R. Pranathi’s relatives argue with police

Mwanahamisi Mruke and R Pranathi are two faces, two names, for global domestic labor. Perhaps they are the same face, the same name.

R Pranathi is a domestic worker in Ennore, a suburb of Chennai, India. For the last four months, she has worked as a household worker in a constable’s family. She comes from a poor family. She has worked in the house and taken care of the couple’s child. Pranathi is known as “a brave girl who would fight eve teasers in the locality.”

Pranathi is 14 years old, and she is dead.

The couple’s story is that the girl suffered stomach pains and hanged herself. People from her hometown and members of the Tamil Nadu Domestic Workers’ Union have a different story: the girl was raped, murdered, and then `translated’ into a suicide.

Whether or not Pranathi’s death was murder, and one suspects it was, the story of domestic workers being killed and then translated into suicides occurs every day, all over the world. Some gain some notice, such as the 31-year-old Nepalese domestic worker Samoay Wanching Tamang, who died by hanging in Lebanon in late February. Others simply vanish into the void. Some deaths are said to be mysterious, others are allegedly clear-cut. What is not mysterious is that domestic workers are dying, at work, across the globe, at an alarming rate.

Domestic labor is a growth industry, but it is also a labor killing field. And the ways of dying are many, some swift, others slow.

Mwanahamisi Mruke suffered the slow death. In October 2006, Mruke left Tanzania for England, where she had been promised employment as a domestic worker. She left her home and homeland for higher wages that would allow her daughter Zakia to attend college. She went to work for Saeeda Khan, a widow with two adult disabled living children, a hospital director with a good job. Khan kept Mruke a slave for the past four and a half years. Mruke’s passport was taken away, she was not allowed to leave the house, she worked from six am to midnight, sometimes more. Mruke was forced to sleep on the kitchen floor. After the first year, Khan stopped paying the worker. She was “treated like a slave.” Slavery, as sociologist Orlando Patterson explained in his magisterial work, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study, “the slave’s powerlessness was that it always originated (or was conceived of having originated) as a substitute for death, usually violent death.”

On Wednesday, March 16, 2011, in a groundbreaking case, Saeeda Khank was found guilty of trafficking a person into the United Kingdom for exploitation. Mwanahamisi Mruke is now pursuing a civil suit.

These stories are an intrinsic part of the fabric of global waged domestic labor, one of the major growth industries of the past three decades worldwide. On one hand, they tell the story of terrible employers. Venal, corrupt, violent and vicious. It’s an important story to tell.

But there’s another story as well, that of the isolation, the silence, the exclusion of domestic workers from the world of workers and of labor.

This year, on May 1, 2011, Hong Kong will implement a Minimum Wage Ordinance. The new legislation will apply to full-time and part-time employees, regardless of whether they are employed under continuous employment contracts. Anyone who has been employed continuously by the same employer for four weeks or more, with at least 18 hours worked in each week, will be covered.

Almost anyone, that is: “the MWO does not apply to certain classes of employees, including live-in domestic workers, certain student interns and work experience students.”

In British Columbia, in Canada, this week, the minimum wage has been increased for the first time in ten years. This is good news, but does it cover domestic workers? Jamaica awaits a government study on livable wages. Will the study consider domestic workers?

In June 2011, the International Labour Organization may adopt a Convention on the rights of domestic workers. If so, it would aim to strengthen legal protection for the billions of paid domestic workers around the globe. The ILO Convention could be an important step. But it depends on the language of respective member countries’ labor laws.

Until the trade union movements formally include domestic workers in every worker protection campaign, in every campaign and action, billions of paid domestic laborers will remain super-exploited and under a death sentence. Employers have indeed been known to isolate, imprison, torture, and even kill domestic workers. But the rest of us, in our day-to-day failures and refusals to see domestic workers as real workers, and domestic labor as real labor, exclude, silence, and isolate precisely those workers. Mwanahamisi Mruke and R Pranathi haunt us.

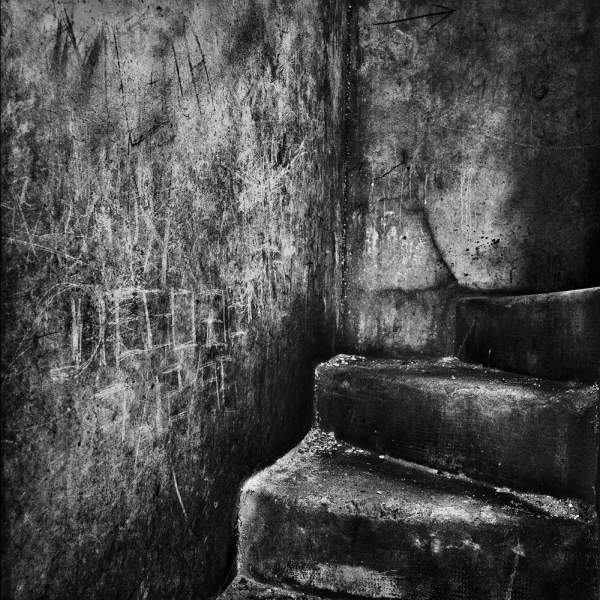

(Photo Credit: The New Indian Express)