On Tuesday, October 19, 2021, the Justice Committee of the United Kingdom’s Parliament took “evidence on safety and wellbeing of women in prison” … or the absolute, radical and contrived absence thereof. Among the witnesses were Sandra Fieldhouse, Inspector, Leader of the Women’s Inspection Team, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons; and Juliet Lyon, Chair of the Independent Advisory Panel on Deaths in Custody. Juliet Lyon introduced the “Justice” Committee to the practice of gate sectioning: “The other thing that has arisen that I want to put down a marker about, which I think is mostly anecdotal, although I am sure it is happening, is what is called people being held at the gate, and then put under the Mental Health Act—and then the gate sectioning, which is the way it is referred to. There have been a number of incidents, particularly in relation to women, where they thought they were leaving—they were literally at the gate—and they have to be through that gate before it can happen: they are sectioned, taken away and put in secure care. That simply cannot be right. It is a very cruel thing to do, and it indicates that prison has been allowed to hold on to someone whose behaviour and health have been very poor, and they have been very damaged by it. Gate sectioning is occurring more readily …. It has got to be stopped. It is just not the right way to proceed at all.”

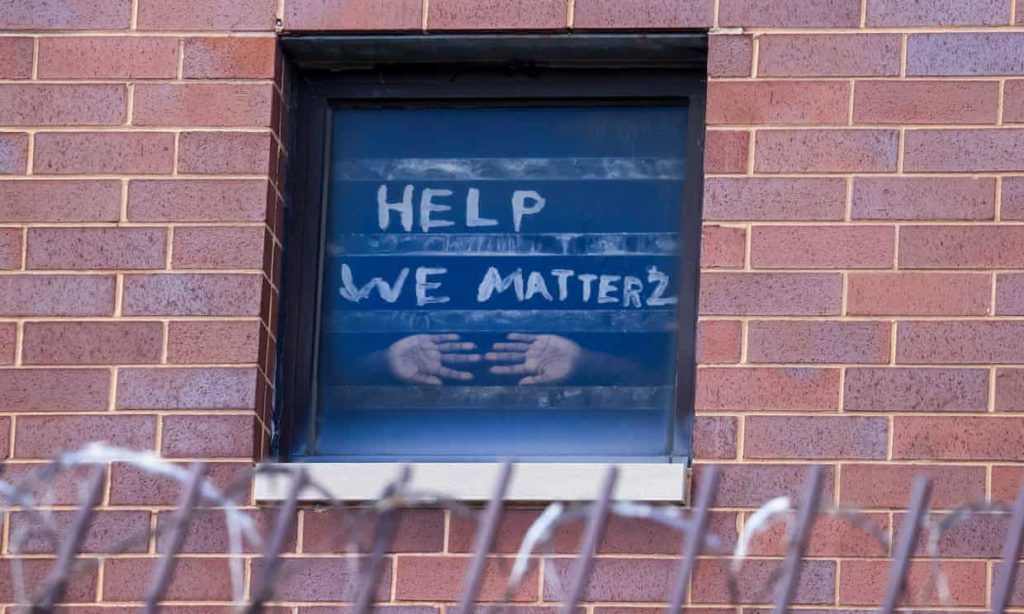

It has got to be stopped. It also has to be asked why it happens at all. Prison officials claim that the main reason is that there aren’t enough spaces in mental health facilities … and so they wait until the last moment, actually the moment after the last moment? To be clear, and one must visualize this, women who have been in poor health, often before prison and more often than not intensified by their stay in prison, even brief stays, are told, “Today, your term is up. You are free to leave.” They pack their belongings, say goodbye to their sisters inside, and head for the exit. Once they have taken a step beyond the exit, they are taken off. This is not about lack of resources. Somehow, magically, when women are released from prison, the beds appear. This is about cruelty, pure and simple.

It isn’t as if leaving prison, going through the gates, is easy for women. As Carolyn Harris, MP for Swansea East, noted earlier this year, “Over half of all women leaving prison have nowhere safe to go. They walk through the gate with three things: the paltry £46 prison discharge grant, a plastic bag full of belongings, and the threat of recall if they miss their probation appointment. For some, the simple fact that they have been in prison a long way from home means that they have no local connections when they are released. For others, who are victims of abuse, returning to their homes, and consequently the perpetrators, comes at a huge personal risk.”

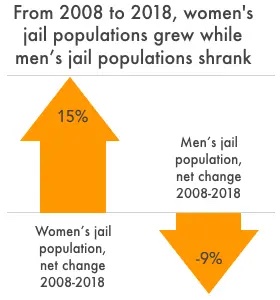

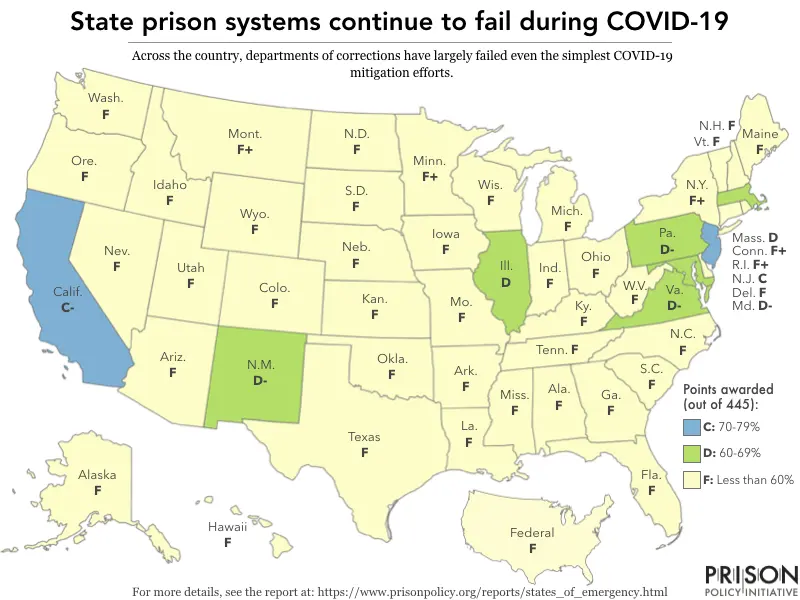

In 2015, the English government established the Through the Gate program, which was supposed to address the issue of people moving back into the community. At that point, the services were poor to nonexistent. In 2017, an evaluation was published that found that people leaving after longer sentences were not prepared for release. In 2016, an evaluation found that people leaving after shorter sentences were not prepared for release. Both evaluations acknowledged the greater incidence of mental health issues among incarcerated women, especially PTSD. That was five years ago, and today … women are snatched at the gates and `sectioned’ off. Meanwhile, a report to Parliament on mental health in prison, submitted September 21, 2021, found “71% of women and 47% of men surveyed by inspectors in prison self-reported having mental health problems.”

Two years ago, the Governor of Low Newton prison is reported to have said, “We wouldn’t ask someone with a broken leg to hobble around waiting until release for treatment”. We wouldn’t, but we do. In which circle of hell does gate sectioning appear?

(By Dan Moshenberg)

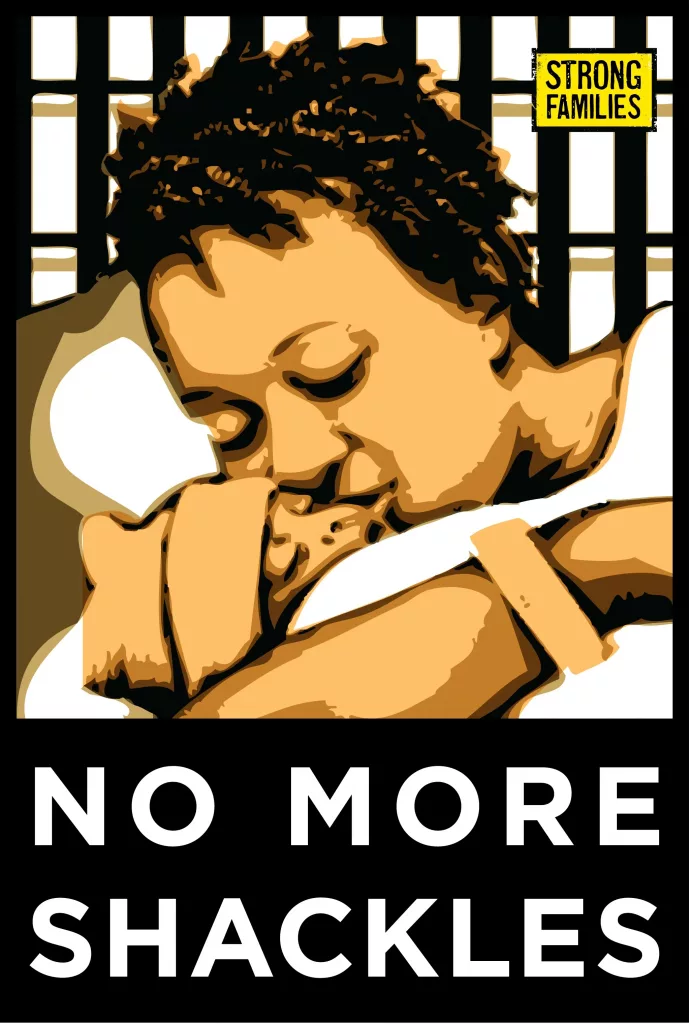

(Image Credit: Grace Wilson / Vice)