The Bentiu camp in South Sudan where Megan Nobert worked

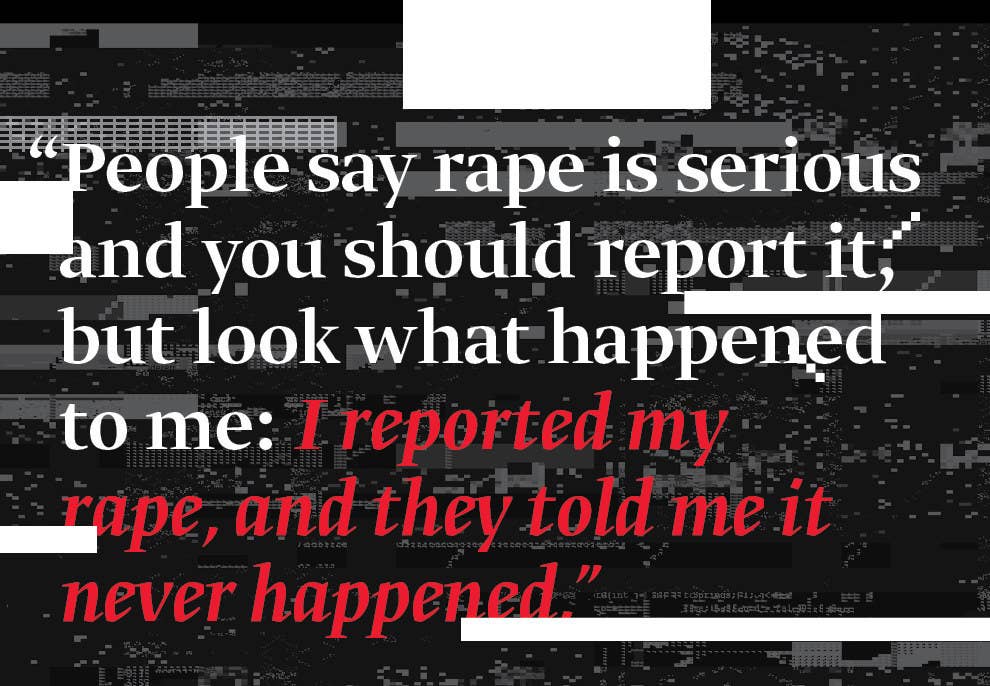

Sarah Pierce was an aid worker working in South Sudan for the Carter Center when she was raped by a co-worker. Megan Nobert was also in South Sudan, working as a humanitarian aid worker, when she was drugged and raped by another aid worker. The world of sexual violence is so distorted and distorting that Nobert’s initial account, in The Guardian, bears the headline, “Aid worker: I was drugged and raped by another humanitarian in South Sudan.” In what world do the words “humanitarian” and “rape” inhabit the same sentence? In our world.

Both Sarah Pierce and Megan Nobert have argued, to paraphrase Lara McLeod, “My rape was awful. But the way the police handled it was even worse.” In these two cases, and so many others involving sexual violence within the humanitarian aid community, the police never handled it. The Carter Center did less than nothing to help Sarah Pierce, other than ultimately firing her for her outspoken criticism of the organisation’s failure to help her. The United Nations never really investigated or did anything. Both organizations claim the incidents were tragic and the organizations did the best they could.

Up to now, there is practically no real research on sexual violence within the humanitarian aid community, despite the “issue” simmering just under the surface for decades. Only now has one organization, the Headington Institute, which provides psychological support for aid workers, begun a research project that hopes to assess the scale of the problem: “This is massively underreported: no one has an accurate read on this at the moment. Most agencies are hearing about these events internally, but survivors are choosing not to report for a variety of reasons. We think it’s likely that 1% or more (between 5,000-10,000 people) experience this during their humanitarian career. But male or female, this is an issue everyone fears, even if they are not naming it. It’s a worst-case scenario that everyone is thinking about.”

Megan Norbert joined forces with the International Women’s Rights Project and launched a campaign called Report the Abuse: Breaking the Silence on Sexual Violence Within the Humanitarian Community. They’ve gathered testimonies and are conducting a survey and are organizing for real change and real accountability. As Megan Norbert explains, “Today I want to talk to you about bravery, and that fact that it is considered to be brave to talk about being victimised by a crime like sexual violence. I don’t consider myself to be brave. In fact, I abhor the word, at least as it applies to myself and what I have done so far. Admitting to being the victim of a crime is not brave. Or, rather, it should not be. It should not be extraordinary to be able to say out loud, write or express in some way the following words: `I am a rape survivor.’ It should not be amazing that someone is able to discuss having been a victim of a violent crime because that is all that sexual violence, rape, is; it is a violent crime … Change will occur, work environments will adapt, perpetrators will be punished. We will no longer need to be afraid. It will no longer be considered brave for a humanitarian to stand up and say they were sexually harassed, abused or assaulted in the course of their work. This is my story and that is the day I’m working towards.”

The silence around sexual violence in the humanitarian aid community is linked to other forms of institutional silence of internal sexual violence. Each time, women are told in so many ways that they are collateral damage of a righteous and noble cause, and that, as Megan Norbert put it, they must just “suck it up.” They should have known to expect something like this. That’s humanitarian logic.

When Sarah Pierce and Megan Nobert were told to shut up, they replied, “NO!” Instead they opted to put an end to survivor “bravery” and work to create spaces in which “humanitarian” and “rape” can never again be conjoined, for any reason.

(Photo Credit: JC McIlwaine/ United Nations)