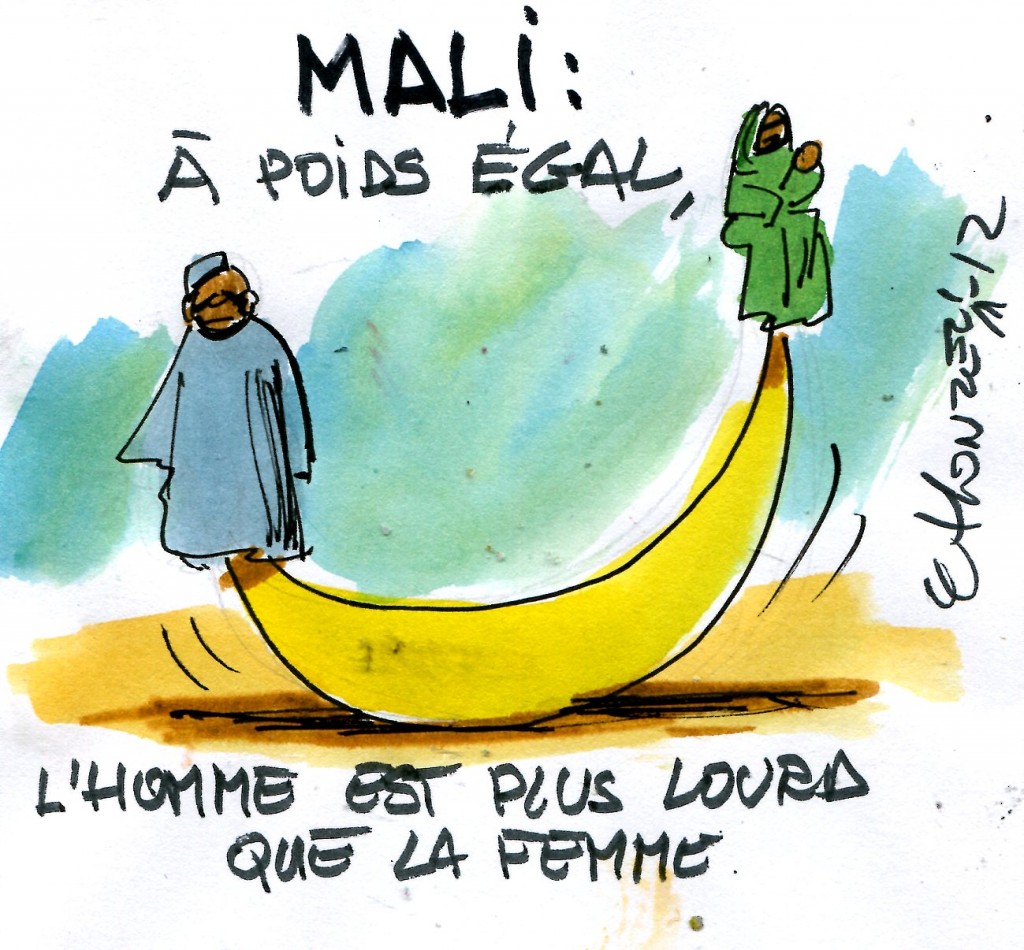

On December 2, 2011, the Malian parliament passed a Family Code, which threatens to set back women’s rights in Mali quite considerably. In 2009 the Parliament had passed a fairly progressive law, which didn’t quite bring women and men to equal status, but was a major step in that direction. Conservative, mostly religious, forces swung into action. The President quickly rejected the law, and sent it back to Parliament, where it has sat for two years. The new bill declares women’s legal obligation to obey and serve their husbands, as well as the husbands’ singular leadership, or dominion, over the household and all within it. Many argue that such terms violate the national Constitution, specifically in the articles where it codifies the meaning of Malian nationhood as an independent, democratic, sovereign, secular republic.

Women of Mali were immediately, and continue to be, indignant. More than indignant, they are indignées. They are organizing the Malian Spring.

The `world’ knows and often recognizes the labor and leadership of Malian women. Women like singer-songwriter Fatoumata Diawara, currently setting the world ablaze, and the even-better known singer Mariam Doumbia, who with her partner Amadou Bagayoko, continue to welcome the world to Mali and to set the dance floors on fire.

Militant and feminist women singers like Oumou Sangaré join younger defiant women singers such as Khaira Arby. Fiercely feminist women writers such as Oumou Ahmar Cissé have been writing, and organizing, for the rights and autonomous spaces of women and girls, while visual artists, like photographer Fatoumata Diabaté, continue to document and interpret the worlds of social relations, and in so doing awaken the art world to a new kid on the block.

Meanwhile, women like Fatoumata Dembel Diarra, First Vice-President of the International Criminal Court; and Cissé Mariam Kaidama Sidibé, current Prime Minister of Mali and the first woman PM of the country, have kept on keeping on, breaking new ground, shattering old glass ceilings.

This a short list, an incomplete list, of Malian women who have been identified, in the last year, as `women to watch’, women to follow. And they are on the move.

Some twenty organizations started a petition, NON AU NOUVEAU CODE DES PERSONNES ET DE LA FAMILLE DU MALI ADOPTÉ LE 2 DÉCEMBRE 2011! It begins: “Indignons-nous face au nouveau Code des personnes et de la famille, qui vient d’être adopté en seconde lecture par l’Assemblée Nationale, le 2 décembre 2011.” That opening has two senses. First, we are indignant, or outraged, at the new Code. Second, and more to the point, we are the indignants, les indignées, and we are fomenting indignation.

Women’s organizations like WILDAF Mali, Women in Law and Development in Africa, have been pulling women, and men, together into various formations to inform and to organize. On December 31, they pulled together representatives from over twenty organizations to think through the intricacies of the new bill and of the new moment, to strategize and to begin to implement counter-strategies. And they are on the move.

This is what Malian women do. They organize. They don’t wait. Some have suggested, “For more than 10 years, women in Mali have been waiting for the adoption of a Family law to protect their fundamental rights.”

The women of Mali have not been waiting. They have been organizing, and now … they are les indignées du Mali, and their battle cry is direct: “Indignons-nous!” That phrase means Spring is coming to Mali. Indignons-nous!

(Photo Credit: Contrepoints)