I did not need to watch the Depp/Heard trial. The endless documentation around it and its live feed are meaningless. Even if the libel defendant were destroyed, aggressive, confused and/or totally without credibility, it would not change my opinion.

In my opinion, the person with gender privilege, more money, more symbolic power and more fame, not to mention more physical torque, is far more at liberty to walk away from a conflict than a person who has less of these things and is dealing with gendered ideology — a thing that lives in the minds of many femmes people, particularly cis-het women, reminding forever that femmes or childbearing bodies can be and are frequently trafficked, femmes minds are not valued; bank accounts not owned by men are precarious (as in evidence in the case of Britney Spears), and that displeased het-men have a social history of violence. Any invocation of the witch trials reminds that those bodies historically described as “women” are constructed as disposable.

Though in many contexts, these fears may be much less relevant, the true lovers of femmes people will understand that this internal siege exists and help us feel safe. Since the “Depp is innocent” campaign, that internal dreamscape has become a more, not less, dangerous place. Now that he has won his case, the dangers of that dreamscape will pierce the membrane into reality with the help of that repository called the internet.

The non-imperial gender and less powerful person in a relationship is far more likely to be stripped of other forms of material and social power if they are the one to choose to leave. Though I have little interest, fascination or even patience for a ‘Hollywood set’ of huge means, this relatively ‘less’ is of great importance when we are talking about ‘the union between a man and woman’ in the spectacle. Because it’s here in cis-hetero-ville that patriarchy finds itself and simmers its eggs against any social or structural change. When the imperially gendered famous person can pay an entire media machine to produce its slogans and re-frame events, his ex-wife has every reason to be and to have been terrified. Breakups for the person with less social power can be exponentially more frightening; they carry with them more potential for exile and violence. With the femmes gender having a history of being property, the gender who has been permitted to feel entitled to that property may construct being left as a form of being expropriated.

At the scale Heard will face here, where one can be certain that such an actress will face an entire regime of misogynistic death threats from other similarly entitled/sex privilege expropriated people, and with the more powerful actor most assuredly knowing that such harassment exists, it’s hard not to assume that his abuses continue.

Since I’m a reader, not a watcher, the bits I have caught pertain to some jocular death threats issued by Johnny Depp for whom the Stanford Experiments defense is suddenly deemed relevant. “Burn the witch” is not only misogynistic, it’s an elemental and originary form of misogyny. It represents a fundamentalist dogma of hate towards life-bearing bodies and a reference to a ‘first cause’ of a gendered regime change that brutalized bodies with vaginas. Team Depp argues that the context for him writing these texts was terrible, and so he became terrible. But why does this line of reasoning not work for Amber Heard? Was the context not also somehow terrible for her?

Indeed, what must a woman do to save her life? Sometimes the material manifestations of such decisions are surprising as, for instance, when Lucy DeCoutere gave Jian Ghomeshi flowers. That she did this was also used to prove Ghomeshi’s innocence in Canada. Fear does a lot of things to people: it can make them hyper-conciliatory, or it can make them enraged. But one thing is certain: the double standard has been holding in case after case.

It doesn’t matter to me that Winona Ryder (an actress I am a fan of as much as I can “like” any of these people) or Kate Moss didn’t experience violence with Depp. Sometimes a rapist abuser has a pattern that is obviously visible among his exes, and sometimes he doesn’t. While the pattern could serve as evidence, it’s not a foregone conclusion that if no one else comes forward, then he must be “innocent.” Perhaps Depp has categories of people he abuses, and categories he doesn’t. Perhaps he felt he could get away with exploring his violent side with Heard in particular; perhaps he was drunk. The reason doesn’t much matter. In any scenario, it still would have been much easier for him to walk away and shut the door than it would have been for her because the world doesn’t punish men, and particularly famous White, powerful men, the way it punishes every other identity at every social level.

Whatever Heard is or isn’t, she isn’t lying when she says that the judgment of this case hurts everyone. The judgement that proclaims Depp as “innocent” hurts abuse victims by making them more afraid to come forward, and it hurts abusers by declaring their innocence and thereby “finishing” the episode in what appears to be their favor. While it may look like a win, it actually deprives the abuser of self-reflection and the possibility of change and growth. More crucially, it deprives all of us because it re-installs the rigidity of gendered roles in marriage, men permitted to be controlling and women expected not to fight back and/or stay silent about what they endure; or that women’s roles remain circumscribed, though perhaps prescribed in kind by the whims of a particular era. Such a judgment reifies patriarchy at the center of the internet tabloid sphere, making a serious matter into a fluff piece about a woman’s derangement. So long as we live like this, there will be more Putins, Trumps, Enrons and all the forms of social destabilization created by excess greed, and a class of mostly White-man-people who are judged immune from ethics.

The raison d’etre of libel cases has often pertained to missed job opportunities. In this case, the consequence of Depp not issuing a libel accusation against Heard might have meant that he no longer would be allowed to make more pirate movies. But he would have assuredly not starved because of this, and indeed, it might be time for a new actor to benefit from such an opportunity. That blockbusters require a star in order to maintain their dominion over what adults and children watch is also problematic, normalizing, exclusionary and controlling.

If Depp were ethical, he would have written a well-considered op-ed back to Heard’s, supporting the social movements of femmes bodily autonomy namely the right to live without abuse and rape. He could have corrected where he thought she was wrong or talked about trying to understand how certain acts could, at least, have been read, understood or felt by her as they were in the context of his own predicament. He, like any other imperial identity in his position, could use such a moment to evolve the conversation, to avow his acts of cruelty or callousness, to read and learn about gender violence and support all of us in the travails and discomforts of what it means to truly and respectfully love the other and co-exist and co-create the world with them.

An onslaught of “Johnny Depp is innocent” is an abuse of the entire systemic socius for his petty battle. It ignores what the power of these signs do and which engines they feed. Maybe Depp did or did not abuse Amber Heard, but the accusation and judgment that supports libel abuses all of us. On that alone, Depp is an abuser.

(by Dora Bleu)

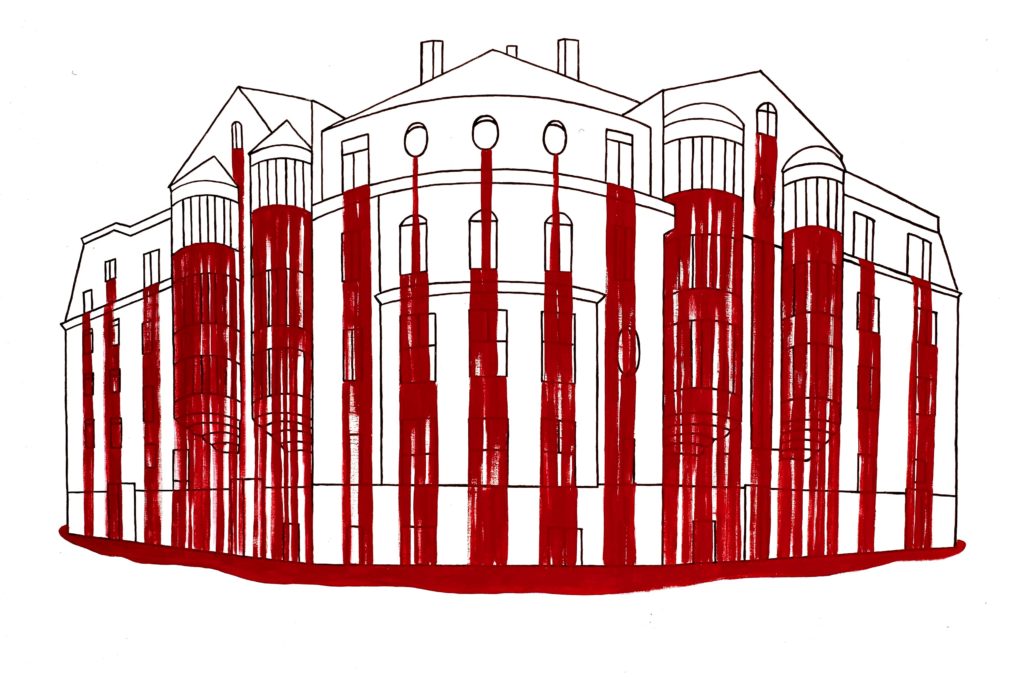

(Image credit 1: “Bleeding House Somewhere in Miami-5”, by Marko Mäetamm / The Cotton Factory)

(Image credit 2: “Bleeding House – 10”, by Marko Mäetamm / The Cotton Factory)