On Tuesday, November 8, Americans go to the polls. That’s the story line, but a river of disenfranchisement runs through those elections, and in some states, that river is a lake, if not ocean. Across the United States, over 6 million United States citizens are barred from voting because of “felony disenfranchisement”, laws that forever restrict voting rights for those who have ever been convicted of felony-level crimes. The good news is that more people are aware of this injustice, and, in states like Virginia and Maryland, governments or, in the case of Virginia, a governor is doing something about that. The bad news is a bit more voluminous: The numbers of felony disenfranchised have risen precipitously and steadily over the last few decades. 1 in 40 adults, or 2.5 of the total voting age population is currently barred from voting due to felony disenfranchisement. One in 13 African Americans of voting age is disenfranchised. Black Lives Matter. Black Voters Matter, too. Felony disenfranchisement has been a war on Black and Brown communities, and it has targeted women of color particularly.

Like all wars, this war has its special geographies. In Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia, more than 7 percent of the adult population is disenfranchised. Florida alone accounts for 27 percent of the disenfranchised population nationally. In Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, more than one in five African Americans is disenfranchised.

Eight states deny voting rights more or less permanently: Alabama, Arizona, Delaware, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nevada, Tennessee. Arizona permanently disenfranchises persons with two or more felony convictions. Mississippi permanently disenfranchises persons convicted of certain felonies. In Delaware people convicted of murder, bribery, and sexual offenses are permanently disenfranchised.

Iowa presents a particularly painful theater of cruelty. In 2005, Governor Tom Vilsack restored voting rights to those who had completed their sentences via executive order on July 4, 2005. In 2011, Governor Terry Branstad reversed the executive order and returned many to permanent disenfranchisement.

In 2015, in Kentucky, Governor Steve Beshear restored voting rights to individuals with former non-violent felony convictions via executive order. Later in 2015, when Governor Matt Bevin took office, he reversed this executive order.

Tennessee offers an entire menu of options for disenfranchisement. Those convicted of certain felonies since 1981 and those convicted of certain felonies prior to 1973 are permanently disenfranchised.

Nevada disenfranchises anyone convicted of one or more violent felonies and anyone convicted of two or more felonies of any type. In Nevada, two strikes and you’re out … for good.

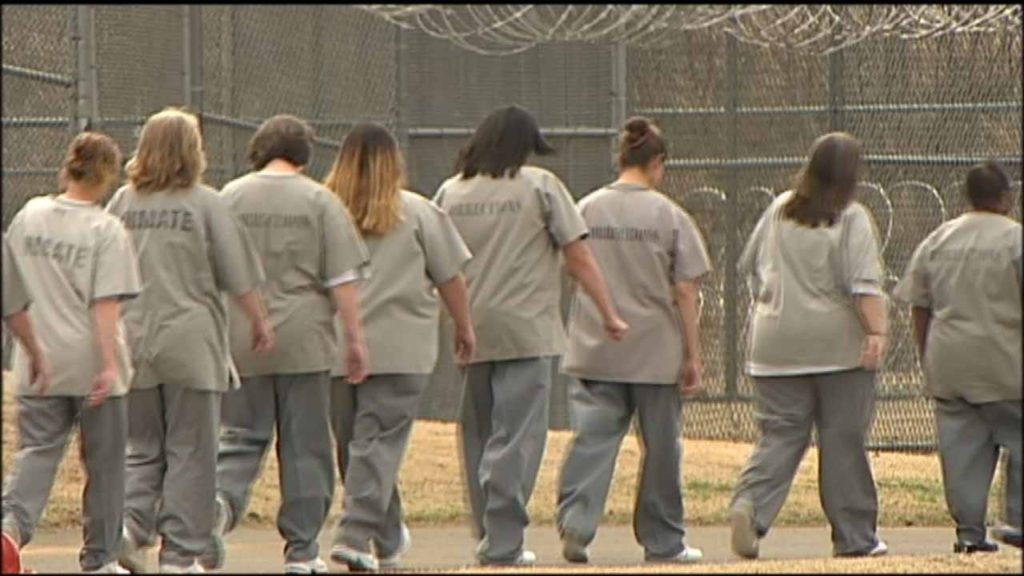

These policies have a face and body to them, and it’s Black, Brown, and female. The so-called War on Drugs has resulted in women being the fastest growing prison and jail population in the United States, and the vast majority of those women have been convicted of non-violent felonies that previously would not have resulted in prison or jail time or in disenfranchisement.

But it’s not all bad news.

This year, Alabama, California, Maryland, and Wyoming eased various restrictions. For example, Maryland restored voting rights to people on probation or parole. With that, they restored the voting rights to around 40,000 people.

In Virginia, Governor Terry McAuliffe restored voting and civil rights to 206,000 people who had been disenfranchised permanently. Republicans objected, sued in the Virginia Supreme Court, which overturned Governor McAuliffe’s restoration of voting rights for people who had completed their sentences. So, Terry McAuliffe pulled a gubernatorial all-nighter, and, in August 2016, individually restored the voting rights of 12,832 individuals.

Meanwhile, Maine and Vermont have no restrictions. None. In prison? Your vote counts. On parole or probation? Your vote counts. Served all your time, including prison and parole? Your vote counts. Your vote counts. Period.

A river of disenfranchisement runs through the electoral process, but people are refusing to drown in it. Across the country, organizations are pushing for an end to felony disenfranchisement and a recognition of the injustice that has been put upon communities of color, and in particular women of color. Whatever happens on Tuesday, over 6 million people deserved better. Democracy matters.

(Photo Credit 1: The Atlanta Black Star) (Video Credit: The Atlantic / YouTube) (Photo Credit 2: Louisiana Justice Institute)