The Sulphurous Hail

Shot after us in storm, oreblown hath laid

The fiery Surge, that from the Precipice

Of Heav’n receiv’d us falling, and the Thunder,

Wing’d with red Lightning and impetuous rage,

Perhaps hath spent his shafts, and ceases now

To bellow through the vast and boundless Deep.

John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book One

The print edition of today’s Washington Post leads off with a five-column, almost banner, headline, in large bold letters: “At the border a reset but no surge”. In the United States this week, with the declared end of the Covid emergency came the end of Title 42, a Trump era cruelty which barred entry into the United States on the grounds of maintaining health protocols (where have we heard that before?). That meant that starting yesterday, the country could anticipate a `surge of migrants crossing the border’. This was not the language of rabid far right nationalists. This was the language of the mainstream press, and so, perhaps, worth noting. CNN, May 10: “Hundreds of US troops are set to begin a new mission along the southern border Wednesday as officials and a surge of migrants brace “for the unknown” after a Trump-era border restriction expires late Thursday.” PBS New Hour, May 11: “The city of San Jose is preparing to welcome a significant influx of immigrant families in the coming weeks as Title 42 expires, creating a surge in immigration along the United States’ southern border.” New York Times, May 11: “In San Diego, some had been waiting in the same spot for days. State officials are concerned that a major surge in migrants could overwhelm homeless shelters and hospitals not just in the city, but across California.” Yesterday, May 12, The New York Times tried to explain that “surge” is a term of art: “On some days this past week, more than 11,000 people were apprehended after crossing the southern border illegally, according to internal agency data obtained by The New York Times, putting holding facilities run by the Border Patrol over capacity. Over the past two years, about 7,000 people were apprehended on a typical day; officials consider 8,000 apprehensions or more a surge.”

Words have meanings, and some words have ideological power. Often – as in the case of stampede or bruntor surge – the power of the word outweighs and obscures the word’s supposed meaning or content. What do you see, what do you feel, at the invocation of a surge? A surge is a force of nature: “A high rolling swell of water, esp. on the sea; a large, heavy, or violent wave; a billow.” Large. Heavy. And most significantly and ominously, violent.

People do not constitute a surge. People never constitute a surge. There never was going to be surge at the border, unless the Rio Grande suddenly exploded. There could have been and there still might be an increase in the number of people, fellow human beings, applying for asylum. That is not a surge. That the government, irrespective of which regime we are in, considers one number a trickle and one number a surge and, who knows, another number a tsunami is not so much irrelevant as dangerous and should be called out and rejected. The news media should be called out as well for passing the term off as somehow neutral. It is not.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

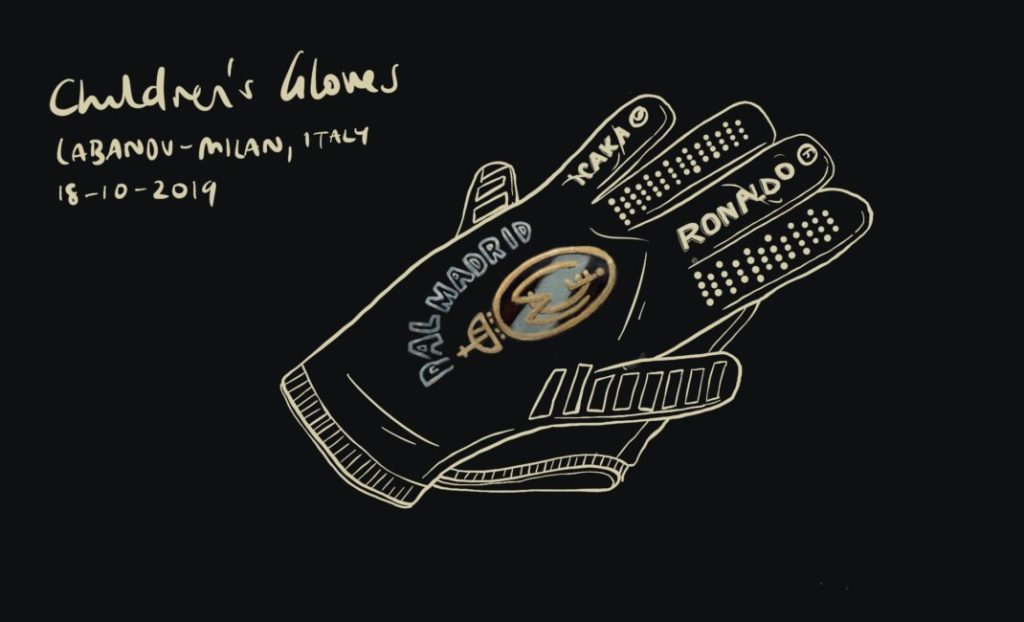

(Image Credit: “Surge” by Rachel Leising So0)