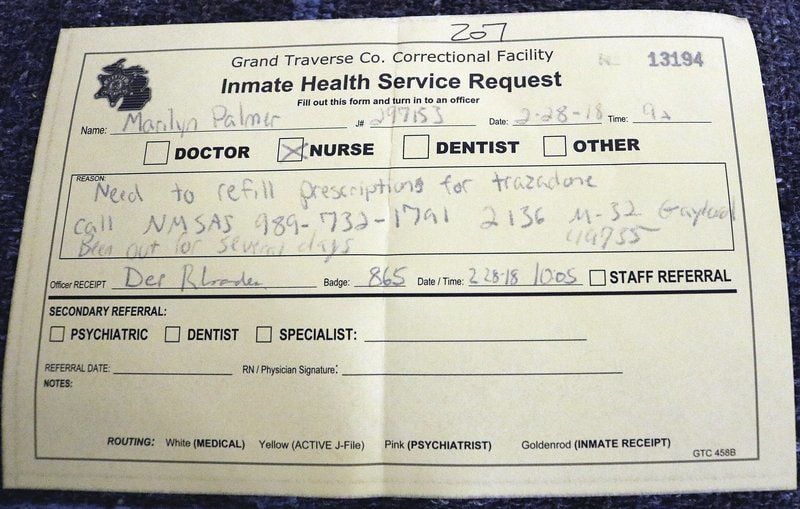

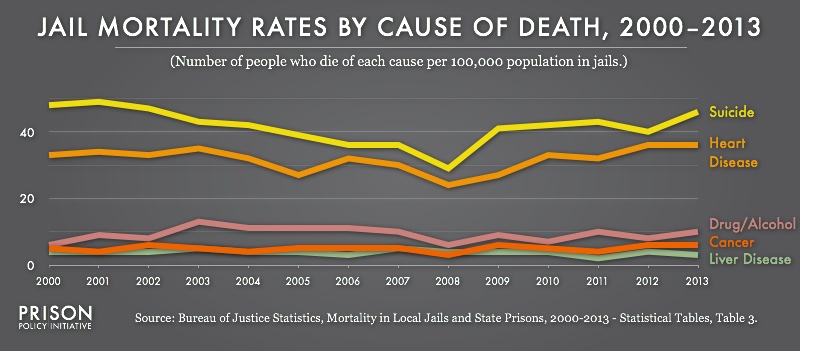

The Federal Bureau of Justice Statistics released its report on suicide in local jails and state and Federal prisons from 2000–2019. None of it is good or surprising. Since its last report, the number of deaths by suicide among women in local jails in the United States increased by almost 65%: “The number of deaths by suicide among female local jail inmates increased from 124 to 204 deaths between the periods of 2000-04 and 2015-19, rising almost 65%.” What else is there to say? If the numbers and rates of suicide rise year by year, that means the system thinks this rising is a mark of success. And who are those women. 77% of those who committed suicide in local jails were awaiting trial. The report refers to these people as “unconvicted inmates”. Unconvicted. Unconvicted, a word that is not a word and expresses everything. Here are a few of those unconvicted women: in Texas, Sandra Bland, 28 years old, Tracy Whited, 42 years old; in Alabama, Kindra Chapman, 18 years old; in Massachusetts, Jessica DiCesare, 35 years old; in California, Wakiesha Wilson, 36 years old; in Washington State, Tirhas Tesfatsion, 47 years old; in Indiana, Ariona Paige Darling, 18 years old. They are survived by children, partners, parents. Like so many others, they were all unconvicted. Innocent until proven …

Unconvicted.

Yet again, another report discovers what we already knew, yet again we encounter the ordinary, everyday reality of necropower: “Contemporary forms of subjugation of life to the power of death (necropolitics) profoundly reconfigure the relations among resistance, sacrifice, and terror …. In our contemporary world, weapons are deployed in the interest of maximum destruction of persons and the creation of death-worlds, new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead … Under conditions of necropower, the lines between resistance and suicide, sacrifice and redemption, martyrdom and freedom are blurred.”

When the State can report, as just another data point, “unconvicted inmates accounted for almost 77% of those who died by suicide in local jails during 2000-19”, we have moved beyond necropower. We are in the country of the unconvicted women condemned to die by suicide where justice is a line between who must be executed and who must commit suicide.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Infographic Credit: Prison Policy Initiative) (Image Credit: Tate Modern)