Recently, Bolivia’s newly appointed vice president, David Choquehuanca, delivered a speech in the National Assembly of another type. He talked of the culture of life, interrelations between all beings, the Pachamama, and the cosmos. He spoke of harmony with Mother Earth. He also reminded the audience that the way of life and the understanding of indigenous peoples’ world vilified by the colonial power to allow their extermination. Still, as David Choquehuanca asserted, they have never strayed.

He mixed in his speech indigenous words such as Ayllu that is an organizational system of all beings, all that exists and all should flow in harmony on our planet. The savvy and intelligent blend of genres unwraps a different perspective on our limited, violent world.

His speech was premised on indigenous baselines, which also implied a particular vision of the sacred role. Moreover, his words reminded the struggle against “all form of subjugation against colonial thoughts, against patriarchal thoughts…”

He insisted on the nature of this power that distorts the minds of politicians. How did it come to be?

Far too many westerners like to believe that they control all things; in fact, the encumbered pattern that accompanies this belief tends to force upon other people what will work to their own interest. They have been worshiping their civilization, foisting this power relationship on others to worship it, to the point of absence of sight for its disharmony. The shock of civilization has another side!

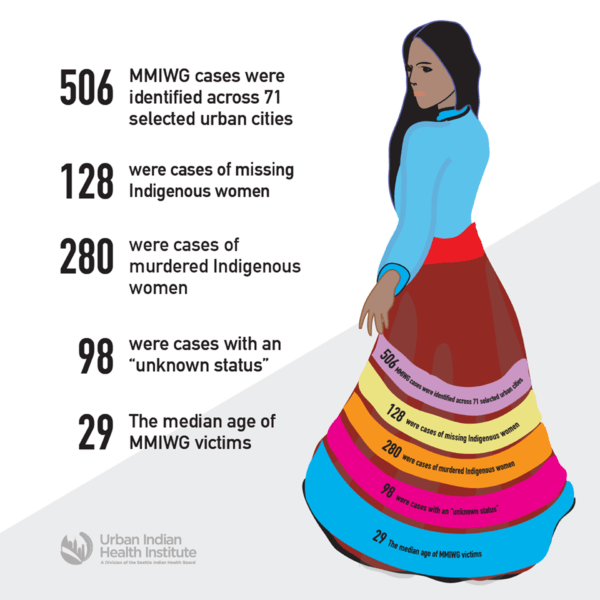

The “heartless” people in charge of state affairs in the United States during the past four years with all the extravagances of their commander in chief trampled all humane ethics, rights, and intelligence of life. But they were the pure product of this disharmonious civilization. American Indians have mobilized in significant number in Arizona to reverse the usual conservative claim of the state. But their votes were not even labeled as Native American votes as Jodi Archambault, a citizen of Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, remarked, they were called “something else” on the CNN infographic. Native Americans are rendered invisible as the history of the bloodshed that built the United States, remarked Archambault.

Invisible again, the fight for respect of the Shinnecock of New York state, as their land and way of life, including their fisheries, are always compromised by the State. They created Sovereignty Camp 2020 to remind the State and its inhabitants that they were a real nation.

American Indian women of the United States have led the fight against the whites’ nefarious plans to exploit them and their land, consequently, Mother Earth, and to eliminate their way of life from the picture of life itself. Native Americans, women, and men have been at the forefront of climate and environmental fights. Water is life, they shouted. They formed squads of water protectors, for protection of life. They organized ceremonies and fought and won legally.

We see now the resurgence of the smallpox contamination strategy. As a reminder, white settlers gave smallpox contaminated blankets to American Indians in the 18th century. Only this time, it has taken a different form. Covid 19 didn’t affect the reservations during the first wave as much as it is doing now. Tribal power has tried to isolate the reservations to protect their populations with the highest rate of underlying conditions. The Navajo nation is also talking about their elders’ weakening conditions due to the wanton uranium mining, leaving contaminated waters for Native American communities. They observe in many reservations the highest rate of contamination and deaths, killing the elders who are the teachers for the young generation. They are afraid of losing the heart of their language in the process. The land is to be seized. The strategy is always the same, isolate and create a series of rationales to put hassles for these communities. The colonial power is still looming over the indigenous populations.

The neoliberal profit-making political climate has not admitted the nature of this equilibrium that David Choquehuanca described in his speech. The harmony is disharmony; life is a series of crises. The feminine is removed from the public sphere and left to exploitation and violence in the process, and in whole so is the Earth. There is a part of politics only concerned with masculinized images of technology, financial power, and progress as soul saviors, to let the ugly happening. It is this ugliness that Bolivia’s Vice President identified and provoked with the people heritage and cultural power to call for deep transformation of power with the Bolivian State which should be a lesson for all of us.

(Photo Credit: Sandro Cenni / Medium) (Image Credit: Jordan Singh / Twitter)