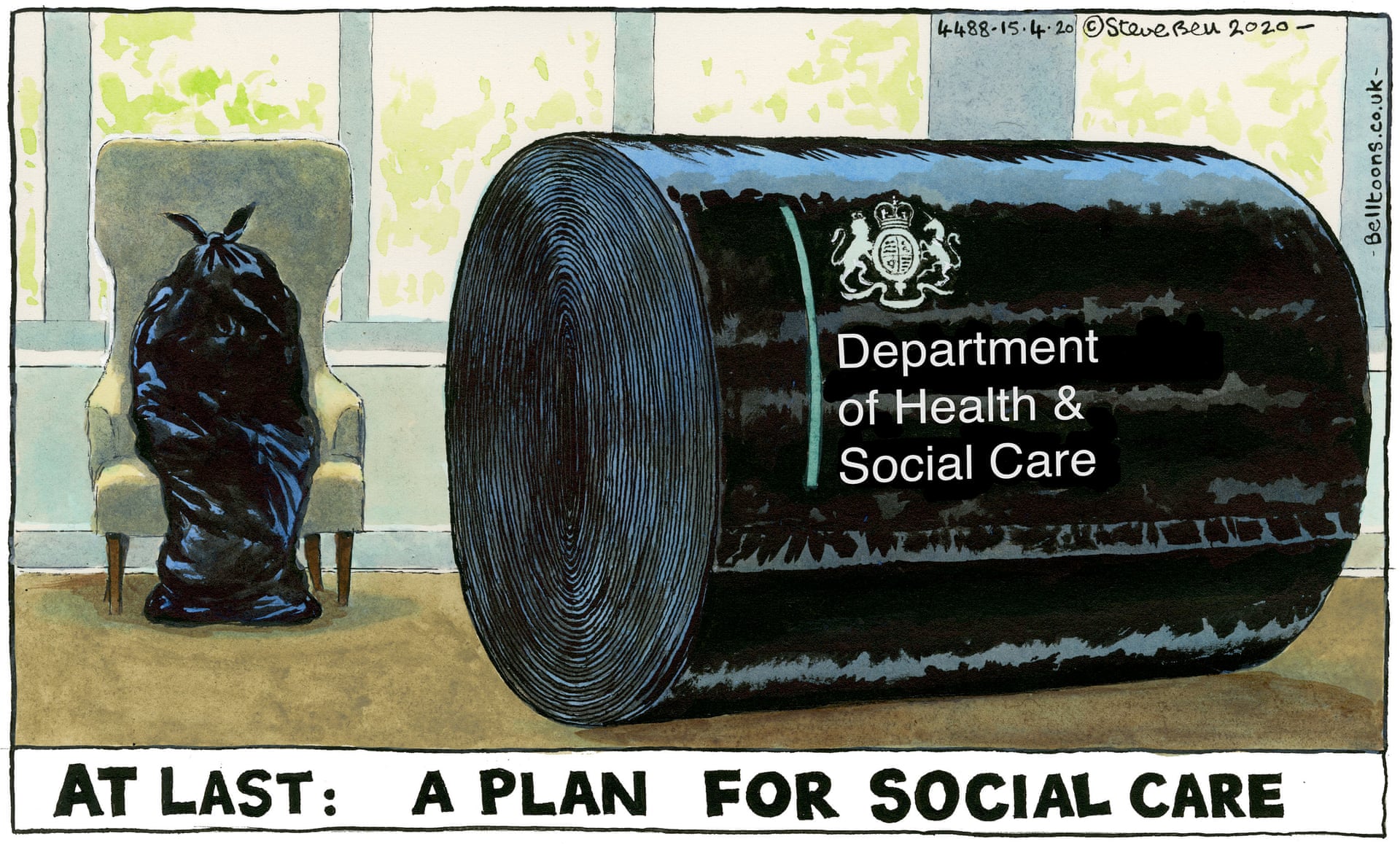

Many people in the UK just slightly older than the clown PM were not so lucky, as the many people who could have been saved if he and his government had acted swiftly and with care and solidarity with the most vulnerable perished needlessly. But today around 80% of the UK’s nursing homes and elderly care facilities have reported infections, and the death toll for these elders is rising sharply. On April 14th, the Financial Times published a piece that outlined the coming horror: “Britain’s care homes are struggling to cope with a wave of [C-19] cases, with thousands of residents at risk of dying as the disease spreads. Operators say official figures misrepresent the extent of the critis and complain that they are short of protective equipment.” The article noted that around 400,000 older people currently live in UK care homes, and up to two-thirds of the facilities are reporting that elderly and frail residents have contracted the infection.

Statistical modelling–dodgy at the best of times, seriously flawed in the case of the UK’s mortality numbers–optimistically suggest that around a quarter of this elderly population, that is around 100,000 people, could die if C-19 ‘becomes endemic in care facilities’. But it is clear these are not real numbers, and the statistics we have for actual deaths are not real numbers precisely because of how the statistics are compiled. Coupled with the lack of resources and protective equipment for front-line workers, the situation in the UK continues to be very serious. As of today (April 16), while Boris continues to convalesce at his Chequers residence, the UK is reporting more daily deaths than either Spain or Italy. Of course, it is easy to say that this world health crisis could have been handled better, and that should be said and also strongly debated in parliament. But what is harder to grasp, very difficult to model, and easy to manipulate in populist talking points, is the long-term effects of austerity on a society structured in different kinds of racial, class, social, embodied, and regional domination. The numbers of front-line staff dying of C-19 are disproportionately people of colour…

I write this from northeast London, in lockdown now for three more weeks, in a working class and diverse neighbourhood of people of colour, where the government’s inaction and, specifically, Boris’s absurd bravado (a small nasty shadow against Trump’s looming idiocy) has put fear in people’s eyes, and (sometimes racist) anger in their distancing. Well, at least capitalism has been put on a kind of hold for a couple of months; we’ve all gotten a taste of what it would mean to overthrow it.

(Image Credit: Steve Bell / The Guardian)