According to today’s Express Tribune, in Sindh, one of Pakistan’s four provinces, jails are “bursting at the seams with twice the population”. Some jails are at six times their prescribed capacity. In another piece, still in today’s Express Tribune, in Punjab, the most populous province in Pakistan, 927 women are currently incarcerated. Of those women, 91 are mothers currently living, in prison, with their children. What do these numbers mean, and, even more, where are the women?

Sindh’s three women’s jails are located in Karachi, Hyderabad, and Sukkur. Together, they house 486 women. Their official capacity is 420, and so they’re 18% over capacity. To put that in perspective, Sindh’s jails’ official capacity is 13,500, and they currently house 23,500. The jails for men and women are 74% over capacity. Here’s the thing about the incarcerated women’s `rosy’ picture. Of the 486 incarcerated women, 421 are under trial, or remand, prisoners. That is, they are awaiting trial. 87% of the women have not been convicted of any crime. For the general prison population in Sindh, 77% are awaiting trial. If the State were to release people, and especially women, before trial, not only would there be no `prison overcrowding’ … there would be almost no prison. Further, if the State were to release women who are awaiting trial, the impact on their children would be beneficial.

Which brings us to Punjab, where 927 women are incarcerated. 91 of them are mothers raising their children in prison. Of the 91 mothers, 67 are awaiting trial. 74% of the women are officially not guilty of anything, but they and their children must suffer incarceration. As is so often the case around the world, the women explain they are charged with having assaulted abusive partners. In other cases, the partners can’t take the children, for any of a number of reasons, including divorce. And so, in one province alone, 105 children under the age of six live and grow, or not, in prisons, where the schools are mostly missing in action and where the environment is cruel and inappropriate.

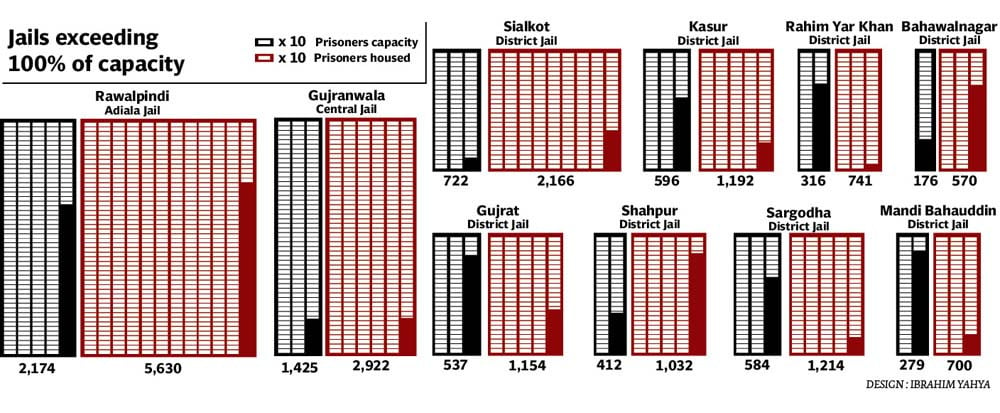

Meanwhile, Punjab jails are 38% beyond their prescribed capacity. The jails experience regular food shortages, as well as staffing shortages. Punjab has 42 prisons; 21 have no doctors. The whole system has a grand total of 40 doctors, for a population of close to 51,000 and growing … and getting sick and dying.

At the end of last year, Pakistan’s prison and jails housed 85,670 individuals, of whom 60,000 – 70% — were awaiting trial. At that time, 1399 women were incarcerated. It’s not clear how long people wait in overcrowded, toxic, life-threatening conditions for `justice to be served’, but it is clear that the situation is untenable. None of this is new: “Pakistan inherited an outdated prison system from the British colonial regime in India and it has not changed much in over 200 years. Even today, the Prisons Act 1894 and the Prisoners Act 1900 are the main laws which govern prisons and prisoners in Pakistan.” The Prisons Act 1894 emerged from recommendations of the 1838 Prison Discipline Committee.

From 1838 to 2022, and beyond, from Pakistan, and India, to England and beyond, women and children suffer indignity, violence, cruelty, disease and death because State policy has created the circumstances in which prisons are crowded `beyond capacity’. You know what is within our capacity? Justice. Shut the prisons and jails. Decolonize justice systems today.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Infographic credit: The Express Tribune)

Last month,

Last month,