Afghanistan, where life is a cruel race with death. On Wednesday an ISIS suicide bomber walked into an education centre for the national university entrance exam and detonated his bomb belt killing over 40 students in their teens and early 20s. This attack came amid an accelerating spate of violence following the four-day siege of the Ghazni province which resulted in the death of hundreds of civilians and Afghan armed forces. Over 10,000 civilians were killed or injured only in 2017, hundreds of whom were killed in the capital, Kabul. Afghans live in a state of perpetual mourning young lives , dreams that are crushed and smiles that perished forever, with a question lingering in the back of our minds, “Who should we mourn first, yesterday’s victims, today’s or tomorrow’s?”. Yet these people maintain their resilience and strive for a better future while there is no clear end to the war in sight.

Afghans know that a sustainable peace process in Afghanistan depends on overcoming not just one but many formidable hurdles, including the Taliban and the so-called ISIS-Khorasan Province; and the perpetual direct and indirect interference of neighbouring and regional countries: Iran’s subversion, Pakistan and India’s conflict; the US, Russia and China’s influence and ambitions in the region and the list can go on. For now the prospects of peace in Afghanistan remain grim, it has been for the past 40 years and the war is unlikely to abate anytime soon.

However, in the face of it all, the honour and resilience of the Afghan people requires wide acknowledgement and is a source of inspiration. While students are constantly held in the crossfire of war; and extremist groups threaten to wipe out the future of a generation of millions of children; many families still prioritize education. According to the War Child, education helps families in stressful war circumstances give their children a “sense of normality and improves the prospects of recovery and longer-term wellbeing.” In recent years many Afghan youths have been actively participating in book clubs, academic conferences, social discourses and have created an open culture of criticism and free expression within their communities and on social media. However, this has come at a price of losing lives and loved ones.

In the aftermath of the attack on the education centre, as usual reactions of sorrow, anger and call for justice poured in the social media by Afghans all over the world. Photographs of the scene were widely circulated on the social media, depicting the rubble, the bloodied floor, tattered notebooks and textbooks, shattered windows, broken desks and chairs, and body parts. These photographs accompanied mournful statements and a call of solidarity and encouragement for the youth to continue education. In the obituary of one of the victims, Madina Lali, the family wrote, “No one can derail us from our pursuit of education. If you martyr one of our students, we extend a hand to 5 more and enter schools and universities. Once more we will rise from blood and ashes and will salute wisdom and knowledge. No one can eliminate us.”

Moreover, stabilization of a fragile state like Afghanistan also requires a comprehensive approach to ensure justice. It is not enough to respond to the Taliban and the ISIS who are implicated in the killings of thousands of civilians, just by military action. They always rise again and in more numbers than before. In order to kill the concept and ideology of these terrorist groups; their brutality and corruption need to be exposed and brought to justice.

Since November 2017 till January 2018, thousands of Afghans civilians and journalists have filed complaints with the International Criminal Court of Justice (ICC) against the extremist groupssuch as the Taliban, the Afghan National Security Forces, and the U.S.-led forces. The ICC prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda says there is a “reasonable basis to believe” that war crimes and crimes against humanity in Afghanistan have been committed by all sides and asked for authorization from a pre-trial chamber of judges to fully investigate. The people behind these atrocities need to face their crimes in the court of justice and not be given impunity in the course of any peace negotiations.

Afghans are in perpetual mourning of the daily loss of lives. We start our days with a dose of news of yesterday’s casualties of war and end our nights counting today’s casualties; all the time wondering which friend or family was among them. And yet we have maintained our resilience and strive for better tomorrows even though there is no end in sight for the current war. “We will rise from blood and ashes and salute wisdom and knowledge.”

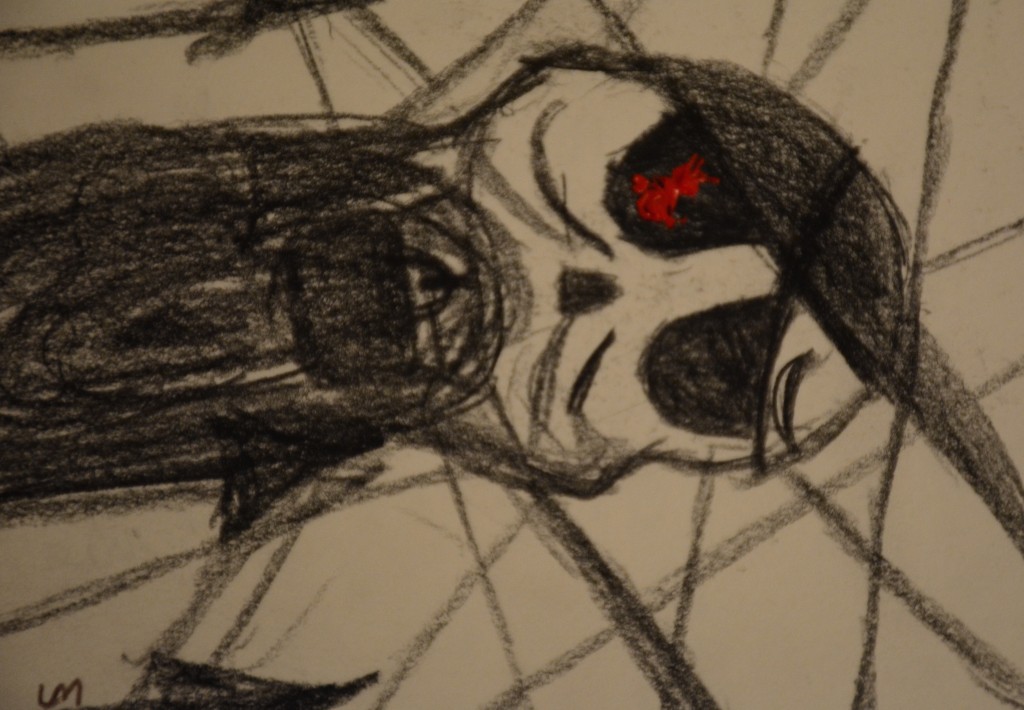

(Photo provided by author)