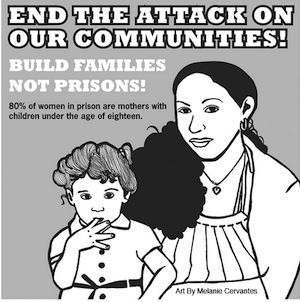

Mary Ann Allas and Baby Jane Allas

In 2014, former domestic worker Erwiana Sulistyaningsih stood before a gathering of women and gave witness to the horrors she had endured: “My name is Erwiana Sulistyaningsih. I am 23 years old, and come from a poor peasant family of Indonesia and am a former domestic worker from Hong Kong … I chose Hong Kong because it is said to be a safe country and I had heard no news about migrant workers being abused there.” Hong Kong was not, is not, safe. Over the last month a number of women domestic workers’ stories have emerged that demonstrate both the spectacular brutality of households and the structural brutality of nation-State. These are the stories of Baby Jane Allas, Moe Moe Than, Milagros Tecson Comilang, Desiree Rante Luis.

Baby Jane Allas arrived in Hong Kong in late 2017. She left behind five children. In early 2019, Baby Jane Allas was diagnosed with third-stage cervical cancer. She took medical leave, as is her right under Hong Kong law. On February 17, while on leave, she received a letter from her employers terminating her contract. Along with the loss of job, this also meant loss of access to public medical care. That letter was a slow death sentence. Baby Jane Allas, and her sister Mary Ann Allas, also a domestic worker in Hong Kong, organized. They raised money for medical care. They sued, under both labor law and disability laws. The case is still ongoing, but supporters already note that there were many `irregularities’ in the hearing. Baby Jane Allas reported that her stay of employment was one abuse and violation of law and rights after another, but she needed the job. She’s a single mother of five children.

Moe Moe Than’s story is one of spectacular cruelty, the “worst of its kind”, according to a judge. 32-year-old Moe Moe Than arrived in Singapore from Myanmar in 2012. She worked for a couple that refused her food, access to the toilet, time off and worse. At one point, when complained about the quality and quantity of food, the couple forced fed Moe Moe Than, and when she vomited, the forced her to eat her vomit. Her employers beat her regularly and forced her to clean in her underwear. All of that occurred in 2012. In March, seven years later, the couple was sentenced to time in prison and to compensation. This same couple was convicted of abusing an Indonesian maid, in 2017, and never served any time in prison.

Finally, there are the cases of Milagros Tecson Comilang and Desiree Rante Luis, both former domestic workers from the Philippines. Milagros Tecson Comilang arrived in Hong Kong in 1997. In 2005, she married a permanent Hong Kong resident. In 2007, she gave birth to a daughter. Comilang and her husband have since divorced, and he refused to support her application to stay. Desiree Rante Luis arrived in Hong Kong in 1991. She has three sons, all permanent Hong Kong residents, but Desiree Rante Luis had to leave, and has only seen her family while on a tourist visa. She also applied for permanent residence status. In the case of Milagros Tecson Comilang the child’s father doesn’t want to care for his child. In the case of Desiree Rante Luis, the father is a live-in domestic worker, and so can’t care for his children. This week, the court decided that both women have to leave Hong Kong and leave their children behind. Desiree Rante Luis said, “We have been waiting for a long time. I don’t know why the Hong Kong government has no heart.”

Why do the Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and so many other, governments have no heart for transnational women? It’s a good question. Here’s another good question: “Each page a victory/At whose expense the victory ball?” Bertolt Brecht asked that in 1936. It’s now 2019, 83 years later. Baby Jane Allas, Moe Moe Than, Milagros Tecson Comilang, and Desiree Rante Luis join Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, Adelina Lisao, Tuti Tursilawati, and so many others whose names we wait to learn. We need more than an archaeology of contemporary household atrocities. We need justice. We need justice which begins at home. We have been waiting for a long time.

Desiree Rante Luis and her sons

(Photo Credit 1: South China Morning Post / Xiaomei Chen) (Photo Credit 2: South China Morning Post / Edmond So)