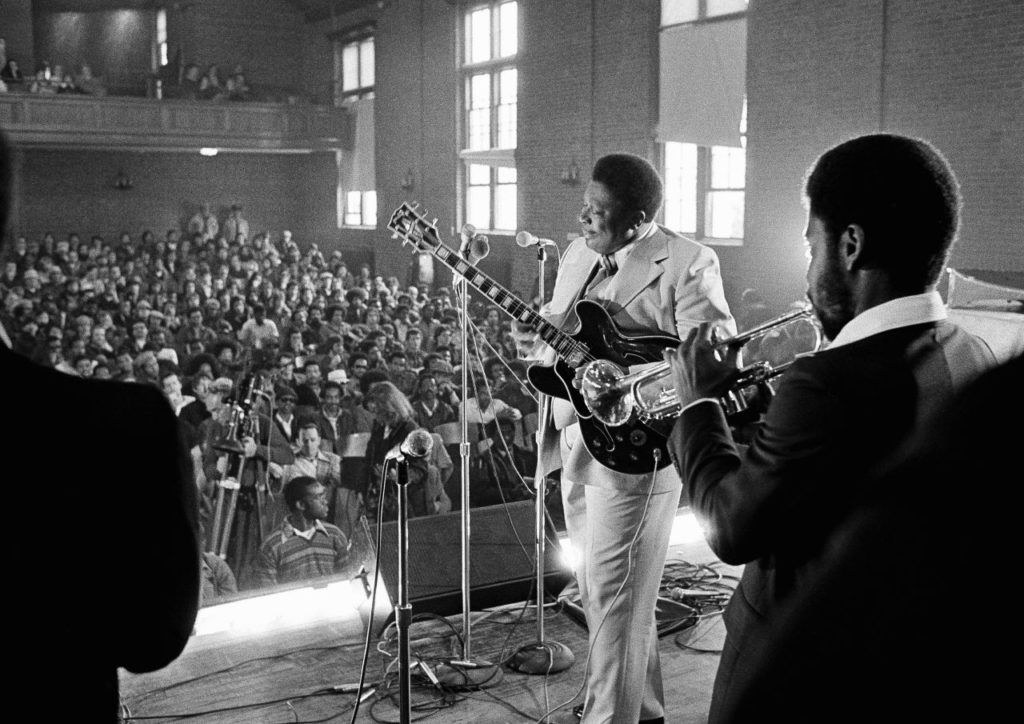

B.B. King played to a packed auditorium at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution in Norfolk, Mass. on April 3, 1978.

BB King is no more

we get to hear late

on Al-Jazeera News

(I take out my Royal Jam

The Crusaders playing

with BB King and the

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

on LP record of course)

The Thrill is Gone

a favourite of old

of mine and a grey-headed

neighbour down the road

The Thrill is Gone

Eric Clapton and Ringo Starr

and imperialism’s head-honcho

are duly and dutifully quoted

(what an improbable trio)

The Thrill is Gone

electric blues guitarist

who influenced many

(even did the prison circuit)

(he taught himself the guitar

he too was influenced

by those before even

by an aunt who had

blues and jazz records)

The Thrill is Gone

son of tenant farmers

yonder Mississippi Delta

the home of the blues

The Thrill that is BB King

is gone though

the blues is all around

Last month,

Last month,