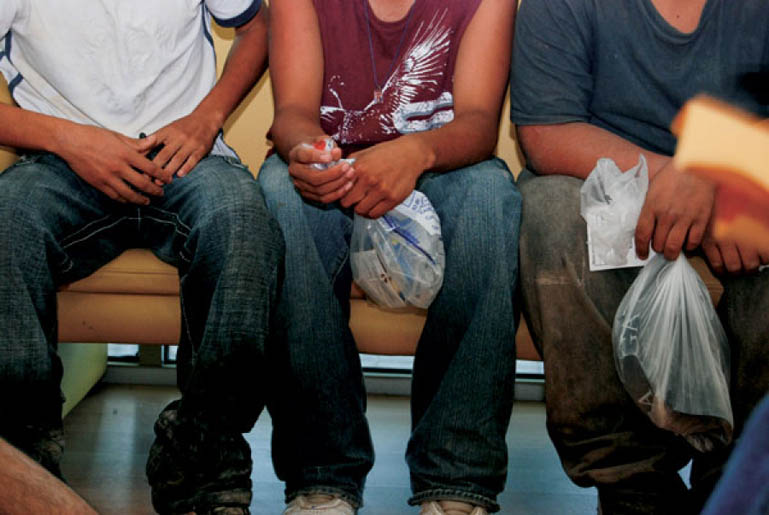

Children are disappearing. Sometimes spectacularly. Sometimes silently. Sometimes `without notice’. That children are disappearing is not new. Children asylum seekers and children of asylum seekers have been disappearing into detention centers in Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Greece, and elsewhere. In Australia, imprisoned children of asylum seekers are disappearing into the tortured self mutilation that must serve as a kind of escape from their current everyday circumstances. Children of incarcerated mothers are disappearing in South Africa, Scotland, the United States and elsewhere. Children in schools are disappearing into seclusion rooms, aka solitary confinement. In the United States, children of undocumented residents are disappearing, shipped like so much baggage, back to Mexico and parts unknown, often on their own. In Jamaica, girl prisoners disappear into prison fires that were altogether predictable and preventable. None of this is new. We have discussed this and more before. The events are not new nor is the failure to take responsibility.

Children are disappearing. Sometimes spectacularly, sometimes silently, other times `without notice’.

In England, an inquest opens today. It’s the second time around for this inquest. It concerns the death in custody, in August 2004, of Adam Rickwood. Adam was 14 when he was found hanging in his cell at Hassockfield Secure Training Centre, a private prison run by Serco, the same people who run Yarl’s Wood in the UK and all the immigrant detention centers in Australia, most notoriously Villawood.

When Adam Rickwood, who had never been in custody before, refused to go to his cell, he was `forcibly restrained’ with `a nose distraction’, a violent and invasive chop to the nose. Hours later, he was found dead, hanging, in his cell. At the first inquest, in 2007, the coroner refused to let the jury decide if the restraint constituted an assault. It took thirteen years of struggle on the part of Adam’s mother, Carol Pounder, before the first hearing took place. Dissatisfied with the complete opacity of the system, she continued to push, and finally, finally a second inquest has been ordered. That starts today. Adam Rickwood would be thirty years old now.

Meanwhile, across England, there are 6000 children whose mothers are incarcerated, and, basically, no one officially knows their whereabouts. According to the Prison Advice and Care Trust, or PACT, they are “the forgotten children.” According to PACT, the mothers of 17,000 children are in prison, and of those, 6000 are not in care nor are they staying with their fathers. They are `forgotten.’ Children are disappearing, some into the night, others into the fog.

At the same time, in Ireland, eleven unaccompanied children asylum seekers went missing last year. Six have yet to be found. Between 2000 and 2010, 512 unaccompanied children seeking asylum were `forgotten’. Of those, only 72 were ever found by the State. Forgetting children is not an exception, it’s the rule, when the children are children of color, children of asylum seekers, children of the poor, children in prison. Children of strangers, children of neighbors are disappearing, into the night, into the fog.

In the United States, Phylicia Simone Barnes is a 16 year old honor student from Monroe, North Carolina. In December, she was visiting Baltimore, thinking of attending Towson University, a local university. Phylicia went missing on December 28. There has been little, very little, media attention, despite the efforts of family, the Baltimore Police Department, and the FBI to draw attention to this case. Why? Baltimore Police spokesman Anthony Guglielmi thinks he knows the reason: “”I can’t see how this case is any different from Natalee Holloway. Is it because she’s African-American? Why?” When teenager Natalee Holloway disappeared, on holiday in Aruba, there was a `media frenzy.’ For Phylicia Simone Barnes, who is Black, there is fog. She is a forgotten child.

Christina Green was born on September 11, 2001, to Roxanna and John Green, in West Grove, Pennsylvania. She was one of the 50 Faces of Hope, faces of children born on that fateful day. Like Phylicia Simone Barnes, Christina was a star student, an engaging child, bright, mature, `amazing’. She was killed on Saturday, in a volley of gunfire apparently directed primarily against Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords.

What becomes of hope when a Face of Hope is lost? Children are disappearing, sometimes spectacularly, amidst blazing gunfire, sometimes through a policy of practiced omission and amnesia. In the moment, the route of spectacle or silent lack of notice seems to matter. But in the end, they are all forgotten children, and they haunt the days and ways of our world.

(Photo Credit: BBC.co.uk)