This week, two events returned to center stage the forced sterilization of largely poor women of disenfranchised ethnic minorities. In Peru, former President Alberto Fujimori and three of his Ministers of Health – Marino Costa Bauer, Eduardo Yong, and Alejandro Aguinaga – were told they are being investigated and will face charges for the forced sterilization of five women during his time in office. Also this week, in California, state legislators are debating a bill that would establish a “eugenics sterilization compensation program.” From Lima to Sacramento and beyond, once more, the monster women refuse to stay silently buried underground.

Alberto Fujimori was President of Peru from 1990 to 2000. In 1996 Fujimori modified the so-called General Population Law, incorporating “voluntary” sterilization an acceptable contraceptive method. In 1996, the Reproductive Health and Family Planning Programme was launched. From 1996 to 2000, over 300,000 women were sterilized. The overwhelming majority were poor and indigenous. The overwhelming majority never consented to the procedure. Many didn’t even know it was occurring. Over 2000 cases have been lodged against the sterilizations. As many as 18 women died because of the sterilization procedures. In 2014, Fujimori was cleared of any wrongdoing concerning forced sterilizations. In 2009, Fujimori was convicted to 25 years in prison for human rights abuses. Late last year, at the age of 79, Fujimori was released from prison, because of ill health. This week, he was informed that he would be facing charges concerning forced sterilization.

For fifteen years, Peruvian women have struggled and pushed for this moment. For example, year in and year out, the women’s rights organization DEMUS, Estudio para la Defensa de los Derechos de la Mujer, has documented cases of forced sterilization and called on the government to act. In response to the announcement of forthcoming charges, DEMUS issued a statement, calling the decision “a milestone in the struggle against impunity, one that highlights the national policy of forced sterilization against thousands of Quechua-speaking, peasant, indigenous and native women living in extreme poverty, which perpetrated grave violations of human rights. With their courage and persistence, the 2166 women who, 15 years ago, filed a complaint, today, with this case going into judicial investigation, finally take a step forward towards their right to justice.”

In California, the state legislature is considering a step forward as well. In 1909 California passed laws allowing for forced sterilization. California was one of 32 states that gave allowed for coerced sterilization of those `unfit’ to reproduce. In 1979, California officially banned forced sterilization, but in its prisons, forced sterilization, especially of women, continued until 2010. From 2006 to 2010, 144 women prisoners were sterilized “without proper authorization”. In 2014, California formally banned forced and coerced sterilization of women prisoners … again. By 1979, California forcibly sterilized over 20,000 people. The Latinx population was targeted. Prior to 1926, Latinos were targeted. From 1926 to 1979, Latinas bore the brunt of the eugenics sterilization program. Latina women and girls were at a 59% greater risk of sterilization than non-Latina women and girls. Needless and necessary to say, the Latina woman and girls were also overwhelmingly poor.

In early April, California State Senator Nancy Skinner introduced SB-1190 Eugenics Sterilization Compensation Program, which would offer compensation to living survivors of California’s sterilization decades. It is estimated that the Compensation Program would involve around 800 survivors, many of whom to this day do not know that they were sterilized. In establishing a compensation program, California would join Virginia and North Carolina.

Finally, “the bill would require the State Department of State Hospitals and the State Department of Developmental Services, in consultation with stakeholders, to establish markers or plaques at designated sites that acknowledge the compulsory sterilization of thousands of people. The bill would also require the board, in consultation with stakeholders, to develop a traveling historical exhibit and other educational opportunities about eugenics laws that existed in the State of California between 1909 and 1979 and the far-reaching impact they had on California residents.”

In both Peru and California, reports of judicial investigation in one and legislative action in the other are woven through mountains of haunting, heartrending accounts of survivors, family members, friends. For decades, these stories have been shrouded and buried in layers of State and public silence. Thanks to women who refused to be stopped, who struggled with courage and persistence, the days of enforced silence about forced sterilization are nearing an end. The time for acknowledgement, reparations, and education is now.

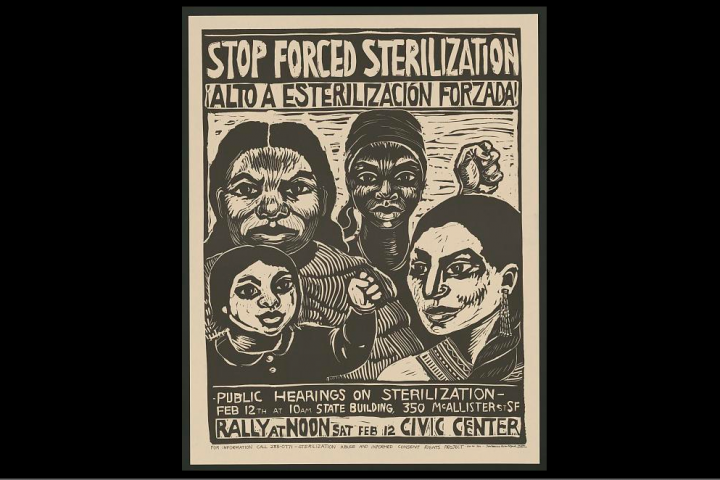

(Photo Credit: El Pais / Reuters) (Image Credit: Journalists Resource / Rachael Romero)

(Video Credit:

(Video Credit: