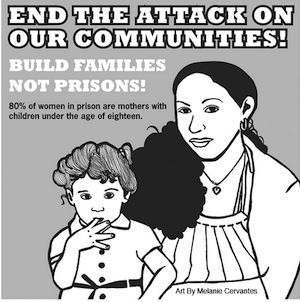

Last week, domestic workers declared war on the War on Women.

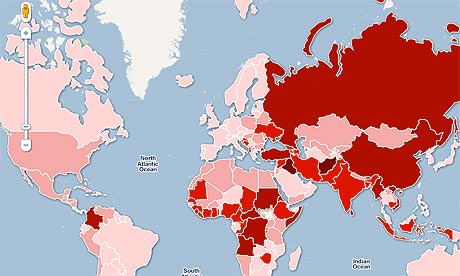

The current domestic laborers’ market has been forged in the most recent phase of globalization – understood, too briefly, as the political economy of globalized production serving a global market – that began in the 1970s. The last four decades have been marked by the rise of global cities, and mega-slums. Already, more than half the world population is urban. Soon, very soon, more than half the world population will live in slums. A planet of slums beckons.

Cities are the place, and slums are the face of urban poverty in the new millennium. And that face is a woman’s face “Women bear the brunt of problems associated with slum life.”

Global cities produce mega-slums and slum cities. Meanwhile, global cities’ 25-hour-a-day, 8-day-a-week so-called service economies require large numbers of easily available, and replaceable, and cheap domestic workers who make sure the beds are made; the food prepared and tasty; the children and the elders cared for; the houses swept; and the structures of household, community, regional, national and global patriarchy solidified and intensified. Political economists tell us that the new economies produced social workers, workers in the information sector whose work is more than and different from the binary of boss and worker. Tell that to the maids and nannies, childcare and eldercare providers (as well as the hotel and office cleaners, and sex workers) across the globe who every day, and every night, make sure everything is neat, tidy and available. It’s a world economy in which women, especially women of color, are forced to care.

In order to meet this demand, nation-States, the Philippines most notably, have turned themselves inside out and, presto, turned into mega-brokerage houses for mass migrations of domestic workers. Global cities demanded, and created, transnational domestic labor, which became one of the fastest growing, and largest, labor sectors of the world economy.

Women workers built the global economy, which came to rely, violently, on women workers. The feminization of the new industrial workforce produced the feminization of migration, which in turn produced the feminization of survival, and all of it, the whole system, sits heavily, and precariously, on the shoulders and in the arms of domestic workers.

That is one reason that the ILO Convention Concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers, passed last week, is called a landmark treaty, a milestone. Here is a key section from that document:

“Considering that domestic work continues to be undervalued and invisible and is mainly carried out by women and girls, many of whom are migrants or members of disadvantaged communities and who are particularly vulnerable to discrimination in respect of conditions of employment and of work, and to other abuses of human rights, and

Considering also that in developing countries with historically scarce opportunities for formal employment, domestic workers constitute a significant proportion of the national workforce and remain among the most marginalized …

Recognizing the special conditions under which domestic work is carried out that make it desirable to supplement the general standards with standards specific to domestic workers so as to enable them to enjoy their rights fully.”

Women and girls are “the special conditions under which domestic work is carried out.”

“Special conditions”.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, W.E.B Du Bois famously noted “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” For Du Bois the color line came down to a simple, and impossible, question: “How does it feel to be a problem?” Today, the problem of the Twenty First Century continues to be the problem of the color line, and the question now is, “How does it feel to be a special condition?”

Domestic workers around the world, and in our neighborhoods, recognize that question as part of a global War on Women, and they have had enough. Domestic workers refuse to be ghosts in the machinery of “special conditions.” They have declared war on the War on Women. Step up, step up, it’s not too late to enlist.

(Photo Credit: David Swanson / IRIN / The New Humanitarian)