What does freedom mean? Don’t ask the Australian government, who this weekend hit a new low by proudly announcing it had released all refugee and asylum seeking children in Australia, when, apparently, it had merely changed their designation from “held detention” to “community detention”, without actually moving them. When torturing children just isn’t enough, try torturing the language as well. Freedom’s just another word …

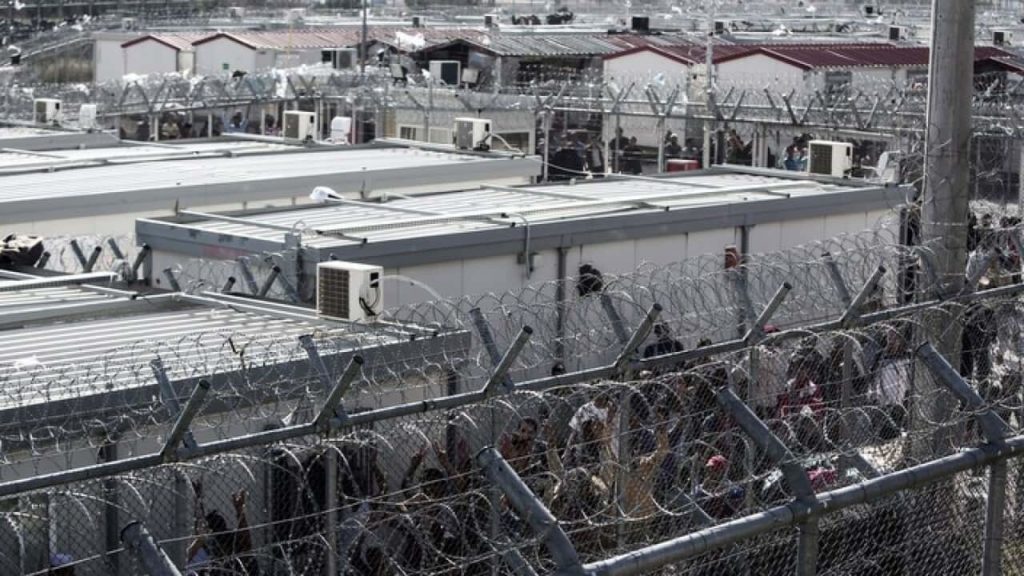

Years ago, Australia’s government looked out upon the waters, saw small boats filled with desperate people, declared them a crisis and installed a state of emergency. The State has tried everything, from detention and torture to offshore detention and torture to way offshore detention and torture, from places like Villawood Immigration Detention Centre to Nauru Regional Processing Centre to who knows what or where in Cambodia. The landscape is littered with rising piles of bodies, commission reports, and expressions of shock at the routine torture of women, children, and men. Lately increasing numbers of Australians have protested in favor of a more open policy, under the banner #LetThemStay. And so, over the weekend, the State tried a new sleight of hand, and declared the war is over, even though the fighting actually continues.

When challenged on the terms of “release”, Australia’s Immigration Minister explained, “We’ve been able to make a modification to the arrangement so the children aren’t detained, they can have friends over, they can go out into the community.” Pushed by reporters, he further explained, “The same definitions apply today as they did before. There are certain characteristics that need to be met in relation to all these definitions, but that’s all beltway stuff. They’re outside of ‘held detention’, so that’s the answer that I’ve provided to you before.” Still unsatisfied with the release that is not a release, reporters continued to seek clarification, and a spokesperson for the Minister complied, “There are arrangements that have been put in place. Those arrangements now sit with the fact that it’s community detention.” That kind of obfuscation is “stuff” that beltways are made of.

Here’s the situation in plain words: “Families with children in `held detention’ in the `family compound’ of Villawood detention centre were told by letter on Friday that their detention was now classified as `community detention’. They have been `released’ from detention without moving.”

On Saturday night, a nineteen-year-old woman attempted suicide. Others will follow. Today Australia’s Immigration Minister vowed to ship the families to Nauru … and beyond. The bodies pile up, the lies grow more intricate and more brazen, the shame deepens, and people and words are made to disappear. Soon, if all goes according to plan, no one will care about words like democracy, freedom, decency, or humanity.

(Photo Credit: The Guardian / Pacific Press / REX / Shutterstock)