The entire point of organizing and direct action is to confront people and power, disrupting their everyday lives-or their paths of least resistance-to make sure to hold those people accountable and to reclaim power of those who normally feel powerless. So, when there is consistent criticism of an immigration activist who followed Senator Sinema into the bathroom of ASU, I am fascinated to ask what organizing and disrupting state power means to those who are voicing that criticism?

Is it not an act of violence and dismissiveness when Sinema, using her position as a Senator of the United States Congress, dramatically girl-bossed her rejection of raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour? A provision that would have lifted millions in this country out of poverty.

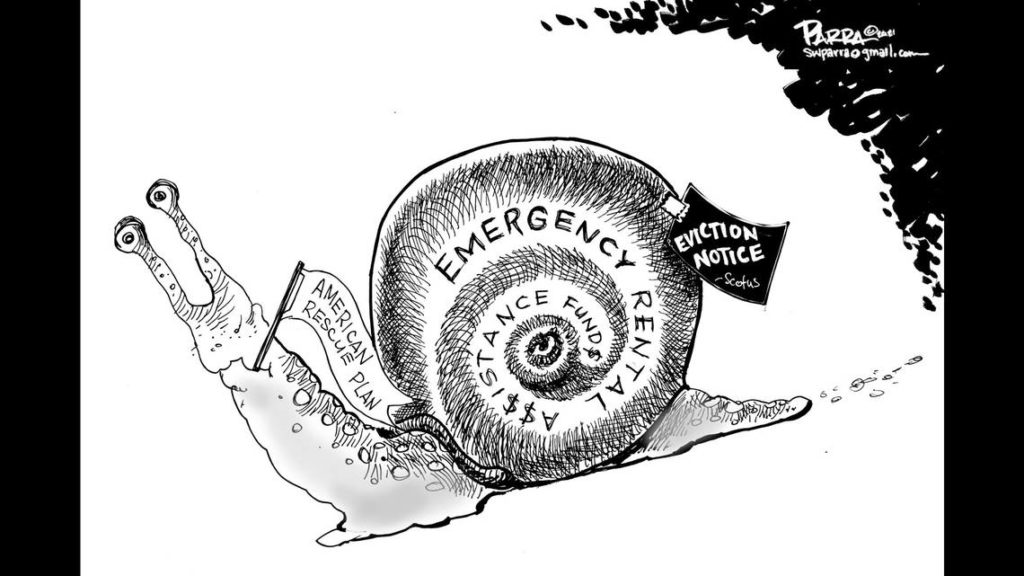

It is not violence, worthy of a faceoff in the bathroom, on an airport, in a airplane, when Sinema rejected an infrastructuredeal agreed upon in August, demanding a smaller bill from $3.5 trillion to $1 trillion, erasing the potential for universal childcare, free community college, and investing in cleaner energies that would combat a disastrous climate crisis?

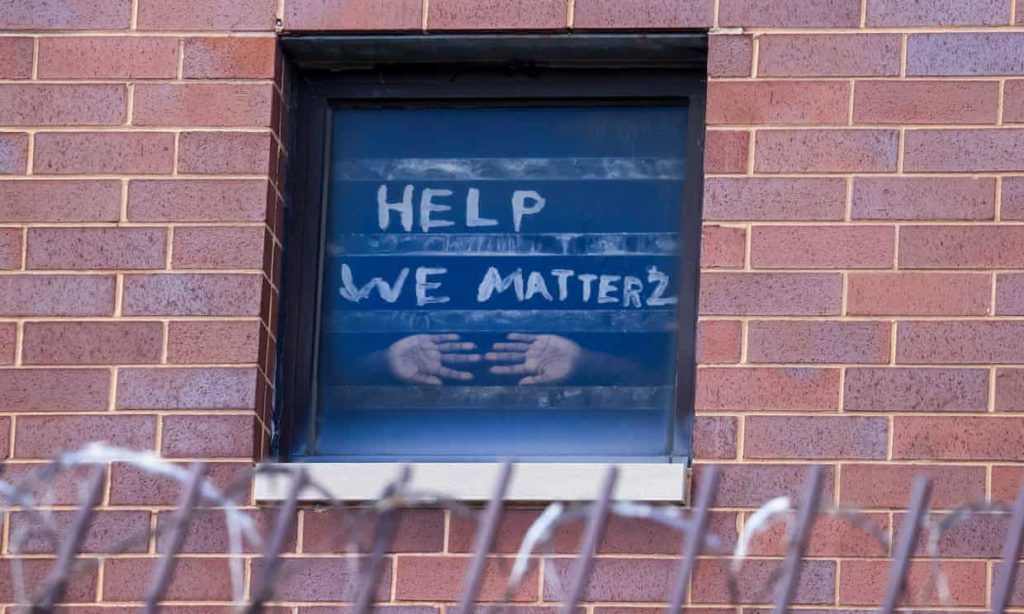

Then if it is, what does it matter if Sinema is asked some questions about her vote, in the only places that constituents can get to her? She hasn’t had a town hall in three years! So what if they get her at a university-where she ran away from them into a bathroom stall. So what if they catch her at the gate of an airport? Is she doing any outreach herself?

But it’s inappropriate!

So is delaying a bill that has the potential to help people.

But you wouldn’t want to be accosted in the bathroom!

Goodness I hope not. That would mean I’m a terrible politician that would deny her constituents the means to be uplifted out of poverty, comprehension immigration reform, and cleaner infrastructure. And I’m not Kyrsten Sinema, who is doing just that.

But you need to be polite! This distracts from your goal of getting the bill passed!

This is exactly what activists should be doing. Disrupting a person’s path of least resistance. If those students and activists did nothing, then she would have easily gone back to Arizona and spent the entire time fundraising and thinking it was ok. This is putting her shady habits into the spotlight. Why the hell are activists blocking traffic? Or occupying spaces? It’s so those in power don’t ignore them. Which politicians have a surprising habit of doing.

Sinema should be prepared for more questions in inconvenient places. So should Manchin too, while we’re at it, because it seems a little too spot on the nose that he is lecturing about fiscal responsibility atop his yacht.

You can’t respectability politics your way out of this one.

(By Nichole Smith)

(Photo Credit: NY Post / Twitter)