Today, Scotland’s Mental Welfare Commission released the findings of their investigation into the treatment of women with complex mental health needs who have the great misfortune of ending up in Scotland’s one all-women’s prison. The Commission reports that women with mental health needs were sent into solitary confinement, euphemistically called Separation and Reintegration Units, for anywhere from a day to 82 days. The cells are described as “sparse and lacking in comfort. The narratives in women’s notes suggested there was little in the way of positive sensory stimulation in the environment of the SRU. There was limited human contact and if other women in the SRU were distressed or unwell, their vocalisations were likely to be audible, disturbing and distressing. When women’s self-care deteriorated, they may also have experienced physical and sensory discomfort in this context.”

The report goes on to note, “Part of the ethos, and indeed the name of SRUs, is that offenders are reintegrated into the mainstream environment after a period of time. Reintegration did not appear to feature in the majority of cases we reviewed …. For women who were floridly unwell with acute psychosis or manic psychosis, the severity of their symptoms and level of disturbance significantly worsened in the SRU.”

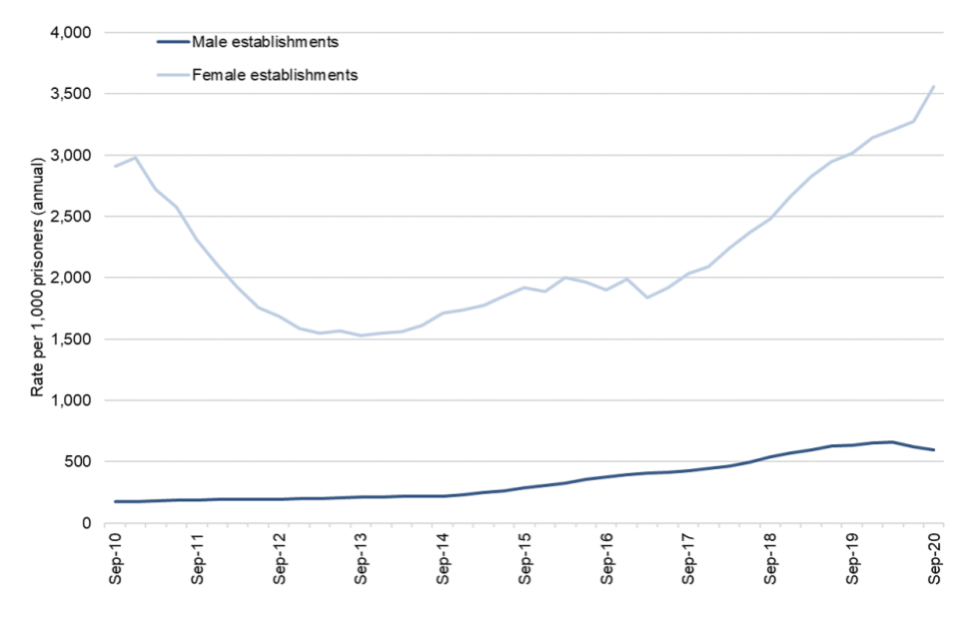

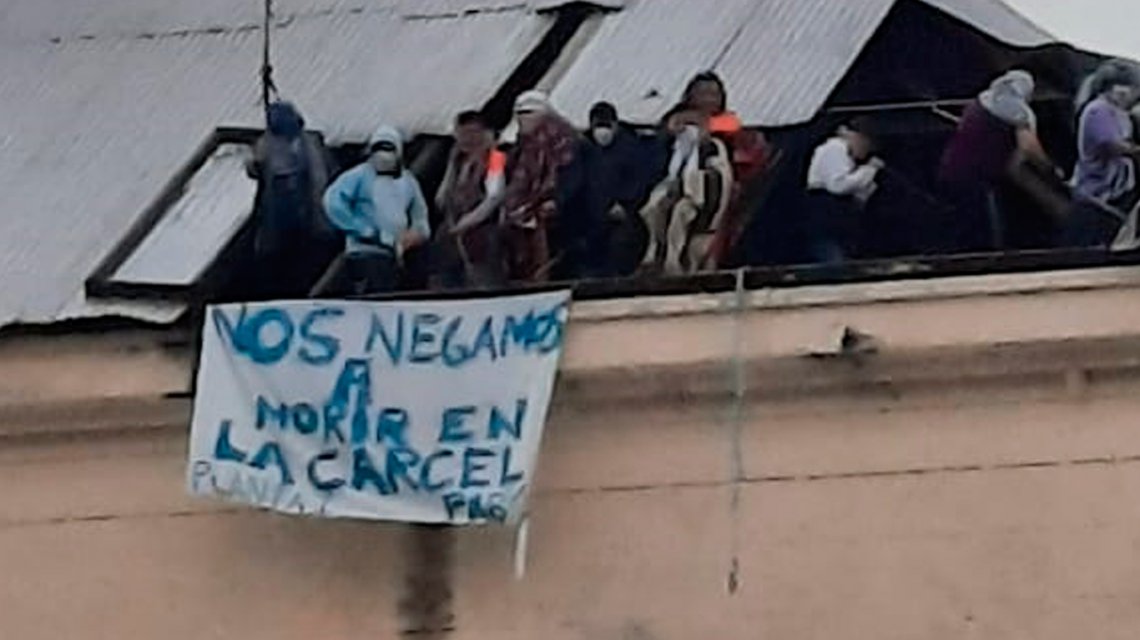

None of this is surprising or new. That solitary confinement, for anyone, is torture is not new. That solitary confinement as a response to women’s health needs is torture is not new. That solitary confinement as a response to women in need is, nevertheless, altogether ordinary also is not new. That solitary confinement worsens everything is also not new. That Cornton Vale is a toxic hot mess, with high levels of suicide and self-harm is also not new. Due to its high rates of suicide and self-harm, Cornton Vale has been called the “vale of death”. None of this is new or surprising.

In 2018, the European Commission on the Prevention of Torture visited Cornton Vale: “The CPT raises serious concerns about the treatment of women prisoners held in segregation at Cornton Vale Prison …. The CPT found women who clearly were in need of urgent care and treatment in a psychiatric facility, and should not have been in a prison environment, let alone segregated for extended periods in solitary confinement under Rules 95 and 41 (accommodation in specified conditions for health or welfare reasons). Prison staff were not trained to manage the highly disturbed women.” When they returned, in 2019, they found that the situation was somewhat improved, in some senses, but that the use of segregation, and in particular long-term isolation, persisted. None of this is new or surprising.

What is new is that this is not new. On July 10, 2017, Nicola Ferguson Sturgeon, First Minister of Scotland and leader of the Scottish National Party, wrote, “Tomorrow sees a major milestone in the transformation of our justice system. We will begin the demolition of Cornton Vale women’s prison, a move that marks the next stage in our plans to ensure Scotland’s penal policy doesn’t just punish people who’ve committed crimes – important though that is – but helps deliver safer communities in the long term.” What happened? Why, four years later, is Cornton Vale still standing? What happened to the alternatives — an 80-bed prison, five regional 20-bed facilities, community sentencing and service, and much greater funding for mental health, drug abuse, counseling? What is the investment in Cornton Vale’s catastrophic failure, such that, four years later, the vale of death, the vale of women’s slow and painful death and deaths? Haven’t there been enough inquiries and enough `discoveries’, enough corpses and enough ruined lives?

(By Dan Moshenberg)