On August 17, the Queensland Sentencing Advisory Council issued a report, Engendering justice – the sentencing of women and girls, that found, yet again, that, from 2015 to 2019, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in Queensland were disproportionately subjected to incarceration, usually for `minor offences’, usually for short less than a year periods. This happened despite numerous national, organization, and academic reports and recommendations that clearly stated that incarceration for low level offenses was bad for everyone and that short term imprisonment was deeply damaging. And yet here we are, with a skyrocketing rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women seemingly trapped behind bars.

That report follows a Guardian Australia report the week before that over 1200 people are detained without having been convicted, sometimes for decades. How? Most of the 1200+ are individuals who were deemed unfit to plead after being charged or were found not guilty due to mental impairment. So, `for their own protection”, they were thrown into prison. In the Northern Territory, one person has been in the Darwin Correctional Centre for more than 30 years. For their own good.

In 2018, Victorian Ombudsperson Deborah Glass investigated the 18-month imprisonment of a 39-year-old woman found unfit to stand trial and not guilty because of mental impairment. And so the province dumped her in solitary. Again, why? Because “Victoria has no secure therapeutic facilities for women with Rebecca’s disability. Authorities were concerned about releasing her into the community because she had no housing or services.” Nowhere to go? Go to jail, to solitary. As Deborah Glass noted, “We heard many more stories, some as sad as Rebecca’s, of people with significant disabilities who had spent long periods in prison. These stories highlight both the trauma of incarceration on acutely vulnerable people, and the threat to community safety in failing to provide a safe and therapeutic alternative to prison.” Glass concluded this case was “the saddest case I have investigated in my time as Ombudsman”.

In response to this week’s report on Queensland, Debbie Kilroy, founder of Sisters Inside, noted, “The thing with these reports and recommendations … the recommendations are not implemented. We’ve even got recommendations from the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody from 1991 to decriminalise and repeal public drunkenness, and that still hasn’t happened. Governments continue to fund inquiries and reports, but recommendations continue to sit on the bookshelf, gathering dust for decades and decades and decades.”

The recommendations gather dust, the infirm sit in solitary, we hear many stories, sadness abounds. Over four years ago, Australia signed international treaties that required it to open its prisons to independent oversight. Thus far, it has successfully delayed any visit. Signing the document was the point, not changing the system. Debbie Kilroy understands this cynicism and the way in which it abuses language. When a bill was introduced this week to raise the age of criminality to 14, Debbie Kilroy replied, “So what you’re saying is a child, an Aboriginal girl that’s 14 years and one week old, can actually be put in a cage. I do not agree with that — no child should be caged ever.” Start there. No child should be caged ever, no vulnerable person should be caged ever, no person or persons should be caged ever. Ever.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

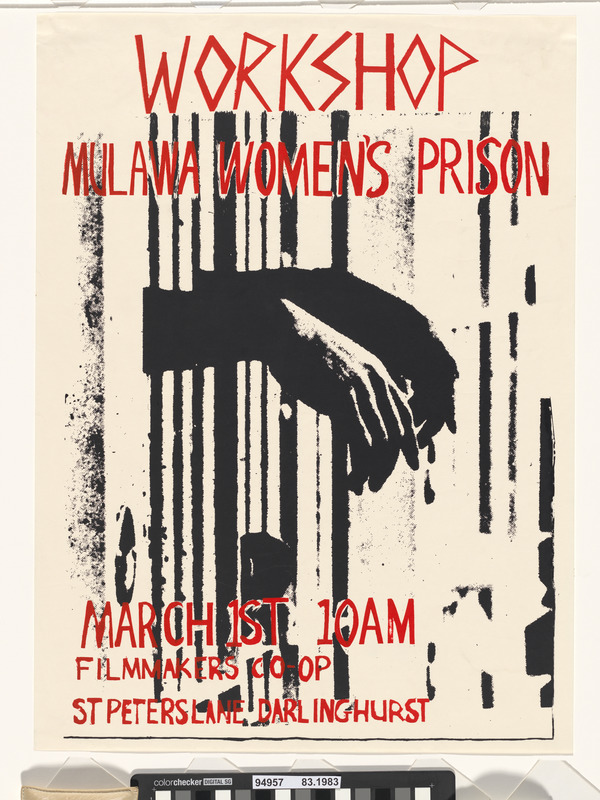

(Image Credit: National Gallery of Australia)

A cell in Brisbane’s Wonen’s Correctional Centre

A cell in Brisbane’s Wonen’s Correctional Centre