In 1995, Canada opened the Nova Institution for Women, in Truro, Nova Scotia, and it’s been a hellhole for women ever since. In 2015, Veronica Park died of pneumonia, after begging for days for health care, to no avail. Three months later, Camille Strickland-Murphy, after a series of incidents of self-harm and suicide attempts, none of which were attended to, killed herself. Earlier, in 2006, Nova Institution was the first station in Ashley Smith’s journey into suicide. In 2019, Samantha Wallace-Parker died of pneumonia, after begging for days for health care, to no avail. In 2020, Lisa Adamsexperienced Nova’s dry cell, a cell without running water or toilet, for 16 days. These are just the best known stories, all of which end up in court. But that was all `prepandemic’. 2022 opens with COVID running rampant through the Nova Institution for Women, and the thing is, all of this was predictable, everyone in charge knew, and they did nothing, worse than and less than nothing.

Today, Martha Paynter, who is “a registered nurse who researches prisoner health, and as a community advocate for people in prisons for women”, wrote, “The news that 49 people (24 prisoners, at least 25 staff) have now tested positive for COVID-19 at the Nova Institution for Women, a federal prison in Truro, brings a nightmare we foresaw … into reality … Federal prison is a $2.4 billion/year operation. We need to stop throwing money at this system and redirect it to meaningfully address the trauma and poverty that drives criminalization. The horror of mass infection at the Truro prison must finally change our thinking.”

Again, all of this was foreseen. In 2020, Martha Paynter wrote, “Prisons are petri dishes. Hundreds of people are under one roof with poor ventilation, barriers to health services, substandard nutrition, limited participation in exercise and time outdoors and inadequate information provision.”

What else is there to say? The petri dish has done what it’s designed to do. Advocates, like Martha Paynter, are calling on the State to release the women. The State has responded with lockdown. In one day, the cases jumped from 8 to 38. There’s less testing in federal prisons than in the general population, to no one’s surprise. In 2020, a study found the following: “There were 59 cases of COVID-19 in women’s penitentiaries. These represented 31% of all cases in federal penitentiaries, suggesting that women, and women’s penitentiaries, are over-represented among COVID-19 cases inside federal prisons. COVID-19 prevalence was 8 times higher among women’s prisons (8% prevalence) than prisons for men (1% prevalence) and 80 times higher than in the general Canadian population (0.1%).”

COVID-19 prevalence was 8 times higher among women’s prisons than prisons for men and 80 times higher than in the general Canadian population. That was two years ago. Today, the situation for women held in prison is worse. This is not failure, this is petri dish public policy, designed for incarcerated women. Don’t fix it, shut it down.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

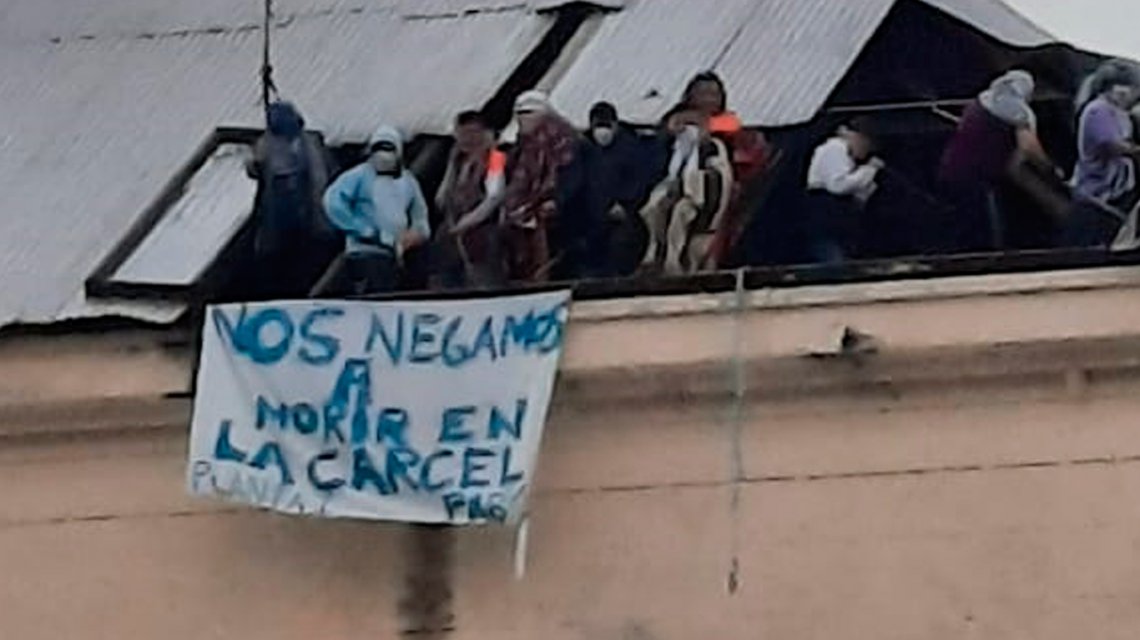

(Photo Credit: Saltwire / Chelsea Gould)

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2020/10/01/this-treatment-is-not-unique-to-joyce-indigenous-medical-workers-say-joyce-echaquans-death-is-the-latest-tragic-symptom-of-a-longstanding-health-care-crisis/justice_for_joyce_vigil.jpg)